Imagine a pair of twins that everyone believed to be estranged, who turn out to be closer than anyone knew. A genetic version of this heartwarming tale might be taking place in our cells. We and other mammals have two copies of each gene, one from each parent. Each copy, or “allele,” was thought to remain physically apart from the other in the cell nucleus, but a new study finds that alleles can and do pair up in mammalian cells.

Intriguingly, the pairing of at least one set of alleles has been observed to coincide with a critical time in the life of a stem cell: the moment when it commits to develop into a specific cell type. This process is called differentiation.

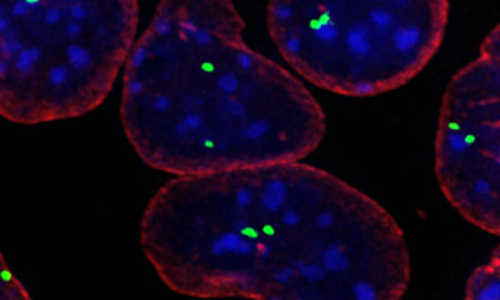

We and other mammals have two copies of each gene, and each copy, or “allele,” was thought to remain physically apart from the other in the cell nucleus. David Spector’s team now finds that the alleles of a specific gene, Oct4, can and do pair up in mammalian cells. (Oct4 gene alleles are labeled in green; other DNA is stained blue; cell nuclei are outlined in red). The Oct4 alleles were observed to pair up just as embryonic stem cells differentiated into specific cell types.

In work published today in Cell Stem Cell a team of researchers led by Professor David L. Spector at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) showed that the two alleles of Oct4, a gene important in embryonic stem cells, did not come together randomly, at any time or place, but did so at the developmental point at which stem cells begin their maturation into specific cell types.

Spector, along with Megan Hogan, Ph.D., lead author on the new paper, and colleagues, began by observing the location within the cell nucleus of various genes known to be important in stem cells. “We examined hundreds of cells, and we made the interesting and unexpected finding that the two alleles of the Oct4 gene tended to co-localize together in about 25% of the cells,” Spector says. “This was really unexpected, but it’s the sort of image that’s worth a thousand words.”

Examining enough single cells to make sure the team was observing a widespread phenomenon was no easy task. “It was a lot of work, but I think in the end the pictures that come out of it, the stories that we have gotten out if it, makes it worth it,” says Hogan, a recent doctoral student in the Spector Lab and now a postdoctoral investigator at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

To figure out if what they were seeing was physiologically important, the team studied whether they could manipulate the timing of the Oct4 pairing during differentiation. They used different methods to cause the stem cells to differentiate, and found that the more rapidly the cells differentiated, the earlier Oct4 pairing occurred. “This supported the notion that this was a potentially very exciting finding,” Spector says.

To confirm that the Oct4 pairing wasn’t something that only occurred in tissue culture, the team then looked in mouse embryos. “The pairing was equal to or even a little bit more frequent than in culture, and that was really comforting and extremely convincing to us that there is physiological relevance to this,” Spector says.

The team then wanted to figure out whether the Oct4 allelic pairing might play a role in regulating the gene’s expression, a process that eventually results in the production of the OCT4 protein. As the Oct4 alleles are not expressed after stem cell differentiation is initiated, their data suggests that Oct4 pairing occurs during the gene’s transition from an “on” to an “off” state.

One of the key questions to be answered in future research is why the Oct4 alleles come together. Spector hypothesizes that Oct4, being a key regulator of stem cell differentiation, may have to go through a special step while changing from the “on” to the “off” state.

Although the type of pairing exhibited by the Oct4 alleles has not been reported previously in mammals, it is similar to a process known as transvection that occurs frequently in fruit flies. In addition, Oct4 allele pairing exhibits similarities to the chromosomal interactions observed during X chromosome inactivation in female cells, and during V(D)J recombination in B cells of the immune system, according to Spector.

He suggests that such chromosome and allele pairing may be more common in mammals than previously thought. “One might want to look at other critical regulators of cellular or developmental processes, and there might be other cases where this also occurs,” he says. This could lead to a whole new avenue of study, and Spector and Hogan’s work could be just the beginning.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.