Credit: Jason Travers, Exceptional Children

LAWRENCE — In education circles, it is widely accepted that minorities are overrepresented in special education. New research from the University of Kansas has found, in terms of autism, minorities are widely underrepresented in special education. The underrepresentation varies widely from state to state and shows that students from all backgrounds are not being identified accurately, resulting in many students, especially those from minority backgrounds, not receiving services that are crucial to their education.

Jason Travers, associate professor of special education at KU, led a study that analyzed autism identification rates for every state. Travers then compared the percentage of minority students with autism to the percentage of white students with autism in each state and compared rates for each group to the rate for white students with autism in California. The analyses looked at data from 2014, which was three years after federal regulations changed from five racial categories to seven. It was also the most current year for data analyzed by the Centers for Disease Control on the prevalence of autism. Travers' research had previously shown underrepresentation of minorities in autism, but the change warranted a renewed look.

"A considerable change in demographic reporting happened at the federal all the way down to the local level," Travers said. "So individual schools had to change their reports and send them to the state, who then sent them to the federal government. So, for several years we've had an incomplete picture of autism identification rates."

The change allowed schools to report students, including those with autism, as belonging to "two or more races" for the first time, and also established two separate categories for Pacific Islander and Asian students who previously were reported as one group. The report, co-authored with Michael Krezmien of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, was published in the journal Exceptional Children.

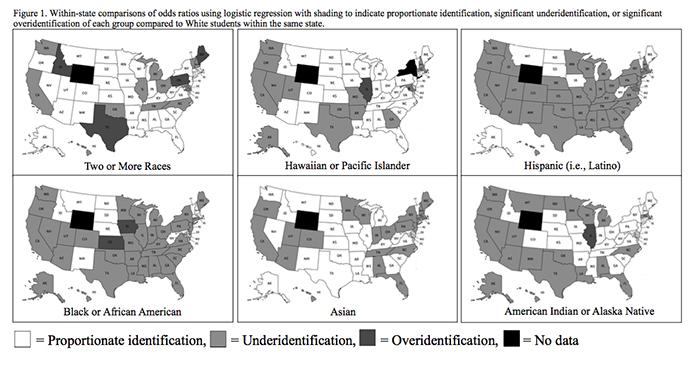

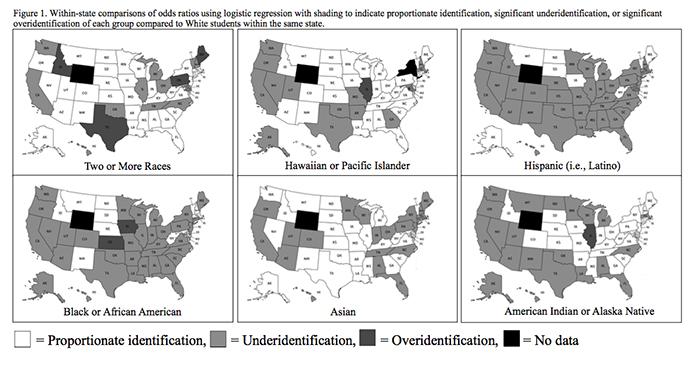

The data showed dramatic underrepresentation of minority students with autism in the majority of states, especially for African-American and Hispanic students. Forty states underidentified African-American students with autism when compared to white students in the same state, and 43 states underidentified Hispanic students. When the rate for each minority was compared to the rate for white students with autism in California, the data showed nearly every state underidentified minority students with autism.

Not one state had higher percentages of students from those minority groups identified at higher rates than whites, and no state had African-American or Hispanic students listed at the same percentage of white students with autism in California.

"We suspected that, although the U.S. has a similar amount of Hispanic and African-American people, children with autism in both groups would be underrepresented compared to white students. We also didn't know what the rates would be for students identified as being two or more races, Pacific Islander and Asian students due to these being new federal reporting categories," Travers said.

California was used as a comparison for the other states as it is both the largest state by population and widely considered to have outstanding infrastructure for identifying and serving students with autism. The identification rate in California also was similar to the prevalence rate recently reported by the CDC. As the largest state, it is also the state least vulnerable to statistical fluctuation in data, Travers said.

While underrepresentation of minority students with autism was common, there was wide variance from state to state. For example, in Kansas, African-American students were overrepresented. Iowa was the only other state where that was also the case. No states overidentified Hispanic students, and 42 states underidentified them.

"Almost every state in the nation underidentified African-Americans. We're not sure why that happened, but it did," Travers said. "Another notable finding about Kansas is Hispanic students continued to be underidentified."

Students of two or more races were proportionately identified in the majority of states, though a handful showed both under and overidentification. Forty-six of 49 states, including the District of Columbia, had a lower percentage of white students identified than California. No states identified Asian students with autism at the same percentage as white students in California, the comparison group. For its part, California significantly underidentified every minority group when compared with their white peers with autism. Numerous other fluctuations in representation were found in the data as well.

The wide variance of representation shows a number of factors at play. States are identifying minority students with autism in ways different from white students, but also in ways different from those in California, Travers said.

"Some of that just may be statistics, but when you see almost all states identify children with autism at rates that are about or less than half of the rate for white kids in California, that seems pretty concerning," Travers said. "Fundamentally, that means there are kids with autism who are not being identified, and therefore probably aren't receiving the kinds of services we know can help. But there are also specific groups of minority children who are being identified at rates significantly lower than their white peers."

The findings counter the prevailing notion in special education that minority students are overrepresented in special education because the system is being used as a tool of oppression. Instead, it could mean school officials are not identifying minority students with autism due to longstanding concerns about placing too many minority students in special education, at least in terms of autism, Travers said. Worse yet, the problem appears to be nationwide. If the data showed underrepresentation in only a few states or in one geographic region it could reasonably be explained as caused by that states' policies or regional factors. Instead, Travers said, the findings suggest inaccurate autism identification is a more important problem than overrepresentation in special education, and that more must be done to ensure equitable access to specialized treatment.

White students and families traditionally have more access to autism diagnoses and interventions, which can be expensive, Travers said. However, he doesn't believe white students are overrepresented in the autism category. Instead, Travers suspects well-intentioned school leaders may be inadvertently denying minority students an autism eligibility due to concerns about exacerbating the widely perceived problem of minority overrepresentation. Travers hopes to study whether students are being accurately identified within their states in future research. He also hopes to determine if certain factors can more accurately predict autism identification by using a more sophisticated analysis of regional, school district, school and student-level factors.

For now, the data shows that underidentification of minority students with autism is happening across the country and that a better understanding of accurate identification is needed.

"These trends are prevalent across the country," Travers said. "I think the focus on overrepresentation of minority students in special education overlooks the more important issue of accurate identification. The field should focus on ensuring accurate identification of minority students with disabilities, including those who need autism-specific services."

###

Media Contact

Mike Krings

[email protected]

785-864-8860

@KUNews

http://www.news.ku.edu