The finding suggests a potential target in the metabolism that could slow or prevent breast cancer metastasis

Credit: University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center

ANN ARBOR, Michigan — Cancer cells – especially the more aggressive ones – seem to have an ability to change. It’s how they evade treatment and spread throughout the body.

But how does a cancer cell get the energy it needs to do this?

“We wondered if a cancer cell that wants to change its function can redirect energy not because it takes on new energy but because it has a stored reservoir of potential energy,” says Sofia D. Merajver, M.D., Ph.D., professor of internal medicine and epidemiology at the University of Michigan and a researcher at the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center.

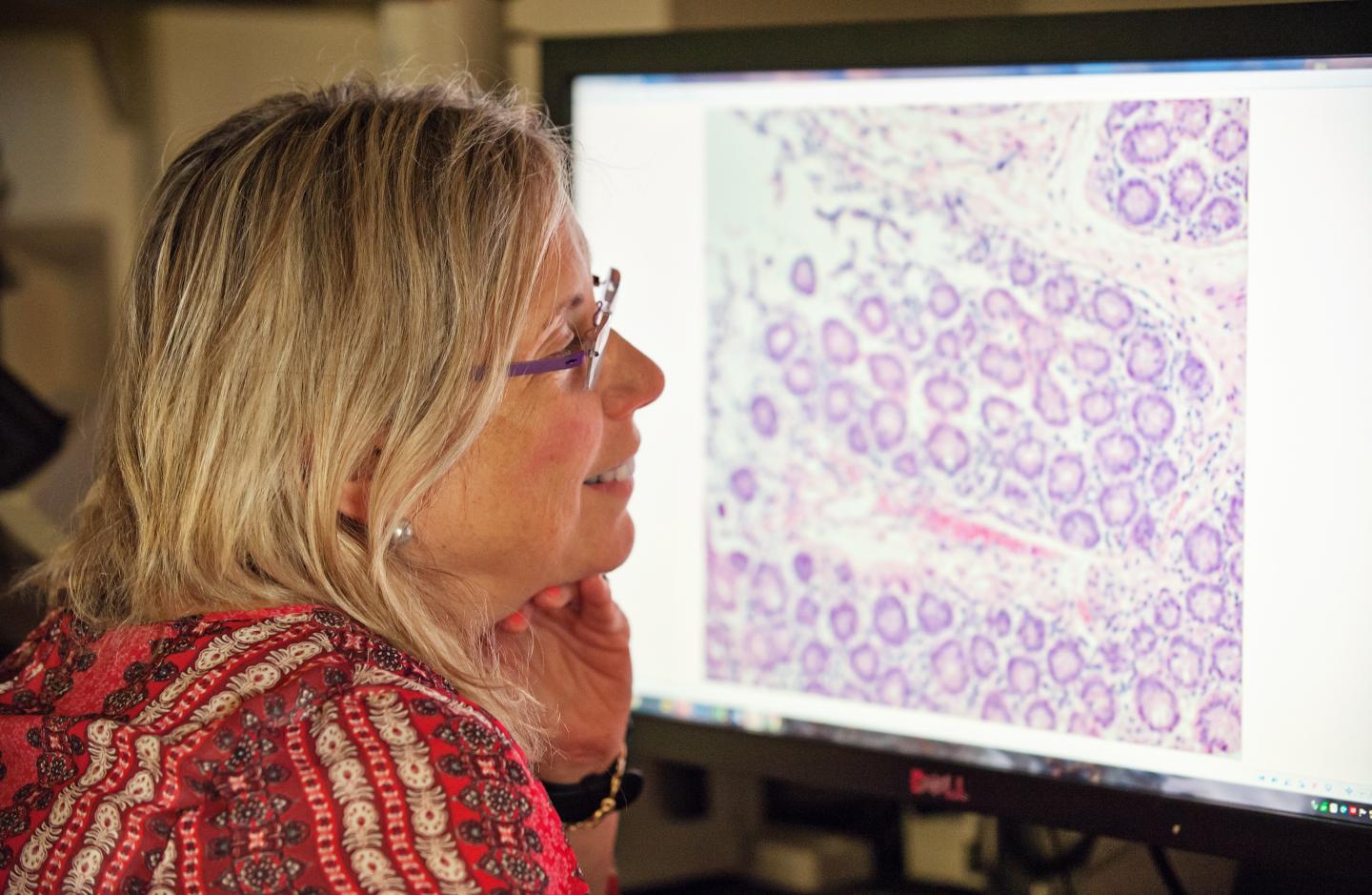

Merajver’s lab looked at levels of glycogen, which represents a stored collection of glucose molecules. Glucose converts to energy, which cancer uses to grow, spread and metastasize.

The team measured glycogen levels in cell lines representing triple-negative breast cancer, inflammatory breast cancer, hormone receptor positive breast cancer and normal breast cells.

The study, published in PLOS ONE, found that aggressive cancers stored glycogen in very large amounts, depending on available oxygen. It’s on the order of what’s stored in the liver – an organ whose key function is storing glycogen.

“It was surprising just how much glycogen these cancer cells were storing,” Merajver says. “This means the cancer has that whole amount of glycogen ready to break down into glucose molecules when the need arises.”

Even more surprising, the researchers found that an enzyme controlling glycogen degradation in the brain played a key role in glycogen control in breast cancer. The enzyme PYG exists in several forms, including brain and liver. PYGB is primarily expressed in the brain.

Researchers knocked down PYGB in breast cancer cells and found the cells could not use these energy stores and became much less aggressive. They did not see the same effect in the normal breast cells.

“This is a completely new way to look at the plasticity of breast cancer cells,” Merajver says. “We think that this ability to change, for breast cancer cells to rewire themselves depending on their environment, is why many patients become resistant to precision medicines. Our study shows one way the cancer cells do this is by creating a reservoir of building blocks or energy.”

Researchers believe PYGB could be a potential target to treat or prevent breast cancer metastases. Further studies will explore this link in animal models. Researchers will also investigate whether glycogen phosphorylases inhibitors, which have been studied in diabetes and heart disease, might slow or stop cancer metastasis.

###

Additional authors: Megan A. Altemus, Laura E. Good, Andrew C. Little, Joel A. Yates, Hannah G. Cheriyan, Zhi Fen Wu

Funding: University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center Nancy Newton Loeb Fund, National Institutes of Health grants T32CA009676 and P30CA046592, Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Metavivor Foundation

Disclosure: None

Reference: PLOS ONE, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220973, published online Sept. 19, 2019

Resources:

University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center, http://www.

Michigan Health Lab, http://www.

Michigan Medicine Cancer AnswerLine, 800-865-1125

Media Contact

Nicole Fawcett

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.