Insulin signaling helps hungry mother worms make sure the next generation fares better in the face of famine

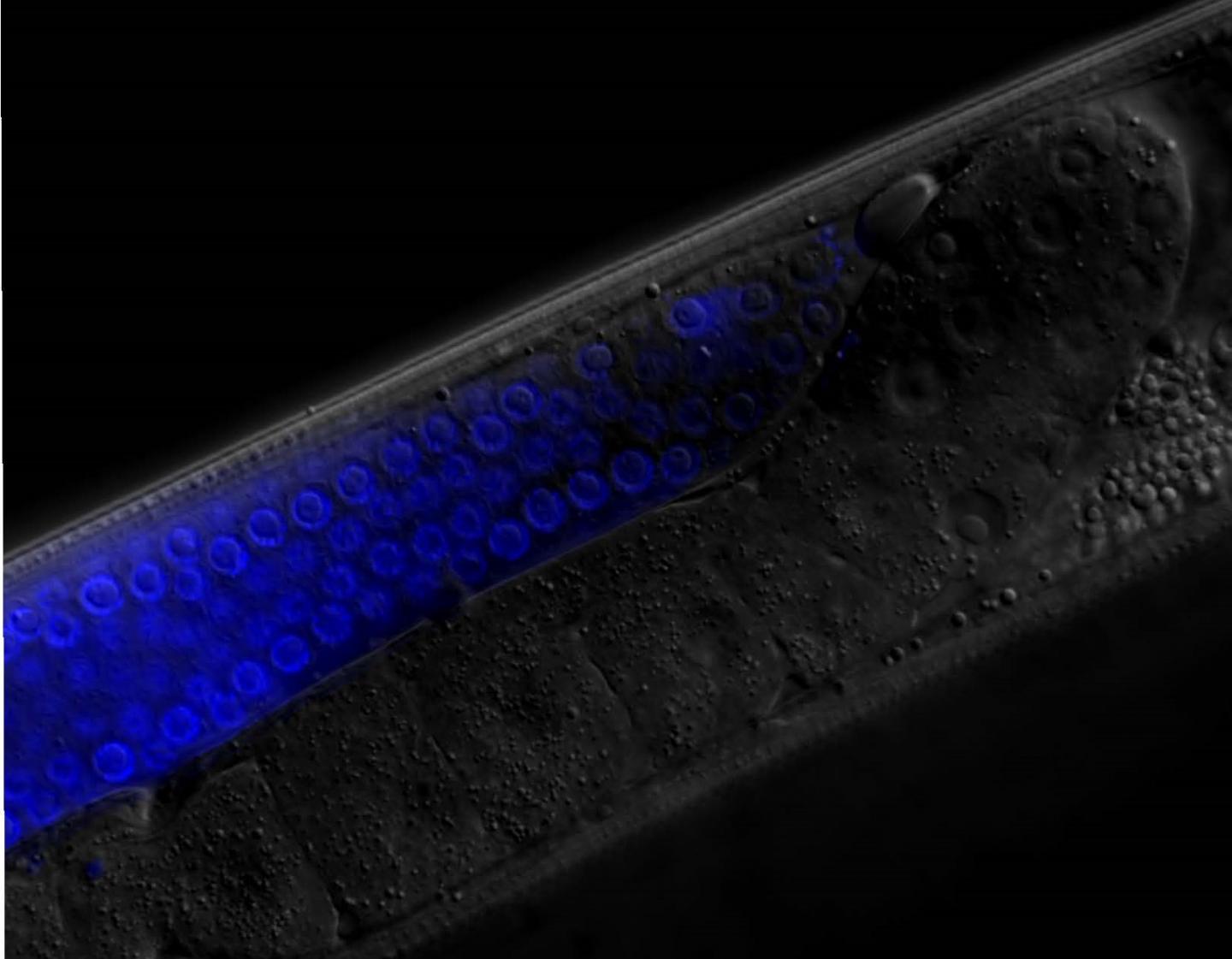

Credit: Image courtesy of Jim Jordan, Duke University

DURHAM, N.C. — Numerous studies show that the legacy of hardship can be passed from one generation to the next. The good news is that resilience can cross generations too.

That’s the takeaway from a Duke University study of C. elegans worms and their offspring. The researchers found that offspring of mothers who ate fewer calories during pregnancy were better able to bounce back from starvation themselves. The researchers also showed how a mother worm transmits her hard-won coping abilities to the next generation: via changes in insulin signaling that are transferred via her eggs to her offspring, and which help them make a better recovery from famine.

The results were published July 4 in the journal Current Biology.

C. elegans is a harmless millimeter-long worm that lives in soils and rotting vegetation, where it feeds on bacteria and other microbes. “Life in the wild is feast or famine for the worm,” said Duke associate professor of biology Ryan Baugh.

A team led by Baugh and Ph.D. student James Jordan examined what happened to two generations of worms when food is in limited supply. One group of worms received as much food as they liked. Worms in another group got a watered-down diet.

The offspring of both groups were then completely deprived of food for the first eight days of life before returning to normal eating, and assessed once they reached adulthood.

The researchers found that offspring that were starved in early life developed reproductive abnormalities later on, despite being well-fed for the rest of their growing up. But surprisingly, worms were more likely to avoid such health problems and develop normally as adults if their mothers had been underfed during pregnancy.

The researchers identified the hormones that underlie the mother’s protective effect. Reducing a mother’s food supply depresses insulin signaling, a biochemical pathway that regulates carbohydrate metabolism in both worms and vertebrates like us.

These changes affect the way she provisions her eggs. She packs them with higher concentrations of yolk protein so her larvae have something else to rely on when food is likely to be in short supply. The boost in egg yolk, in turn, alters insulin signaling in her offspring, which buffers them from early starvation’s long-reaching consequences on fertility.

The researchers acknowledge that it’s not always safe to assume the future will resemble the past. “The animals could get it wrong. The environment could change,” Baugh said. But the food levels a mother experiences during pregnancy are a reasonably reliable indicator of the future for her offspring, he explained — if the mother happens to be a worm.

“We’re only talking 12 to 16 hours from when she lays eggs to when they actually hatch,” Baugh said. The dwindling food supplies she experienced could be a harbinger of “the food supply collapsing and the population starving.”

The worms essentially retain a physiological “memory” of their mother’s experience that helps them anticipate and adapt to lean times to come, all without changing their DNA sequence, Baugh explained.

“It’s neat because it’s not the idea of heredity most of us were taught growing up,” Baugh said. “It turns out there are a variety of hereditary mechanisms besides DNA.”

###

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM117408, R01GM061706).

CITATION: “Insulin/IGF Signaling and Vitellogenin Provisioning Mediate Intergenerational Adaptation to Nutrient Stress,” James Jordan, Jonathan Hibshman, Amy Webster, Rebecca Kaplan, Abigail Leinroth, Ryan Guzman, Colin Maxwell, Rojin Chitrakar, Elizabeth Anne Bowman, Amanda Fry, E. Jane Albert Hubbard and Ryan Baugh. Current Biology, July 4, 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.062

Media Contact

Robin Ann Smith

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.