Credit: Bodleian Library, Oxford

Simon Forman and his protégé Richard Napier were infamous in early 17th-century England for their apparent ability to diagnose and even cure all kinds of ailments – from bewitchment to the “bloody flux” – by consulting the planets and stars.

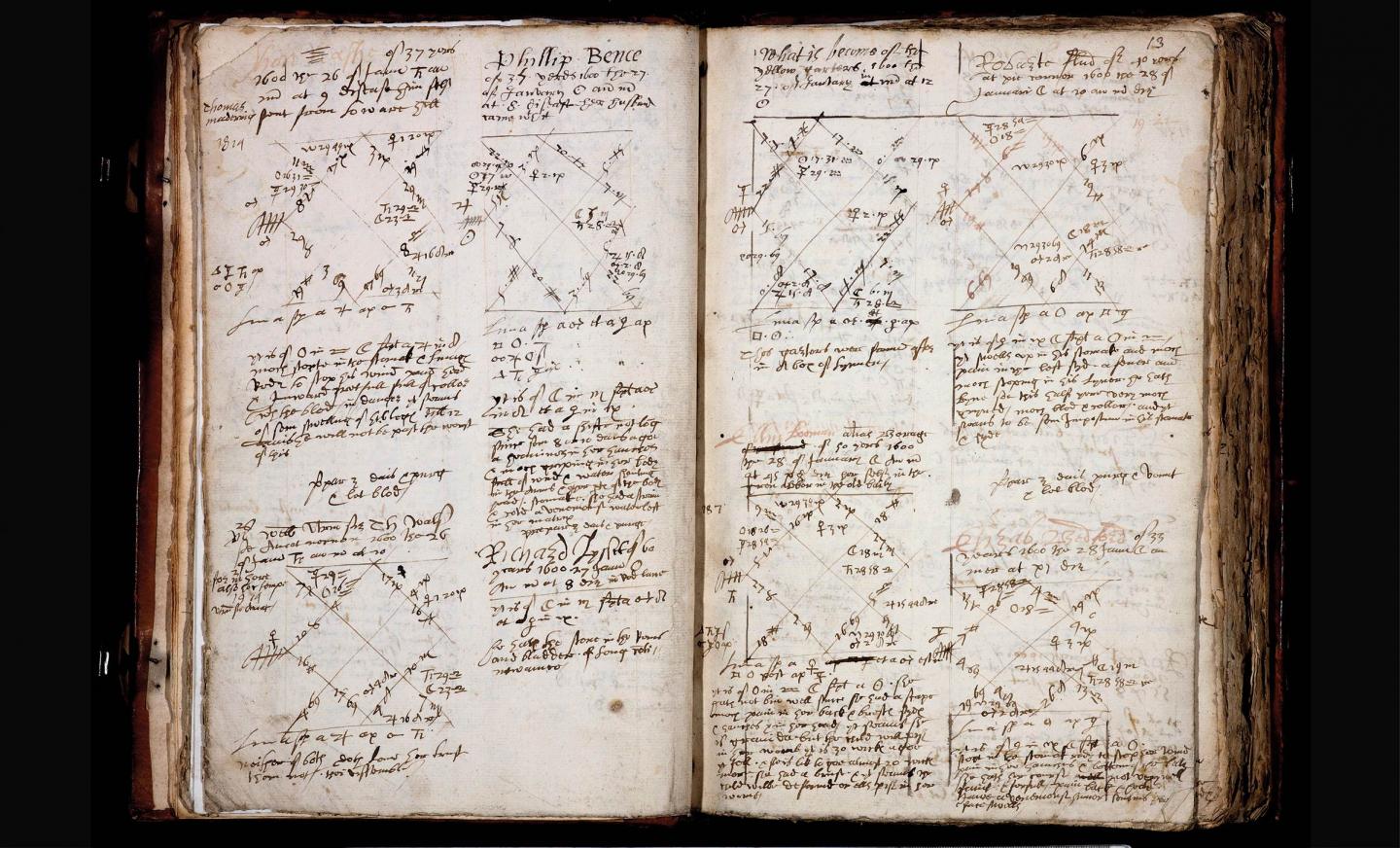

However, for historians who tried to study the notes of 80,000 cases these astrologer-physicians left behind, another notch was added to their notoriety: the perennial doctor’s trait of illegible handwriting.

Now, to mark the end of a decade spent digitising one of history’s largest surviving sets of medical records, a team of Cambridge researchers have picked their 500 favourite cases and rendered them readable – if not entirely comprehensible – for modern audiences.

