Like a silent bionic army, the era of the cyborg has crept upon us.

Like a silent bionic army, the era of the cyborg has crept upon us. Or so a group of reviewers said recently when they evaluated where the science of cyborgs has led.Is this era one of super-powered, tech-enhanced humans? If you look at it through one lens, yes—today we have medical enhancements that would, a few years ago, have sent sci-fi enthusiasts into a geeked out tailspin.

But another look reveals the subtler reality: a more incremental cyborg science, played out in the bodies of bugs.

So, remote control insects are a thing…

The past few years have been saturated with stories about cyborg insects. We’ve heard about cockroaches turned into fuel cells, moths whose flight patterns we can control with implanted wires, and flying insects employable as airborne spies. Cool? Yes. Creepy? Yes. But do these bionic bugs offer a glimpse of a future that might be in store for humans as well?

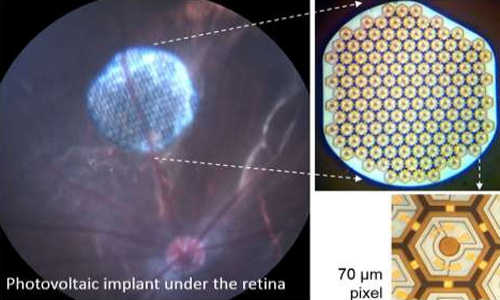

Consider that wiring up the brain of an insect can build understanding of how electronic chips embedded in human brains can help remedy Parkinson’s disease. Of course, there are ethical concerns to add to the mix: is it fair to strip independence from any living thing, even a bug, by turning it into a machine? Or on the other hand, does this robo-bug revolution in fact signal something positive about the way humans might value the long-despised critters?

“Recent developments combining machines and organisms have great potential, but also give rise to major ethical concerns,” reads the press release from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, which published the review about cyborgs.

These concerns are naturally larger when it comes to human bodies, because in the future, an enhanced ability to channel signals into a human brain might have complex, if not questionable outcomes. Insects on the other hand—physically simple, easily attainable, and ‘just bugs’ after all—provide perfect vessels for our experiments.

Alper Bozkurt, an electrical and computer engineering researcher at North Carolina State University, is part of a team that wires cockroaches up to tiny wearable radio backpacks, allowing the researchers to transmit small pulses of electricity by remote-control via the backpack and into the cockroach’s antennae. This triggers the nerves there, prompting the insect to change direction. “The cockroaches use their antennae like a blind person,” says Bozkurt, “So we think this pulse creates the sense of a barrier.”

“IT’S NOT LIKE YOU KNOW THE PATH BETWEEN YOU AND THE VICTIM,” BOZKURT SAYS—UNLESS YOU HAVE A SCURRYING ARMY OF CYBORG INSECTS TO MAP IT FOR YOU, OF COURSE

Once they discovered that the backpack-toting bugs could be steered closely along a curving line, Bozkurt and his team dreamt up other uses for the scuttling insects. That’s how they came up with the concept of ‘bugs to the rescue’.

Earthquakes and other disasters leave buildings collapsed, with victims entrapped. The challenge for rescuers lies in plotting what’s ahead. “It’s not like you know the path between you and the victim,” Bozkurt says—unless you have a scurrying army of cyborg insects to map it for you, of course.

By setting a batch of radio-equipped cockroaches free in a collapsed building, controlling their movements via electric radio signals, and tracking them as they go, the researchers hope in the future to use cockroaches to create real-time virtual maps of unknown environments.

This kind of research epitomizes the ethical concerns that some critics have: that it is unfair to exploit a living creature for human ends.

Recently, a company called Backyard Brains was at the center of an ethical storm when they began selling kits that teach school children basic neuroscience concepts by allowing them to send electric pulses into the bodies of live cockroaches. The insects are anesthetized in ice water first, and allowed to ‘retire’ comfortably once they have been used, the company points out on their website. But still, complaints and sharp criticisms have rolled in.

“RESEARCH OUT THERE CLAIMS THERE IS NO CONCEPT OF PAIN IN INSECTS”

Many deem controlling a living thing via wires and bits of machinery unethical, and causing it pain is pronounced unfair too—often regardless of how enthusiastically many of us will squash an invasive bug in our own space.

Bozkurt emphasizes that any scientist using an animal model is cautious about these issues. “We want to make sure that we are not hurting these cockroaches, and ‘hurting’ means pain,” says Bozkurt. Scientists want to avoid stressing out their many-legged subjects. But furthermore, “Research out there claims there is no concept of pain in insects.”

There’s another facet to this too. Insect cyborgs are not only valuable for their human benefits, but when incorporated into research, Bozkurt believes that “we are serving the insects. We promote the idea that they are useful for us; that we need to appreciate them.” In other words, becoming a rescue agent is probably the closest a cockroach can come to getting some positive PR.

Either way, questioning the ethics of making bionic bugs might just be a desperate act of self-preservation. After all, these critters hint at what’s in store for us.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Gizmodo and The Connectivist, Emma Bryce.

Image via The Connectivist