A new study shows how IL-2’s flexible structure governs its effects on the immune system, providing crucial information for harnessing its therapeutic potential

Credit: Viviane De Paula

The signaling molecule interleukin-2 (IL-2) has long been known to have powerful effects on the immune system, but efforts to harness it for therapeutic purposes have been hampered by serious side effects. Now researchers have worked out the details of IL-2’s complex interactions with receptor molecules on immune cells, providing a blueprint for the development of more targeted therapies for treating cancer or autoimmune diseases.

IL-2 acts as a growth factor to stimulate the expansion of T cell populations during an immune response. Different types of T cells play different roles, and IL-2 can stimulate both effector T cells, which lead the immune system’s attack on specific antigens, and regulatory T cells, which serve to rein in the immune system after the threat is gone.

“IL-2 can act as either a throttle or a brake on the immune response in different contexts,” said Nikolaos Sgourakis, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at UC Santa Cruz. “Our investigation used detailed biophysical methods to show how it does this.”

Sgourakis is a corresponding author of the new study, published March 17 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. First author Viviane De Paula, a visiting scientist in his lab from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, used nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) to observe IL-2’s structural dynamics. The study was done in close collaboration with corresponding author Christopher Garcia’s group at Stanford University.

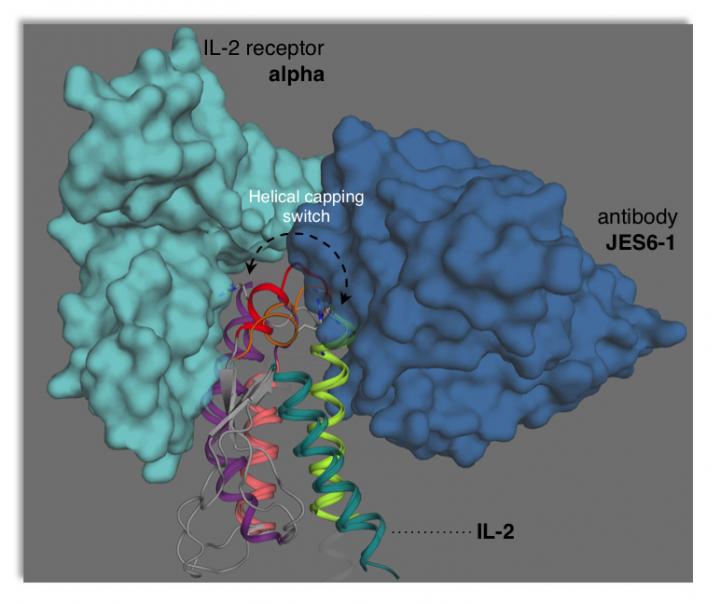

The researchers were able to show that IL-2 adopts two different structural forms (termed conformations) that affect how it interacts with the receptors on different types of T cells. In solution, IL-2 naturally shifts back and forth between a minor conformation and a major conformation. The study also showed how certain mutations or interactions with other molecules can bias IL-2 toward adopting one conformation or the other.

“We have now come one step closer to a detailed understanding of how the IL-2 cytokine works,” de Paula said. “It is the first time that anyone has managed to observe a transient state of IL-2 directly. With the use of NMR, we were able to describe the structure, dynamics, and function of IL-2 in its two conformations.”

The study opens up numerous possibilities for designing drugs to stabilize IL-2 in a particular conformation for therapeutic applications.

“We can use this information to tweak the balance, depending on what we want to achieve in a clinical setting,” Sgourakis said. “To target regulatory T cells, we would want to stabilize the minor conformation, and to target effector T cells, we would want to stabilize the major conformation.”

Previous efforts by other researchers had already shown that different monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-2 could promote the expansion of different T cell populations in mice. One of these antibodies in complex with IL-2 was effective in treating mouse models of autoimmune disease and inflammation. And a similar human monoclonal antibody is currently heading toward clinical trials for the treatment of autoimmune diseases.

The new study provides a mechanistic explanation for these effects that can guide further drug discovery efforts.

“The details of the mechanism we present offer a direct blueprint for drug discovery,” said Garcia. “Every drug company wants to know how to engineer this cytokine, and this paper provides some of the first really bona fide structural clarity on the fascinating topic of IL-2 dynamics.”

###

In addition to De Paula, Garcia, and Sgourakis, the coauthors include Kevin Jude and Caleb Glassman at Stanford and Santrupti Nerli at UC Santa Cruz. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Media Contact

Tim Stephens

[email protected]

831-459-4352

Related Journal Article

http://dx.