Credit: Illustration is courtesy of the Max Planck Society

Washington, DC– The discovery of a 13 billion-year-old cosmic cloud of gas enabled a team of Carnegie astronomers to perform the earliest-ever measurement of how the universe was enriched with a diversity of chemical elements. Their findings reveal that the first generation of stars formed more quickly than previously thought. The research, led by recent Carnegie-Princeton fellow Eduardo Bañados and including the Carnegie’s Michael Rauch and Tom Cooper, is published by the Astrophysical Journal.

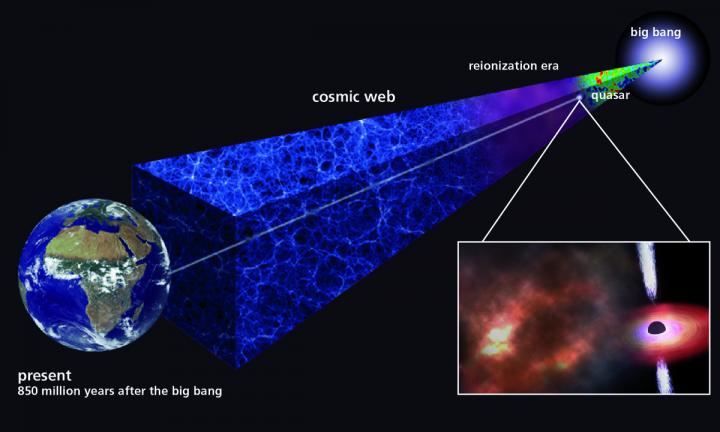

The Big Bang started the universe as a hot, murky soup of extremely energetic particles that was rapidly expanding. As this material spread out, it cooled, and the particles coalesced into neutral hydrogen gas. The universe stayed dark, without any luminous sources, until gravity condensed matter into the first stars and galaxies.

All stars, including this first generation, act as chemical factories, synthesizing almost all of the elements that make up the world around us. When the original stars exploded as supernovae, they spewed out the elements that they created, seeding the surrounding gas. Subsequent generations of stars incorporated these elements and steadily increased the chemical abundances of their surroundings.

But the first stars formed in a still pristine, cold universe. Consequently these initial stars produced elements in different proportions than those synthesized by younger stars, which were formed in an environment that was already enriched by earlier generations.

“Looking back in time far enough, one may expect cosmic gas clouds to show the tell-tale signature of the peculiar element ratios made by the first stars,” said Rauch. “Peering even further back, we may ultimately witness the disappearance of most elements and the emergence of pristine gas.”

Astronomers have long used quasars to learn about the chemical composition of cosmic gas over time, showing how different generations of stars enrich their surroundings.

“We found this ancient gas cloud when following up on an inventory of very distant quasars using the Magellan telescopes at Carnegie’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile,” explained Bañados, who is now a group leader at the Max-Planck Institute in Heidelberg.

Quasars are tremendously luminous objects comprised of enormous black holes accreting matter at the centers of massive galaxies. Because the gas cloud exists between the quasar and us on Earth, the quasar’s incredibly bright light must pass through it to get to us and astronomers can take advantage of this to understand the cloud’s chemistry. This discovery presented an unprecedented opportunity to characterize a gas cloud from the first billion years of cosmic history.

The team found that the cloud’s chemical makeup was quite modern, and not as primitive as expected if dominated by the first stars. Although it formed only 850 million years after the Big Bang, its chemical abundances were already as high as those typically seen in cosmic gas clouds that were formed several billion years later.

“Apparently, the first generation of stars had already expired by the time the cloud formed,” Rauch explained. “This shows that the universe was rapidly swamped by the chemical products of later generations of stars, even before most of the present-day galaxies were in place.”

The team is optimistic that even-more-ancient gas clouds will eventually be discovered and that they will reveal information about the first stars in the universe.

###

This work was supported by an ERC grant Cosmic Dawn; a U.S. National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship; and direct funding from the MIT Undergraduate Research Opportunity program.

The Carnegie Institution for Science (carnegiescience.edu) is a private, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with six research departments throughout the U.S. Since its founding in 1902, the Carnegie Institution has been a pioneering force in basic scientific research. Carnegie scientists are leaders in plant biology, developmental biology, astronomy, materials science, global ecology, and Earth and planetary science.

Media Contact

Michael Rauch

[email protected]