In the modern agricultural landscape of the United States, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) have become an emblematic representation of industrialized livestock production. These sprawling facilities, densely packed with hundreds or even thousands of animals, serve as a pivotal source of meat, dairy, and eggs for millions. However, their rapidly increasing prevalence has raised alarms among environmental scientists, public health experts, and social advocates alike. Recent research spearheaded by Son, Lewis, and Bell offers a comprehensive examination of the disparities in exposure to CAFOs and other animal feeding operations (AFOs) across several states, shedding new light on the environmental and health costs borne disproportionately by marginalized communities.

Animal feeding operations, especially concentrated ones, are designed for efficiency and mass production. Yet, while they fulfill a growing demand for animal products, their environmental footprint is anything but negligible. These facilities emit vast quantities of waste rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, which can infiltrate surrounding air, soil, and waterways, disrupting ecosystems and harming human health. The industrial scale and dense confinement of animals also facilitate the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and airborne pathogens, posing persistent risks to nearby populations.

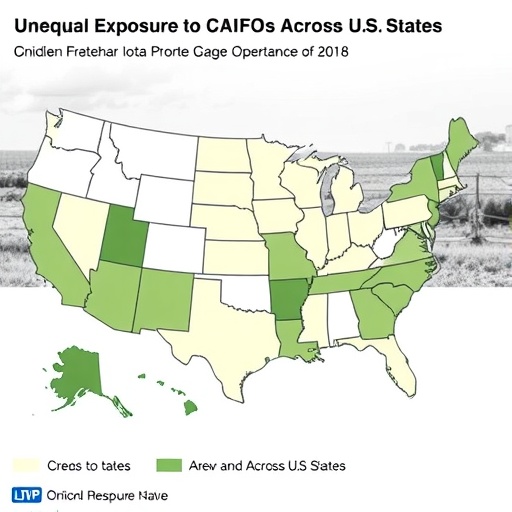

Despite mounting evidence of these hazards, the geographical placement of CAFOs has been less studied in terms of environmental justice. Son and colleagues’ work distinguishes itself by integrating demographic data with geospatial analysis of animal feeding operation distribution. Their findings challenge prior assumptions and paint a nuanced picture: certain disadvantaged communities indeed face heightened exposure, yet the trends show complexity rather than a uniform pattern. This calls for deeper scrutiny of socio-economic and racial factors influencing environmental burdens.

.adsslot_PZSelFLaCg{ width:728px !important; height:90px !important; }

@media (max-width:1199px) { .adsslot_PZSelFLaCg{ width:468px !important; height:60px !important; } }

@media (max-width:767px) { .adsslot_PZSelFLaCg{ width:320px !important; height:50px !important; } }

ADVERTISEMENT

The ecological consequences of CAFOs can be traced in multiple forms. Nitrogen-rich manure, when improperly managed, leeches into groundwater, fueling eutrophication in aquatic habitats that culminates in oxygen-depleted dead zones. These hypoxic zones devastate fish populations and biodiversity, impairing commercial and recreational fisheries. Moreover, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and ammonia released into the air contribute to photochemical smog and particulate matter formation, magnifying respiratory ailments within affected neighborhoods.

Communities adjacent to CAFOs have long voiced concerns over foul odors, increased flies, and contamination fears, yet their grievances often clash with economic interests. The agricultural sector, bolstered by subsidies and regulatory exemptions, wields significant influence in rural and semi-rural regions. Son et al. navigated this contentious terrain by systematically evaluating the distribution of CAFOs and other AFOs through state-level data spanning multiple years and diverse demographic characteristics. Their approach illuminates disparities that are sometimes overshadowed by local political dynamics and economic dependencies.

One striking revelation from the study is that while lower-income and minority populations in certain regions do experience elevated exposure to these operations, the relationship is not universally consistent across all states examined. This heterogeneity suggests that factors beyond simple socio-economic status dictate CAFO siting patterns — such as land value, zoning laws, historical agricultural practices, and political advocacy. The authors argue that policies addressing CAFO impacts must be tailored with an understanding of these regional distinctions rather than relying solely on generalized assumptions about environmental injustice.

The research also underscores the intersection of health equity and environmental regulation. Exposure to air pollutants from CAFOs correlates with asthma exacerbations, respiratory infections, and other chronic conditions that disproportionately affect vulnerable groups including children and the elderly. Furthermore, psychological stress arising from persistent nuisances and fears of contamination compounds these physical health risks. Son et al. advocate for robust environmental epidemiological surveillance paired with community engagement to forge more equitable pathways forward.

The complexity revealed by the study calls into question simplistic policy responses such as blanket bans or unchecked expansion. Instead, a multifaceted approach emphasizing transparency, community voices, and environmental monitoring is necessary. Son et al. recommend enhanced spatial and temporal tracking of emissions, coupled with targeted public health interventions and infrastructure investments in affected communities.

Notably, the study’s multi-state scope provides an unprecedented comparative lens. It enables cross-jurisdictional learning, illustrating how certain states have innovated regulatory frameworks or community engagement models to better manage CAFO impacts. Such examples may offer blueprints for broader adoption elsewhere in the country and internationally.

Ultimately, the research by Son, Lewis, and Bell reframes the discourse around CAFOs from a singular environmental hazard to a dynamic, context-dependent phenomenon involving intersecting social determinants. Their meticulous data analysis and thoughtful interpretation resonate beyond academia, inviting urgent public dialogue and concerted action to redress longstanding inequities.

As animal agriculture continues to evolve amid rising global demands and climate pressures, the implications of this study extend well into future policy and research domains. Enhanced scientific collaboration, inclusive governance processes, and technological innovation must converge to reimagine how societies produce food without sacrificing environmental integrity or social justice.

In conclusion, while concentrated animal feeding operations remain vital to modern food systems, the disparities in exposure highlighted by this research underline an urgent need for comprehensive strategies. These must integrate environmental science, public health, urban planning, and social equity to foster resilient communities capable of thriving alongside sustainable agriculture.

Subject of Research: Disparities in exposure to concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and other animal feeding operations (AFOs) across multiple states in the USA.

Article Title: Disparities in exposure to concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and other animal feeding operations across multiple states in USA.

Article References:

Son, JY., Lewis, B.M. & Bell, M.L. Disparities in exposure to concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and other animal feeding operations across multiple states in USA.

J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00783-1

Image Credits: AI Generated

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-025-00783-1

Tags: agricultural practices and healthair and water pollution from CAFOsantibiotic-resistant bacteria from CAFOsCAFO environmental impactconcentrated animal feeding operationsdisparities in CAFO exposureecological effects of animal feeding operationsenvironmental justice and agricultureindustrial livestock production in the U.S.livestock production and community healthmarginalized communities and CAFOspublic health risks of CAFOs