Bacteria on the surface of leaves survive dryness during the day by huddling in tiny droplets — a finding that may help scientists support microbiome health in crops and natural plants

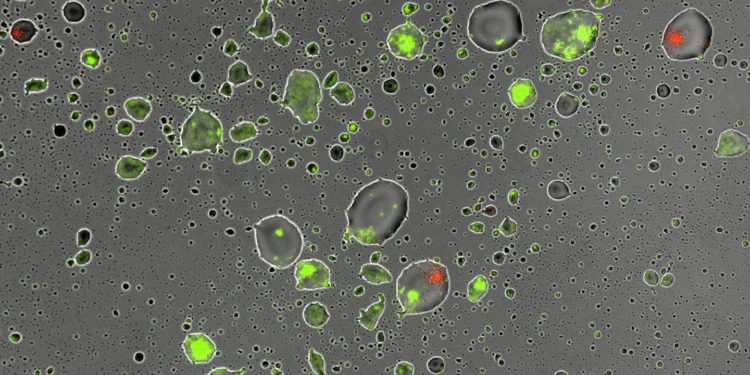

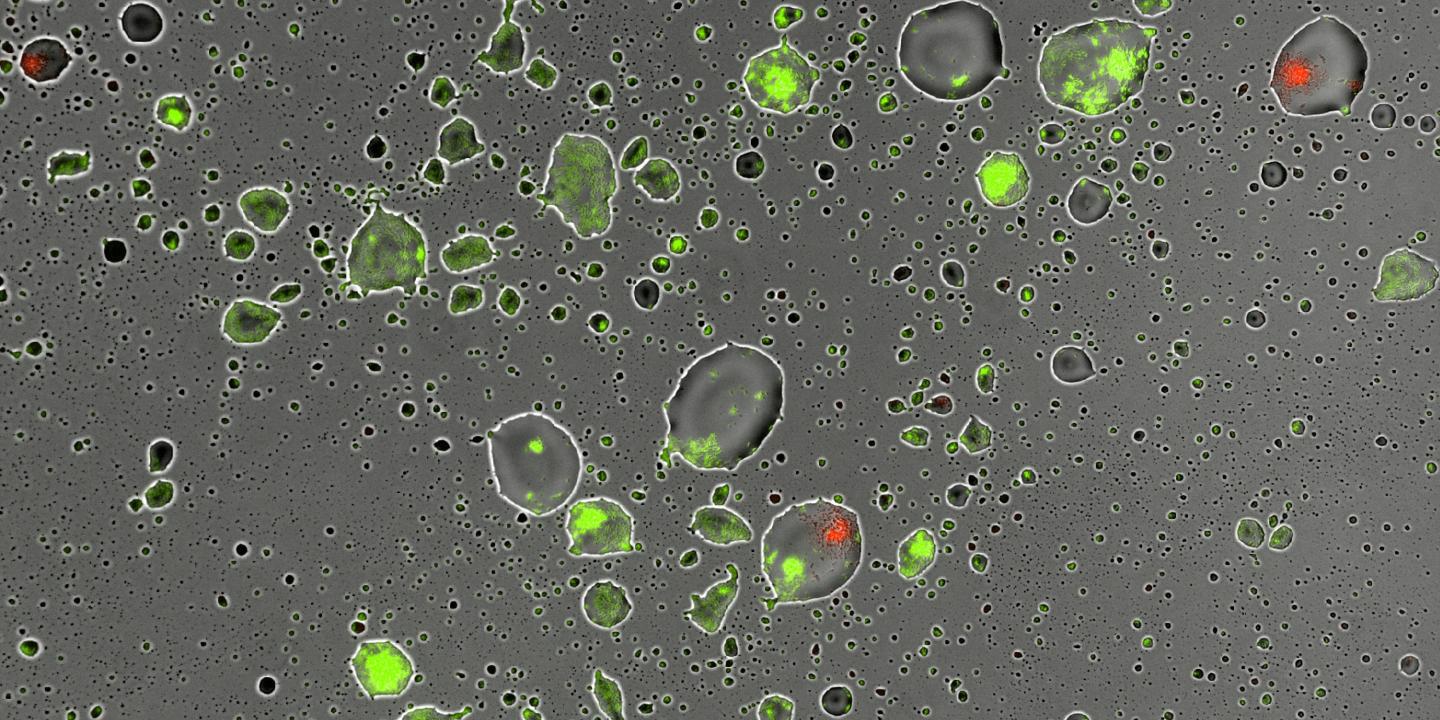

Credit: Grinberg et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Microscopic droplets on the surface of leaves give refuge to bacteria that otherwise may not survive during the dry daytime, according to a new study published today in eLife.

Understanding this bacterial survival strategy for dry conditions may enable scientists to develop practices that support healthy plant microbiomes in agricultural and natural settings.

The surface of an average plant leaf is teeming with about 10 million microbes – a population comparable to that of large cities – that contribute to the health and day-to-day functioning of the plant. Scientists have long wondered how bacteria are able to survive as daytime temperatures and sunlight dry off leaf surfaces.

“While leaves may appear to be completely dry during the day, there is evidence that they are frequently covered by thin liquid films or micrometre-sized droplets that are invisible to the naked eye,” says co-lead author Maor Grinberg, a PhD student at Hebrew University’s Robert H. Smith Faculty of Agriculture, Food, and Environment in Rehovot, Israel. “It wasn’t clear until now whether this microscopic wetness was enough to protect bacteria from drying out.”

To answer this question, Grinberg, together with co-lead author and Research Scientist Tomer Orevi and their team, recreated leaf surface-like conditions in the laboratory using glass plates that were exposed to various levels of humidity. They then conducted experiments with more than a dozen different bacteria species in these conditions.

They observed that while these surfaces appeared dry to the naked eye, under a microscope bacteria cells and aggregates were safely shielded in miniscule droplets. Interestingly, larger droplets formed around aggregates of more than one cell, while only tiny droplets formed around solitary cells. This microscopic wetness is caused by a process called deliquescence – where hygroscopic substances, such as aerosols, that are prevalent on leaves absorb moisture from the atmosphere and dissolve within the moisture to form the droplets.

