Credit: OIST

Baking a cake from scratch is a task deemed difficult for many. Constructing an artificial cell-like system from scratch, well that’s another story.

“Synthesizing cells from scratch is of fundamental importance to understand what life is,” said Prof. Yohei Yokobayashi, leader of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) Nucleic Acid Chemistry and Engineering Unit.

Scientists around the world are beginning to create simple artificial cells that conduct some basic biological functions and that contain small strands of DNA or RNA. However, getting these snippets of genetic material to express their encoded proteins in response to precise signals has been a challenge.

Now, Yokobayashi and other researchers from OIST and Osaka University have found a way to make artificial cells interact with a wide range of chemicals. They developed a riboswitch – a gene switch that senses chemical signals – that can respond to histamine, a chemical compound that is naturally produced in the body. In the presence of this chemical, the riboswitch turns on a gene inside the artificial cells. Such a system, could one day be used as a new way of administering medicine, said Yokobayashi, a corresponding author on a recent study in Journal of the American Chemical Society, which describes the approach.

“We want the cells to release drugs based on their detection of histamine,” Yokobayashi said. “The ultimate goal is to have cells in your gut use histamine as a signal to release the appropriate amount of drug to treat a condition.”

Signal selection

The scientists chose histamine as the chemical signal for their artificial cells because it is an important biological compound in the immune system. If you feel an itch, histamine is the likely culprit. It is also released by the body during allergic reactions and helps defend against foreign pathogens by spurring inflammation.

To detect histamine, they created a molecule called an RNA aptamer. RNA aptamers are small segments of RNA building blocks that can be engineered to act as binding agents to specific target molecules. It took Yokobayashi and his colleagues, former OIST postdocs Dr. Mohammed Dwidar and Dr. Shungo Kobori and OIST PhD student Charles Whitaker, two years to create an aptamer that targeted histamine.

Next, the team developed a so-called riboswitch that would turn this signal detection into action – specifically, translating a gene to produce a protein. Normally, cells produce proteins when templates made of messenger RNA (mRNA) bind to cellular structures called ribosomes. Here, the scientists used the histamine aptamer to design a riboswitch that alters the shape of the mRNA upon binding histamine. In the absence of histamine, the shape of the mRNA prevents the ribosome from binding, and no protein is produced. Histamine-bound mRNA, however, allows ribosome to bind and synthesize proteins.

“We demonstrated that riboswitches can be used to make artificial cells respond to desired chemical compounds and signals,” Yokobayashi said.

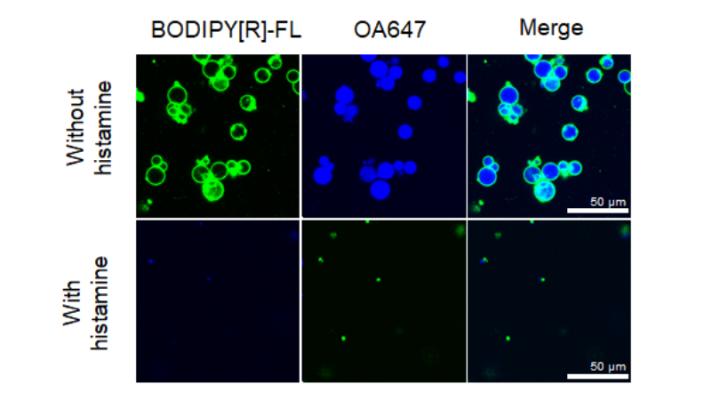

The next step resulted from a collaboration with senior author Prof. Tomoaki Matsuura and graduate student Yusuke Seike of the Department of Biotechnology at Osaka University. Matsuura and Seike put the cell-free riboswitch created by Yokobayashi’s team into lipid vesicles to create artificial cells. The Osaka team attached the riboswitch to a gene expressing a fluorescent protein, so that when the riboswitch was activated by histamine, the system glowed. Then, they controlled another protein by the riboswitch – one that makes nanometer-scale pores on the cell membrane. When the aptamer sensed histamine, a fluorescent compound encapsulated in the vesicles was released out of the cells through the pores, modeling how the system would release a drug.

The scientists also created a ‘kill switch’, which instructs the cell to self-destruct – creating a control for the technology.

The technology is in the early stages of development. The next step is to make the artificial cells more sensitive to a smaller amount of histamine. Medical use may be in the distant future, but the potential exists, the scientists say.

###

Media Contact

Tomomi Okubo

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.