New synthetic metabolic pathways for fixation of carbon dioxide could not only help to reduce the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere, but also replace conventional chemical manufacturing processes for pharmaceuticals and active ingredients with carbon-neutral, biological processes. A new study demonstrates a process that can turn carbon dioxide into a valuable material for the biochemical industry via formic acid.

Credit: Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology/Geisel

New synthetic metabolic pathways for fixation of carbon dioxide could not only help to reduce the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere, but also replace conventional chemical manufacturing processes for pharmaceuticals and active ingredients with carbon-neutral, biological processes. A new study demonstrates a process that can turn carbon dioxide into a valuable material for the biochemical industry via formic acid.

In view of rising greenhouse gas emissions, carbon capture, the sequestration of carbon dioxide from large emission sources, is an urgent issue. In nature, carbon dioxide assimilation has been taking place for millions of years, but its capacity is far from sufficient to compensate man-made emissions.

Researchers led by Tobias Erb at the Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology are using nature’s toolbox to develop new ways of carbon dioxide fixation. They have now succeeded in developing an artificial metabolic pathway that produces the highly reactive formaldehyde from formic acid, a possible intermediate product of artificial photosynthesis. Formaldehyde could be fed directly into several metabolic pathways to form other valuable substances without any toxic effects. As in the natural process, two primary components are required: Energy and carbon. The former can be provided not only by direct sunlight but also by electricity – for example from solar modules.

Formic acid is a C1 building block

Within the added-value chain, the carbon source is variable. carbon dioxide is not the only option here, all monocarbons (C1 building blocks) come into question: carbon monoxide, formic acid, formaldehyde, methanol and methane. However, almost all of these substances are highly toxic – either to living organisms (carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, methanol) or to the planet (methane as a greenhouse gas). Only formic acid, when neutralised to its base formate, is tolerated by many microorganisms in high concentrations.

“Formic acid is a very promising carbon source,” emphasizes Maren Nattermann, first author of the study. “But converting it to formaldehyde in the test tube is quite energy-intensive.” This is because the salt of formic acid, formate, cannot be converted easily into formaldehyde. “There’s a serious chemical barrier between the two molecules that we have to bridge with biochemical energy – ATP – before we can perform the actual reaction.”

The researcher’s goal was to find a more economical way. After all, the less energy it takes to feed carbon into metabolism, the more energy remains to drive growth or production. But such a path does not exist in nature. “It takes some creativity to discover so-called promiscuous enzymes with multiple functions,” says Tobias Erb. “However, the discovery of candidate enzymes is only the beginning. We’re talking about reactions that you can count along with since they’re so slow – in some cases, less than one reaction per second per enzyme. Natural reactions can happen a thousand times faster.” This is where synthetic biochemistry comes in, says Maren Nattermann: “If you know an enzyme’s structure and mechanism, you know where to intervene. Here, we benefit significantly from the preliminary work of our colleagues in basic research.”

High-throughput technology speeds up enzyme optimization

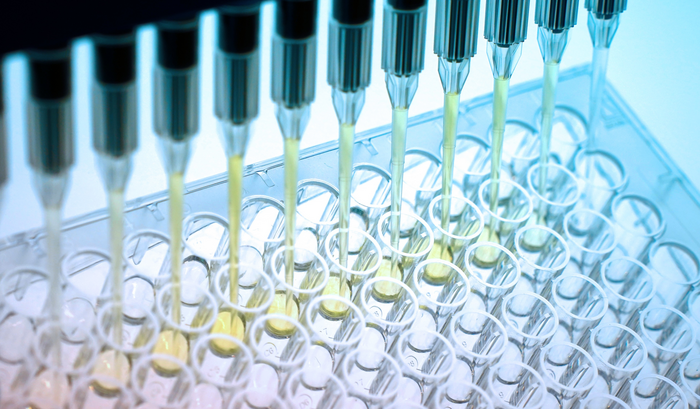

The optimization of the enzymes comprised of several approaches: building blocks were specifically exchanged, and random mutations were generated and selected for capability. “Formate and formaldehyde are both wonderfully suited because they penetrate cell walls. We can put formate into the culture medium of cells that produce our enzymes, and after a few hours convert the formaldehyde produced into a non-toxic yellow dye,” explains Maren Nattermann.

The result would not have been possible in such a short time without the use of high-throughput methods. To achieve this, the researchers cooperated with their industrial partner Festo, based in Esslingen, Germany. “After about 4000 variants, we achieved a fourfold improvement in production,” says Maren Nattermann. “We have thus created the basis for the model mikrobe Escherichia coli, the microbial workhorse of biotechnology, to grow on formic acid. For now, however, our cells can only produce formaldehyde, not convert it further.”

With collaboration partner Sebastian Wenk at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology, the researchers are currently developing a strain that can take up the intermediates and introduce them into the central metabolism. In parallel, the team is conducting research with a working group at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion headed by Walter Leitner on the electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide to formic acid. The long-term goal is an “all-in-one platform” – from carbon dioxide via an electrobiochemical process to products like insulin or biodiesel.

Journal

Nature Communications

DOI

10.1038/s41467-023-38072-w

Method of Research

Experimental study

Article Title

Engineering a new-to-nature cascade for phosphate-dependent formate to formaldehyde conversion in vitro and in vivo.

Article Publication Date

9-May-2023