“We found that bacteria cells can survive inside these droplets for more than 24 hours and that survival rates were much higher in larger droplets,” Orevi explains. “Our results suggest that through methods of self-organisation, for example by aggregation, these cells can improve their survival chances in environments frequently exposed to drying.”

These findings could have important implications for agriculture as human practices may inadvertently interfere with this bacterial survival mechanism, endangering the health of crops and natural vegetation, according to senior author Nadav Kashtan, PhD, Assistant Professor at Hebrew University’s Robert H. Smith Faculty of Agriculture, Food, and Environment. “A greater understanding of how microscopic leaf wetness may protect the healthy plant microbiome and how it might be disrupted by agricultural practices and human aerosol emissions is of great importance,” he says.

Kashtan also notes that similar microscopic surface wetness likely occurs in soil, in the built environment, on human and animal skin, and potentially even in extra-terrestrial systems where conditions might allow, suggesting such bacterial survival strategies are not limited to leaf surfaces.

###

Reference

The paper ‘Bacterial survival in microscopic surface wetness’ can be freely accessed online at https:/

Media contact

Emily Packer, Senior Press Officer

eLife

[email protected]

01223 855373

About eLife

eLife is a non-profit organisation inspired by research funders and led by scientists. Our mission is to help scientists accelerate discovery by operating a platform for research communication that encourages and recognises the most responsible behaviours in science. We publish important research in all areas of the life and biomedical sciences, including Computational and Systems Biology and Microbiology and Infectious Disease, which is selected and evaluated by working scientists and made freely available online without delay. eLife also invests in innovation through open-source tool development to accelerate research communication and discovery. Our work is guided by the communities we serve. eLife is supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Max Planck Society, the Wellcome Trust and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. Learn more at https:/

To read the latest Computational and Systems Biology research published in eLife, visit https:/

And for the latest in Microbiology and Infectious Disease, see https:/

Media Contact

Emily Packer

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.