Researchers uncover patterns of gene expression within sea grapes

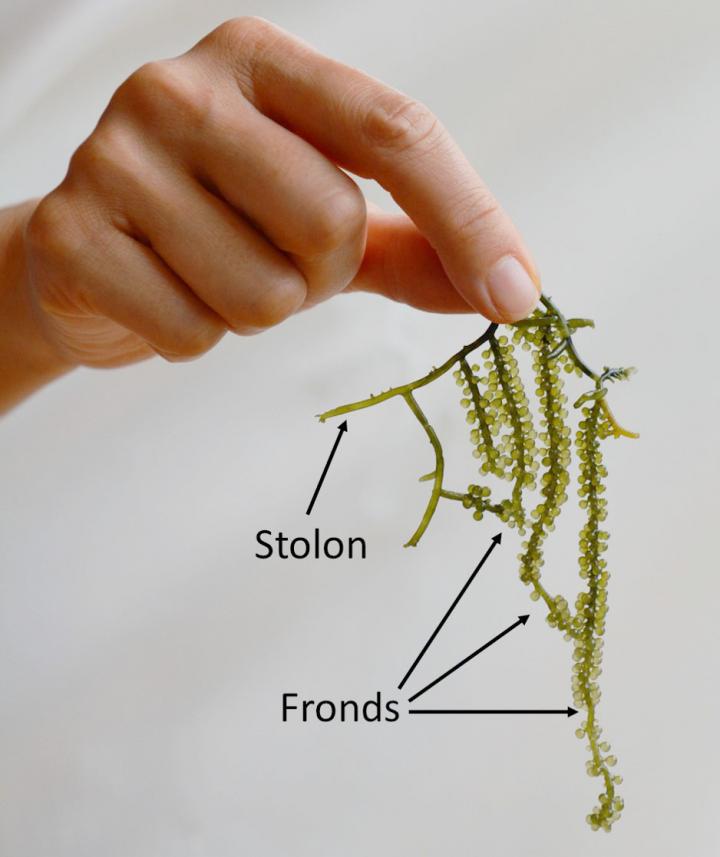

Credit: OIST Graduate University

Okinawan cuisine is known for its many delicacies – from squid ink soup to rafute pork belly. But one of the most famous delicacies served in restaurants across Okinawa is a type of seaweed, which is renowned for its pleasing texture and taste. Instead of leaves, this seaweed has bundles of little green bubbles that burst in the mouth, releasing the salty-sweet flavor of the ocean.

The unique shape of this bubbly algae gives it the name “umi-budo” or “sea grapes”. Umi-budo is a staple crop in Okinawa which is cultivated for market by the fishery industry. Researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) recently unveiled key information about gene expression in sea grapes, which could help shed light on the evolution of sea grape morphology and help Okinawan farmers improve cultivation of umi-budo.

“Sea grapes are composed of two main structures – the fronds and stolons, which are similar to plant leaves and stems. The shape of umi-budo is very interesting because the whole seaweed, which can grow fronds of up to 30cm in length, is composed of just one single cell with multiple nuclei,” said Dr Asuka Arimoto, first author of the study and a postdoctoral scholar previously working in the OIST Marine Genomics Unit, which is led by Professor Noriyuki Satoh. “Our research showed that despite being one cell with no physical barriers, there were differences in gene expression between the fronds and stolons, which was very unexpected.” The team believes that investigation into these differences can illuminate the function and development of the fronds and stolons.

The study, which was recently published in the journal Development, Growth and Differentiation on November 11th, 2019, used sea grapes cultivated at Onna Village Fisheries Cooperative, located only a few kilometers from the OIST campus. The scientists extracted and sequenced mRNA – a molecule which carries information from expressed genes into the jelly-like liquid of the cytoplasm, where it is used to code for proteins. The team then calculated the levels of gene expression in the two different structures. Earlier this year, the OIST Marine Genomics Unit decoded the sea grape genome and estimated the presence of 9,311 protein-coding genes in the genome. In this latest research, the scientists found that out of the 9,311 genes, 1,027 genes were more highly expressed in the fronds, whereas 1,129 genes were more highly expressed in the stolons.

Exploring the similarities between sea grapes and land plants

One major advantage of this study was the ability to utilize past research from the OIST Marine Genomics Unit, which had not only previously decoded the genome of sea grapes but had also compared the sea grape genes with other land plants.

“Having genomic information to base our gene expression analysis on was incredibly useful, as it allowed us to more easily identify which genes were more highly expressed, and to characterize genes by their function,” said Arimoto.

The team found that genes involved in metabolic functions such as respiration and photosynthesis were more highly expressed in the fronds, whereas genes related to DNA replication and protein synthesis were more highly expressed in the stolons. These results showed that sea grape fronds have a similar function to the leaves of land plants.

The researchers also delved further into a group of genes that regulate plant hormone pathways, which was shown in the previous study to be expanded in sea grapes compared to land plants. The results showed that a larger variety of plant hormone genes were expressed in the fronds, compared to the stolons.

“The plant hormone pathways help control the development of sea grapes and keep conditions within the seaweed stable,” said Arimoto. “What is extraordinary is that despite land plants and green seaweed diverging a billion years ago, we have found that they have independently evolved similar mechanisms for regulation and development.” Arimoto therefore thinks that exploring the biology of unconventional unicellular organisms, such as sea grapes, could also help scientists uncover the common principles of development and evolution among various plant and algal species.

Helping Okinawan farmers cultivate umi-budo

As well as shedding light on algae and land plant evolution, Arimoto believes that this information could lead to better methods of increasing frond growth, allowing Okinawan farmers to cultivate a more productive crop. “The fronds are the edible part of sea grapes, but it can be difficult for Okinawan farmers to cultivate sea grapes with fronds that have many bubbles without advanced scientific techniques,” said Arimoto.

The Marine Genomics Unit also hopes that in the future, their science can help Okinawan farmers to cultivate umi-budo with greater tolerance to drought, high temperature or more extreme salinity. One of the plant hormone pathways – known as the abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathway – plays a role in allowing the seaweed to cope with environmental stress. Further research into this pathway could help farmers in Okinawa and other regions to deal with the rapidly changing climate.

###

Media Contact

Tomomi Okubo

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.