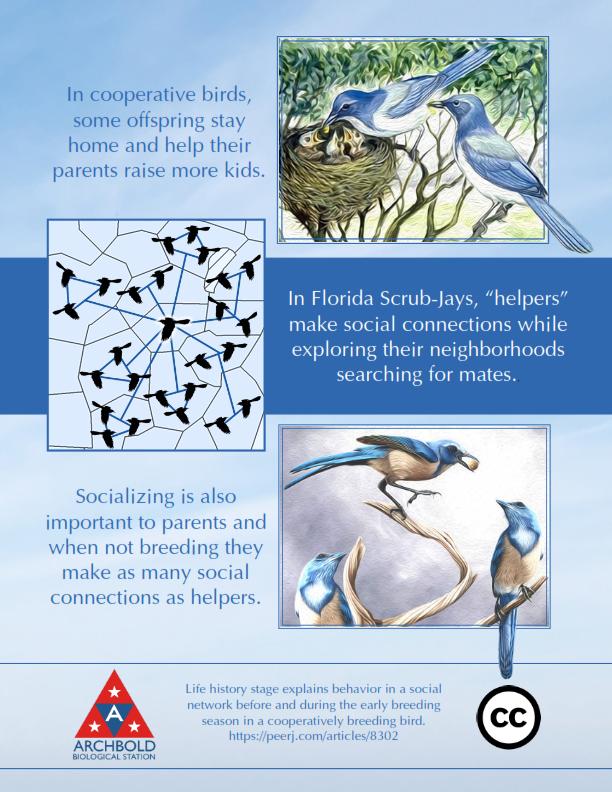

Life history stage explains behavior in a social network before & during the early breeding season

Credit: Archbold Biological Station

There are numerous articles on how friendships change in your 20s, 30s, and after marriage or parenthood. What we don’t know is how ubiquitous these changes are throughout the animal kingdom. Researchers from Archbold Biological Station describe the social lives of Florida Scrub-Jays in different stages of life in the journal PeerJ on February 10, 2020.

Florida Scrub-Jays are monogamous cooperative breeders that mate for life. In most birds, after the offspring leave the nest they disperse to breed on their own. In Florida Scrub-Jays, the young delay dispersal, remaining with their parents to help rear their younger siblings for the next few years. They are known as helpers.

Lead author Dr. Angela Tringali, along with co-authors that included two post-baccalaureate research interns, found that these helpers associate with many more individuals than breeders. “If helpers want to become breeders, they need their own territory and mate. In addition to helping their parents, they make forays away from home, presumably looking for available territories and potential mates. This increases the number of other birds that helpers associate with and the helpers’ importance in connecting individuals with one another,” explains Tringali. Whether a bird was a breeder or helper explained 38% of the variation in the number of individual “associates” among birds and 48% of its ‘cliquishness’, the tendency to associate with a set of individuals all of whom are directly associated.

In 2018, a year marked by unusually low reproductive success at Archbold, where the demography of Florida Scrub-Jays has been studied for 50 years, some breeders did not nest, and those that did nest began later in the year. In this year, breeders socialized with far more birds, much like the helpers. Without nests or young that needed care, breeders chose to interact with other individuals outside of their immediate family, in a manner similar to helpers, suggesting that social interactions are more important than simply finding a new mate.

The authors conclude that an individual’s strategy for success changes with its life stage. As helpers, individuals explore to find a territory and mate, but once found, the priority shifts to defending their territory and provisioning offspring. But even for breeders, when time permits, socialization beyond the family group is important. “We have tended to frame foray behavior strictly as a strategy for finding a territory or mate, but this analysis demonstrates that when not tending an active nest, breeders also will foray beyond their territories. Maintaining extra-group relationships may reduce the costs of territory defense, predation risk, or the time spent in vigilance, and enhance knowledge of the status of neighboring territories,” noted Dr. Reed Bowman, Research Director of the Avian Ecology Program at Archbold Biological Station.

The authors note that these conclusions are based on ‘snapshots in time’ collected by scientists visiting sampling points near the intersection of scrub-jay territory boundaries twice per week. Next, the plan is to get a more complete picture of where, when, and with whom the birds are interacting. Dr. Bowman says, “We are completing a pilot project tracking scrub-jays tagged with a new technology of transmitters whose signals are received by a grid of receivers. We will know the exact location of multiple scrub-jays throughout the day, which will enable us to answer questions about social interactions in more detail and better understand habitat use, movement, and dispersal.”

###

Media Contact

Deborah Pollard

[email protected]

863-465-2571

Related Journal Article

http://dx.