Methylmercury is one of the chemicals that poses the greatest threat to global public health. People ingest methylmercury by eating fish, but how does the mercury end up in the fish? A new study shows that the concentrations of so-called thiols in the water control how available the methylmercury is to living organisms.

Credit: Photo: Marlene Johansson

Methylmercury is one of the chemicals that poses the greatest threat to global public health. People ingest methylmercury by eating fish, but how does the mercury end up in the fish? A new study shows that the concentrations of so-called thiols in the water control how available the methylmercury is to living organisms.

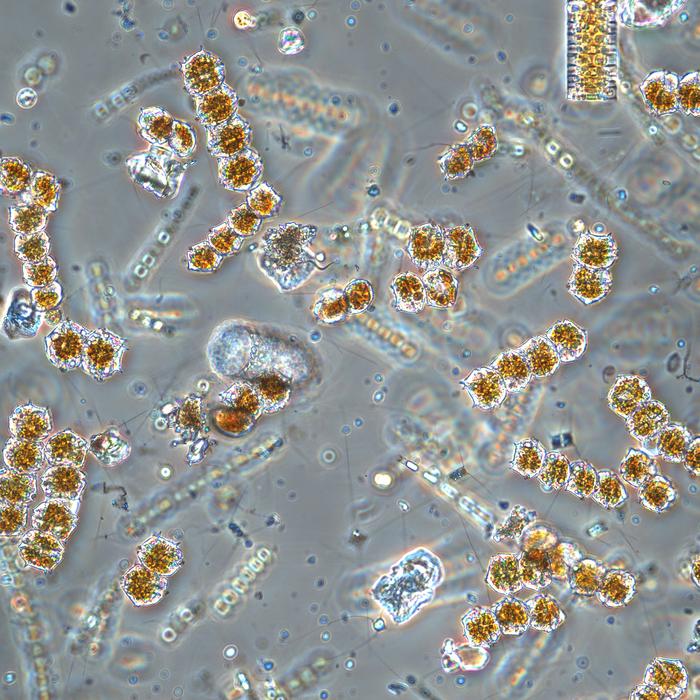

For methylmercury to enter the food web, it must be absorbed from the water by organisms and the uptake takes place primarily by phytoplankton. This results in a dramatic enrichment, where the levels of methylmercury can increase by a factor of 10,000 to 100,000. However, there is a great deal of variation between different aquatic environments, and it has so far been unclear what controls the process and why the variation is so large.

Previous studies have shown that the availability of methylmercury to living organisms increases when mercury-containing water from wetlands, streams and rivers ends up in the sea. New research shows that organic compounds called thiols in the water play a key role in this process through their ability to bind the mercury.

Lower concentrations in the sea

A research group led by Professor Erik Björn at the Department of Chemistry, Umeå University, has conducted a deep dive into these processes. The results, recently published in the scientific journal Nature Communications, show that uptake in phytoplankton is controlled by the concentrations of thiols. They bind the methylmercury strongly, and high concentrations of thiols therefore inhibit the uptake of methylmercury. Thiols are found in all organic matter dissolved in water, but the study shows that the concentrations of thiols are significantly lower in marine environments. The methylmercury that ends up in the sea will therefore not be bound as strongly, but can be absorbed by, for example, phytoplankton.

Researcher Emily Seelen conducted most of the experiments during her time as a visiting researcher at Umeå University.

“We show that the availability of methylmercury for uptake is determined by the content of thiols in the dissolved organic matter. The fact that the uptake of methylmercury is so markedly higher in marine environments compared to terrestrial environments is a direct effect of the fact that the concentrations of thiols are so much lower in the sea,” says Emily Seelen.

Complex future

Future risks of methylmercury depend mainly on how we succeed in reducing mercury emissions to the environment. However, the climate and other changes in the environment can also affect the amount and metabolism of mercury.

“In such a complex context, it is crucial to understand the key processes at the molecular level in order to be able to predict developments, assess risks and design effective measures at the ecosystem level,” says Erik Björn.

Journal

Nature Communications

DOI

10.1021/acs.est.3c03459

Method of Research

Commentary/editorial

Article Title

Mercury sources and fate in a large brackish ecosystem (the Baltic Sea) depicted by stable isotopes

Article Publication Date

13-Oct-2023