SAN DIEGO, March 23, 2022 — Your next trendy handbag could be fashioned from “leather” made from a fungus. Today, researchers will describe how they have harnessed this organism to convert food waste into sustainable faux leather, as well as paper products and cotton substitutes, with properties comparable to the traditional materials. They explain that this fungal leather takes less time to produce than existing substitutes already on the market, and, unlike some, is 100% biobased.

Credit: Akram Zamani

SAN DIEGO, March 23, 2022 — Your next trendy handbag could be fashioned from “leather” made from a fungus. Today, researchers will describe how they have harnessed this organism to convert food waste into sustainable faux leather, as well as paper products and cotton substitutes, with properties comparable to the traditional materials. They explain that this fungal leather takes less time to produce than existing substitutes already on the market, and, unlike some, is 100% biobased.

The researchers will present their results today at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS Spring 2022 is a hybrid meeting being held virtually and in-person March 20-24, with on-demand access available March 21-April 8. The meeting features more than 12,000 presentations on a wide range of science topics.

Cotton is in short supply, and, like petroleum-based textiles and leather, its production is associated with environmental concerns. Meanwhile, plenty of food goes to waste. Akram Zamani, Ph.D., set out to resolve these seemingly unrelated problems with new biobased, sustainable materials derived from fungi. “We hope they can replace cotton or synthetic fibers and animal leather, which can have negative environmental and ethical aspects,” says Zamani, the project’s principal investigator. “In developing our process, we have been careful not to use toxic chemicals or anything that could harm the environment.”

Just like humans, fungi need to eat. To feed the organisms, the team collected unsold supermarket bread, which they dried and ground into breadcrumbs. The researchers mixed the breadcrumbs with water in a pilot-scale reactor and added spores of Rhizopus delemar, which can typically be found on decaying food. As this fungus fed on the bread, it produced microscopic natural fibers made of chitin and chitosan that accumulated in its cell walls. After two days, the scientists collected the cells and removed lipids, proteins and other byproducts that could be used in food or feed. The remaining jelly-like residue consisting of the fibrous cell walls was then spun into yarn, which could be used in sutures or wound-healing textiles and perhaps in clothing.

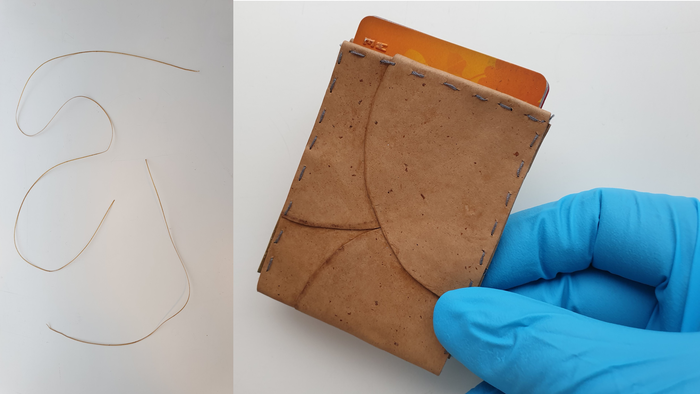

Alternatively, the suspension of fungal cells was laid out flat and dried to make paper- or leather-like materials. The first prototypes of fungal leather the team produced were thin and not flexible enough, says Zamani, who is at the University of Borås in Sweden. Now the group is working on thicker versions consisting of multiple layers to more closely mimic real animal leather. These composites include layers treated with tree-derived tannins — which give softness to the structure — combined with alkali-treated layers that give it strength. Flexibility, strength and glossiness were also improved by treatment with glycerol and a biobased binder. “Our recent tests show the fungal leather has mechanical properties quite comparable to real leather,” Zamani says. For instance, the relation between density and Young’s modulus, which measures stiffness, is similar for the two materials.

While some other fungal leathers have already reached the market, little information about their production has been published, and their properties don’t yet match real leather, according to Zamani. From what she can ascertain, the commercial products are made from harvested mushrooms or from fungus grown in a thin layer on top of food waste or sawdust using solid state fermentation. Such methods require several days or weeks to produce enough fungal material, she notes, whereas her fungus is submerged in water and takes only a couple of days to make the same amount of material. A few other researchers are also experimenting with submerged cultivation but at a much smaller scale than her group’s efforts.

In addition, some of the fungal leathers on the market contain environmentally harmful coatings or reinforcing layers made of synthetic polymers derived from petroleum, such as polyester. That contrasts with the University of Borås team’s products, which consist solely of natural materials and will therefore be biodegradable, Zamani expects.

Her team is working to further refine their fungal products. They also recently began testing other types of food waste, including fruits and vegetables. One example is the mass left after juice is pressed from fruit. “Instead of being thrown away, it could be used for growing fungi,” Zamani says. “So we are not limiting ourselves to bread, because hopefully there will be a day when there isn’t any bread waste.”

The researchers acknowledge support and funding from Vinnova. A video on Zamani’s research is available from the University of Borås here.

A recorded media briefing on this topic will be posted Wednesday, March 23, by 10 a.m. Eastern time at www.acs.org/acsspring2022briefings.

ACS Spring 2022 will be a vaccination-required and mask-recommended event for all attendees, exhibitors, vendors, and ACS staff who plan to participate in-person in San Diego, CA. For detailed information about the requirement and all ACS safety measures, please visit the ACS website.

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive press releases from the American Chemical Society, contact [email protected].

Note to journalists: Please report that this research was presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.

Follow us: Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram

Title

Sustainable fungal textiles and paper-like materials from food waste

Abstract

Shortage of cotton and environmental concerns of petroleum-based textiles have resulted in large demand for sustainable alternatives. At the same time food waste causes enormous economic and environmental loss. This research presents a novel approach for re-use of food waste through its bioconversion to textile materials. The filamentous fungus Rhizopus delemar was grown on food waste in an airlift bioreactor in a scalable submerged cultivation process. The mycelium’s cell wall, containing chitin and chitosan, was isolated from the harvested fungal biomass and subjected to a wet spinning process to align the fungal microfibers and develop monofilament yarns. From the mechanical strength perspective, the highest tensile strength and Young’s modulus was 118 MPa and 6.4 GPa, respectively. Treatment of the fibers with glycerol resulted in significant improvement in the fiber flexibility and resulted in the highest elongation at break of 15.8%. The monofilaments exhibited antibacterial properties and biocompatibility. Furthermore, the fungal microfibers were wet-laid to form biocompatible paper-like materials with tensile strengths of up to 71 MPa and Young’s modulus of up to 3.4 GPa. Additionally, a tanning process was performed on fungal microfibers, and leather-like materials were prepared through wet-laying and post-treatments. The fungal leather exhibited similar Young’s modulus vs. density behavior as natural leathers.