The tangled highway of blood vessels that twists and turns inside our bodies, delivering essential nutrients and disposing of hazardous waste to keep our organs working properly has been a conundrum for scientists trying to make artificial vessels from scratch. Now a team from Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) has made headway in fabricating blood vessels using a three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting technique.

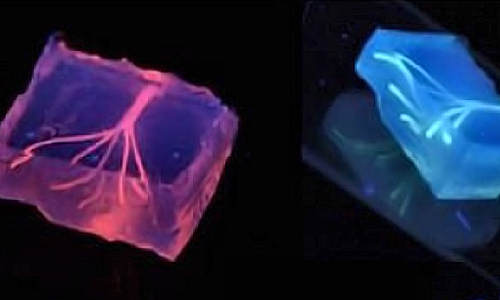

Artificial blood vessels are created using hydrogel constructs that combine advances in 3-D bioprinting technology and biomaterials. Photo Credit: Image courtesy of Khademhosseini Lab

The study is published online this month in Lab on a Chip.

“Engineers have made incredible strides in making complex artificial tissues such as those of the heart, liver and lungs,” said senior study author, Ali Khademhosseini, PhD, biomedical engineer, and director of the BWH Biomaterials Innovation Research Center. “However, creating artificial blood vessels remains a critical challenge in tissue engineering. We’ve attempted to address this challenge by offering a unique strategy for vascularization of hydrogel constructs that combine advances in 3D bioprinting technology and biomaterials.”

The researchers first used a 3D bioprinter to make an agarose (naturally derived sugar-based molecule) fiber template to serve as the mold for the blood vessels. They then covered the mold with a gelatin-like substance called hydrogel, forming a cast over the mold which was then reinforced via photocrosslinks.

“Our approach involves the printing of agarose fibers that become the blood vessel channels. But what is unique about our approach is that the fiber templates we printed are strong enough that we can physically remove them to make the channels,” said Khademhosseini. “This prevents having to dissolve these template layers, which may not be so good for the cells that are entrapped in the surrounding gel.”

Khademhosseini and his team were able to construct microchannel networks exhibiting various architectural features. They were also able to successfully embed these functional and perfusable microchannels inside a wide range of commonly used hydrogels, such as methacrylated gelatin or poly(ethylene glycol)-based hydrogels at different concentrations.

Methacrylated gelatin laden with cells, in particular, was used to show how their fabricated vascular networks functioned to improve mass transport, cellular viability and cellular differentiation. Moreover, successful formation of endothelial monolayers within the fabricated channels was achieved.

“In the future, 3D printing technology may be used to develop transplantable tissues customized to each patient’s needs or be used outside the body to develop drugs that are safe and effective,” said Khademhosseini.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Brigham and Women’s Hospital.