Meet John Wilkingson, hair lost to the “French disease” and “thrust with a rapier in his privy parts”, or Joan Broadbrok, who “thinks her children to be rats & mice”, and Edward Cleaver, whose ill thoughts (“kisse myne arse”) may stem from the witchery of a puppy-suckling neighbour.

Ranging from lost animals to angelic visitations, bad dreams to bad marriages, and accounts of delirium, depression, and lovesickness, the transcribed cases are a trap door into the complete casebooks: an arcane archive of magic and medicine that has puzzled and fascinated scholars of history and the occult for centuries.

The transcriptions are now online here: https:/

“Our transcriptions are the very tip of the iceberg: thousands of pages of cryptic scrawl full of astral symbols, recipes for strange elixirs, and details from the lives of lords and cooksmaids suffering with everything from dog bites to broken hearts,” said Prof Lauren Kassell.

“It’s taken ten years to sift through, edit and digitise all of the cases of Forman and Napier. The Casebooks Project has opened a wormhole into the grubby and enigmatic world of seventeenth-century medicine, magic and the occult,” said Kassell, from Cambridge’s History and Philosophy of Science Department.

“Channeled through the astrologers’ pens are fragments of the health and fertility concerns, bewitchment fears and sexual desires from thousands of lives otherwise lost to history.”

Over the years the casebooks team developed an intuition for deciphering the seemingly impenetrable scripts, enabling them to transcribe and explain these strange records. Their favourite 500 cases include modern spelling and punctuation to make them easier to read.

“Napier produced the bulk of preserved cases, but his penmanship was atrocious and his records super messy,” said Kassell. “Forman’s writing is strangely archaic, like he’d read too many medieval manuscripts. These are notes only intended to be understood by their authors.”

Simon Forman was a rake and master of occult arts who turned to healing after curing himself of plague in 1592. A self-styled expert in celestial influences, he set up shop in London as a doctor who could use the stars to determine disease or predict solutions to problems as diverse as hauntings, heart pains and lost hawks.

Forman was hounded by the medical establishment of the time, who considered him a “quack”, but his popular practice was continued by Richard Napier, a country rector and his astrological protégé, when he died in 1611. Napier died in 1634.

The astrologers worked on a “horary” basis, meaning their clients posed a question – most commonly “what’s my disease?” – and the doctors would read the planetary positions at the point a question was received to divine answers.

This resulted in case notes containing specific times and dates, as well as names, locations, and hastily scribbled details of the client’s query – all recorded “in the moment”. Most have a chart of the astrological reading – the twelve celestial houses – a “judgement” of the causes of disease and remedies for relief.

“Recommended treatments are mainly purges, fortifying brews or bloodletting,” said Kassell. “A purge, upwards or downwards, was induced by a potent concoction. Ill health was considered an imbalance in the body, corrected by expulsion of blood or bile.” Pigeon slippers (“a pigon slitt & applied to the sole of each foote”) and the touch of a dead man’s hand were also prescribed to some poor souls.

Napier was a connoisseur of leeches, preferring “Dorchester…but beakinsfild better”. He also, on occasion, sought second opinions from angels, who offered blunt diagnoses such as “he will die shortly”.

Harmful or suicidal thoughts were often considered to be witchcraft or demonic visitations, and the astrologers sold “counter-spells” of incantations, sigils or blessed amulets. “The evil eye is in play throughout the casebooks,” said Kassell.

She argues that just the opportunity to discuss your problem was likely part of the astrologers’ appeal for many. “The approach taken by Forman and Napier may have worked as a form of proto-therapy. For example, many women talked openly about their sex lives and fertility fears.”

The project has inspired a new game, Astrologaster, released earlier this month, in which the player inhabits Forman as he chases women, magic and a medical license – pursuits that consumed the real man. Kassell worked closely with the game designers, who used people from real cases, including Emilia Lanier, thought by some to be Shakespeare’s ‘Dark Lady’ or even the bard himself.

“Until now, scholars that ventured into the casebooks in search of notable names and anxieties and afflictions of the age found navigation to be gruelling. Our vast digital project has changed all that, and will send future generations tumbling down the casebooks rabbit-hole,” said Kassell.

“We encourage people to use the transcriptions as a taster, before plunging into the thicket of scribbles and symbols. The cases of Forman and Napier may well suck you in.”

###

Media Contact

Lauren Kassell

[email protected]