VANCOUVER—In spring 2018, Dr. Philip Matthews spent a typical afternoon capturing dragonflies in the University of British Columbia’s (UBC) experimental ponds. Little did the zoologist know he was about to embark on a journey to solve a century-old entomological mystery involving a much smaller, but equally intriguing, insect. As he worked in the ponds, larvae floating in rainwater in a nearby cattle tank caught his eye.

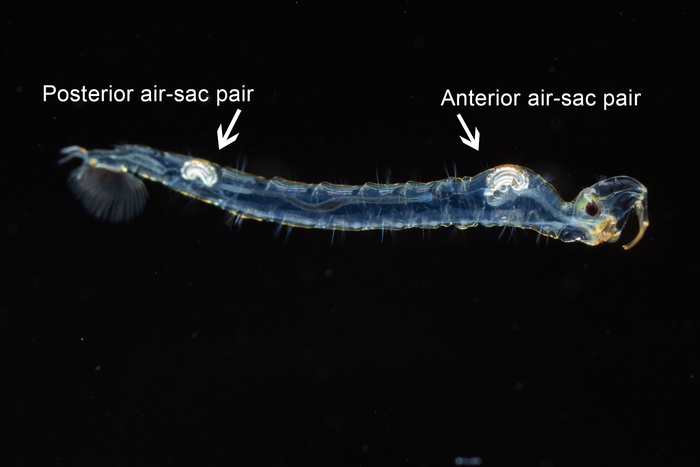

The insects were the freshwater aquatic larvae of the Chaoborus midge, also called the ‘phantom midge’ due to its near transparency. The transparency makes the larvae resemble tiny ghosts as they move through lakes, ponds and puddles.

“These bizarre insects were floating neutrally buoyant in the water, which is something you just don’t see insects doing,” said Dr. Matthews. “Some insects can become neutrally buoyant for a short time during a dive, but Chaoborus larvae are the only insects close to being neutrally buoyant.”

Solving a 100-year-old mystery with a Nobel connection

Some fish regulate their buoyancy by inflating a swim bladder with oxygen unloaded from the hemoglobin in their blood. In 1911, Nobel laureate August Krogh discovered Chaoborus larvae use a completely different mechanism, regulating their buoyancy using two pairs of internal air-filled sacs. But he never figured out how the insects adjusted the volume of their sacs without having blood or hemoglobin like vertebrates do.

A serendipitous discovery

Back in the lab after his coffee, Dr. Matthews mounted the air-sacs of the larvae from the cattle tank on a microscope that just happened to have ultraviolet light illuminating the microscope’s stage. The air-sacs started glowing blue.

The blue fluorescence was due to resilin—an almost a perfect rubber found in parts of insects where elasticity is key, as in the elastic energy that powers a flea’s incredible jump.

“The weird thing about resilin is that not only is it really elastic. It will swell if you make it alkaline and contract if you make it acidic.”

With PhD student Evan McKenzie driving experimental investigations, the researchers discovered that the insect doesn’t secrete gas into their air-sacs to make them expand. Instead, they change the pH level of the air-sac wall, the bands of resilin within the air-sac wall swell or contract in response, and the volume of the sac adjusts.

The Chaoborus air-sacs function as mechanochemical engines, converting changes in chemical potential energy into mechanical work.

“This is a really bizarre adaptation that we didn’t go looking for,” says Dr. Matthews. “We were just trying to figure out how they can float in water without sinking!”

The findings were published this week in Current Biology.

Credit: Philip Matthews

VANCOUVER—In spring 2018, Dr. Philip Matthews spent a typical afternoon capturing dragonflies in the University of British Columbia’s (UBC) experimental ponds. Little did the zoologist know he was about to embark on a journey to solve a century-old entomological mystery involving a much smaller, but equally intriguing, insect. As he worked in the ponds, larvae floating in rainwater in a nearby cattle tank caught his eye.

The insects were the freshwater aquatic larvae of the Chaoborus midge, also called the ‘phantom midge’ due to its near transparency. The transparency makes the larvae resemble tiny ghosts as they move through lakes, ponds and puddles.

“These bizarre insects were floating neutrally buoyant in the water, which is something you just don’t see insects doing,” said Dr. Matthews. “Some insects can become neutrally buoyant for a short time during a dive, but Chaoborus larvae are the only insects close to being neutrally buoyant.”

Solving a 100-year-old mystery with a Nobel connection

Some fish regulate their buoyancy by inflating a swim bladder with oxygen unloaded from the hemoglobin in their blood. In 1911, Nobel laureate August Krogh discovered Chaoborus larvae use a completely different mechanism, regulating their buoyancy using two pairs of internal air-filled sacs. But he never figured out how the insects adjusted the volume of their sacs without having blood or hemoglobin like vertebrates do.

A serendipitous discovery

Back in the lab after his coffee, Dr. Matthews mounted the air-sacs of the larvae from the cattle tank on a microscope that just happened to have ultraviolet light illuminating the microscope’s stage. The air-sacs started glowing blue.

The blue fluorescence was due to resilin—an almost a perfect rubber found in parts of insects where elasticity is key, as in the elastic energy that powers a flea’s incredible jump.

“The weird thing about resilin is that not only is it really elastic. It will swell if you make it alkaline and contract if you make it acidic.”

With PhD student Evan McKenzie driving experimental investigations, the researchers discovered that the insect doesn’t secrete gas into their air-sacs to make them expand. Instead, they change the pH level of the air-sac wall, the bands of resilin within the air-sac wall swell or contract in response, and the volume of the sac adjusts.

The Chaoborus air-sacs function as mechanochemical engines, converting changes in chemical potential energy into mechanical work.

“This is a really bizarre adaptation that we didn’t go looking for,” says Dr. Matthews. “We were just trying to figure out how they can float in water without sinking!”

The findings were published this week in Current Biology.

Journal

Current Biology

DOI

10.1016/j.cub.2022.01.018

Method of Research

Observational study

Subject of Research

Animals

Article Title

A pH-powered mechanochemical engine regulates the buoyancy of Chaoborus midge larvae

Article Publication Date

25-Jan-2022