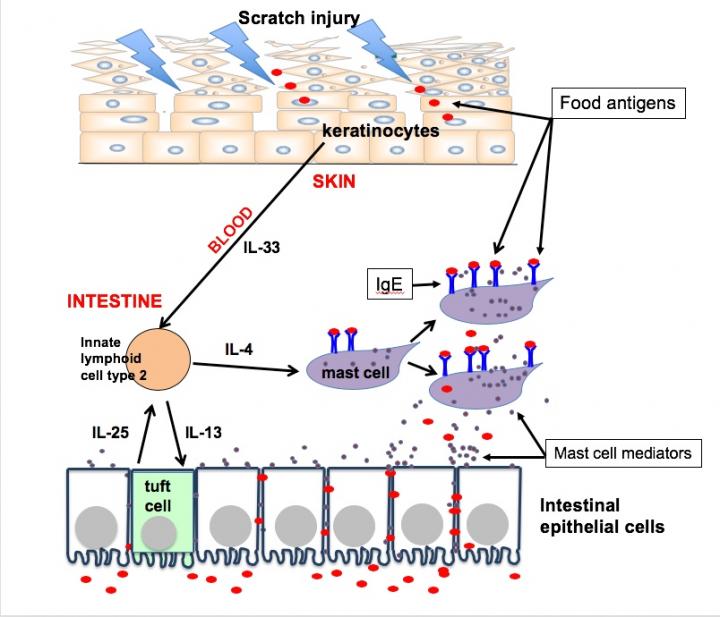

Scratching sparks a chain reaction that expands and activates intestinal mast cells

Credit: Adapted from Manuel Leyva-Castillo and Raif Geha / Boston Children’s Hospital

Eczema, a chronic itchy inflammatory skin disease, affects about 15 percent of U.S. children. It’s a strong risk factor for food allergies — more than half of children with eczema are allergic to one or more foods — and most people with food allergy have eczema. But the connection between the two hasn’t been clear. New research in a mouse model, published last week in the journal Immunity, shows for the first time that scratching the skin promotes allergic reactions to foods, including anaphylaxis.

The study, led by Raif Geha, MD, and Manuel Leyva-Castillo, PhD, at Boston Children’s Hospital, also teases out the complex web of cellular signals that elicit scratching’s dangerous effects.

When food gets under your skin

Babies, classically messy eaters, tend to rub their food on their skin. If they also have eczema, food antigens can get into the body through skin breaks caused by scratching. The immune system then produces IgE antibodies against the food.

“That’s how they get sensitized,” says Geha, chief of the Division of Immunology at Boston Children’s. How sensitive, he says, “depends on how much they scratch.”

Once formed, the IgE antibodies bind to immune cells known as mast cells. When food is ingested, mast cells fire off chemicals that act on tissue to produce an allergic response.

But there’s been a mystery: while people with food allergy have high levels of IgE antibodies in their blood, not all people with IgE antibodies are food-allergic. Also, while mast cells fire when stimulated by IgE and allergen, the strength of this firing varies between individuals.

“Our question was, what is the determinant of anaphylaxis?” says Geha.

How scratching hyper-stimulates mast cells

The study shows how mechanical skin injury provides the necessary push to fully rev mast cells up. In the mouse model, Geha, first author Manuel Leyva-Castillo, PhD, and colleagues showed that skin breaks (created by stripping off a piece of tape, rather than scratching) spark a chain reaction in the distant small intestine, expanding and activating the mast cells that spur allergic reactions (see schematic).

Tape stripping increased the permeability of the intestine, making it easier for allergens to be absorbed into the blood circulation. This caused the mice to have anaphylactic reactions when fed foods they were sensitized to, as evidenced by a drop in body temperature and markers in their blood. Mice that were similarly sensitized but did not undergo tape stripping had less severe allergic reactions.

Finally, turning to humans, Geha and colleague examined duodenal biopsies from four children with eczema and four children without eczema. They found more mast cells in the eczema group, independent of IgE levels.

Take-aways for eczema sufferers (and parents)

The bottom line is that your mother was right: If you have eczema, you shouldn’t scratch.

“The skin is the major portal for food allergy sensitization,” says Geha. “You have to seal the skin and give medications to reduce the itching.”

Like many clinicians, he also recommends keeping the skin moist after a bath and sealing it with an emollient, commercial products or even Crisco, margarine or olive oil. Dry skin is more prone to both itching and mechanical injury from scratching.

A natural protector gone wrong

It may seem strange that there would be crosstalk between the skin and the intestine. But Geha speculates that food allergy is “collateral damage” from an immune mechanism designed to protect against intestinal parasites entering the body through the skin.

“Mast cells are very important in getting rid of parasites in the gut,” he says.

###

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI113294-01A1 and U19 AI117673) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (5T32AI007512-32).

About Boston Children’s Hospital

Boston Children’s Hospital, the primary pediatric teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School, is home to the world’s largest research enterprise based at a pediatric medical center. Its discoveries have benefited both children and adults since 1869. Today, more than 3,000 scientists, including nine members of the National Academy of Sciences, 17 members of the National Academy of Medicine and 11 Howard Hughes Medical Investigators comprise Boston Children’s research community. Founded as a 20-bed hospital for children, Boston Children’s is now a 415-bed comprehensive center for pediatric and adolescent health care. For more, visit our Vector and Thriving blogs and follow us on social media @BostonChildrens, @BCH_Innovation, Facebook and YouTube.

Media Contact

Bethany Tripp

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.