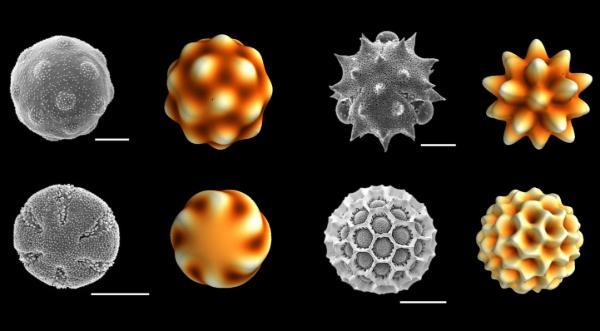

Credit: PalDat.org (SEM images) and Asja Radja (simulations)

A building’s architectural plans map out what’s needed to keep it from falling down. But design is not just functional: often, it’s also beautiful, with lines and shapes that can amaze and inspire.

Beautifully crafted architecture isn’t limited to human-made structures. Nature is rife with ornate structures, from the spiraling fractal patterns of seashells to the intricately woven array of neurons in the brain.

The microscopic world contains its fair share of intricate patterns and designs, such as the geometric patterns on individual grains of pollen. Scientists have been fascinated by these intricate structures, which are smaller than the width of a human hair, but have yet to determine how these patterns form and why they look the way they do.

Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Physics & Astronomy have developed a model that describes how these patterns form, and how pollen evolved into a diverse range of structures. Graduate student Asja Radja was the first author of the study, and worked with fellow graduate student Eric M. Horsley and former postdoc Maxim O. Lavrentovich, who is now working at the University of Tennessee. The study was led by associate professor Alison Sweeney.

Radja analyzed pollen from hundreds of flowering plant species in a microscopy database, including iris, pigweed, amaranth, and bougainvillea. She then developed an experimental method that involved removing the external layer of polysaccharide “snot” from the pollen grains, and taking high-resolution microscopic images that revealed the ornate details of the pollen as they formed at a micrometer scale.

Sweeney and Radja’s original hypothesis was that the pollen spheres are formed by a buckling mechanism. Buckling occurs when materials are strong on the outside but pliable on the inside, causing the structure to shrink inwards and form divots, or “buckles,” on the surface. But the data they collected didn’t align with their initial idea.

“Alison taught me that with any biological system, you have to really stare at it in order to figure out exactly what’s going on,” Radja says about the hours she spent studying pollen images. One of the key challenges with studying pollen was looking at the problem with a fresh perspective in order to think about what underlying physics could explain the structures.

The solution, published in Cell, represents the first theoretical physics-based framework for how pollen patterns form. The model states that pollen patterns occur by a process known as phase separation, which physicists have found can also generate geometric patterns in other systems. An everyday example of phase separation is the separation of cream from milk; when milk sits at room temperature, cream rises to the top naturally without any additional energy, like mixing or shaking.

Radja was able to show that the “default” tendency of developing pollen spores is to undergo a phase separation that then results in detailed and concave patterns. “These intricate patterns might actually just be a happy consequence of not putting any energy into the system,” says Radja.

However, if plants pause this natural pattern-formation process by secreting a stiff polymer that prevents phase separation, for example, they can control the shapes that form. These plants tend to have pollen spores that are smoother and more spherical. Surprisingly, the smooth pollen grains, which require additional energy, occur more frequently than ornate grains, suggesting that smooth grains may provide an evolutionary advantage.

This biophysical framework will now enable researchers to study a much larger class of biological materials. Sweeney and her group will see if the same rules can explain much more intricate architectures in biology, like the bristles of insects or the cell walls of plants.

Sweeney’s group is also working with materials engineer Shu Yang of Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science to develop pollen-inspired materials. “Materials that are like pollen often have super-hydrophobicity, so you can very intricately control how water will interact with the surface,” says Sweeney. “What’s cool about this mechanism is that it’s passive; if you can mimic the way pollen forms, you can make polymers go where you want them to go on their own without having to do complicated engineering that’s expensive and hard to replicate.”

###

The research was supported by the Kaufman Foundation New Initiative Award, the Packard Foundation Fellowship, the National Science Foundation CAREER Award 1351935, and a Simons Investigator Grant.

Media Contact

Erica K. Brockmeier

[email protected]

215-898-8562

Related Journal Article

http://dx.