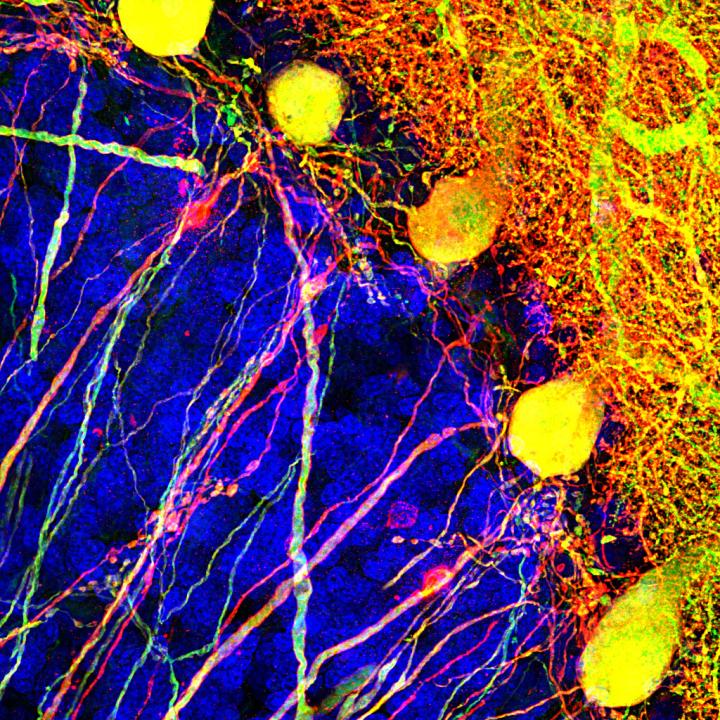

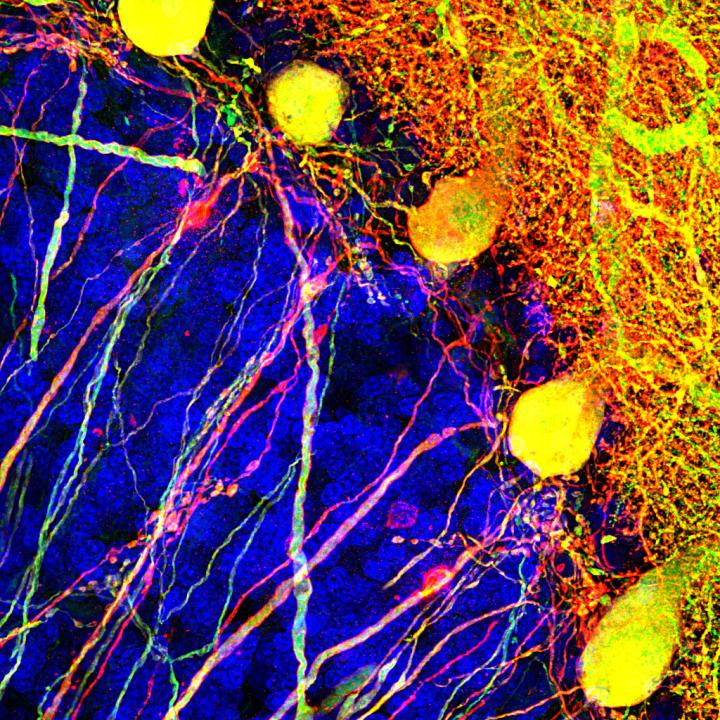

Credit: Horwitz Lab/UW Medicine Seattle

UW Medicine researchers have developed a technique for inserting a gene into specific cell types in the adult brain in an animal model.

Recent work shows that the approach can be used to alter the function of brain circuits and change behavior. The study appears in the journal Neuron in the NeuroResources section.

Gregory Horwitz, associate professor of physiology and biophysics at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, led the research team. He said that the approach will allow scientists to better understand what roles select cell types play in the brain's complex circuitry.

Researchers hope that the approach might someday lead to developing treatments for conditions, such as epilepsy, that might be curable by activating a small group of cells

"The brain is made up of a mix of many cell types performing different functions. One of the big challenges for neuroscience is finding ways to study the function of specific cell types selectively without affecting the function of other cell types nearby," Horwitz said. "Our study shows it is possible to selectively target a specific cell type in an adult brain using this technique and affect behavior nearly instantly."

In their study, Horowitz and his colleagues at the Washington National Primate Research Center in Seattle inserted a gene into cells in the cerebellum, a small structure located at the back of the brain and tucked under the brain's larger cerebrum.

The cerebellum's primary function is controlling motor movements. Disorders of the cerebellum generally lead to often disabling loss of coordination. Recent research suggests the cerebellum may also be important in learning and may be involved in such conditions as autism and schizophrenia.

The cells the scientists selected to study are called Purkinje cells. These cells, named after their discoverer, Czech anatomist Jan Evangelista Purkinje, are some of the largest in the human brain. They typically make connections with hundreds of other brain cells.

"The Purkinje cell is a mysterious cell," said Horwitz. "It's one of the biggest and most elaborate neurons and it processes signals from hundreds of thousands of other brain cells. We know it plays a critical role in movement and coordination. We just don't know how."

The gene they inserted, called channelrhodopsin-2, encodes for a light-sensitive protein that inserts itself into the brain cell's membrane. When exposed to light, it allows ions – tiny charged particles – to pass through the membrane. This triggers the brain cell to fire.

The technique, called optogenetics, is commonly used to study brain function in mice. But in these studies, the gene must be introduced into the embryonic mouse cell.

"This 'transgenic' approach has proved invaluable in the study of the brain," Horwitz said. "But if we are someday going to use it to treat disease, we need to find a way to introduce the gene later in life, when most neurological disorders appear."

The challenge for his research team was how to introduce channelrhodopsin-2 into a specific cell type in an adult animal. To achieve this, they used a modified virus that carried the gene for channelrhodopsin-2 along with segment of DNA called a promoter. The promoter stimulates the cell to start expressing the gene and make the channelrhodopsin-2 membrane protein. To make sure the gene was expressed only by Purkinje cells, the researchers used a promoter that is strongly active in Purkinje cells, called L7/Pcp2."

In their paper, the researchers reported that by painlessly injecting the modified virus into a small area of the cerebellum of rhesus macaque monkeys, the channelrhodopsin-2 was taken up exclusively by the targeted Purkinje cells. The researchers then showed that when they exposed the treated cells to light through a fine optical fiber, they were able stimulate the cells to fire at different rates and affect the animals' motor control.

Horwitz said that it was the fact that Purkinje cells express L7/Pcp2 promoter at a higher rate than other cells that made them more likely to produce the channelrhodopsin-2 membrane protein.

"This experiment demonstrates that you can engineer a viral vector with this specific promoter sequence and target a specific cell type," he said. "The promoter is the magic. Next, we want to use other promoters to target other cell types involved in other types of behaviors."

###

Horwitz coauthors were: lead author Yasmine El-Shamayleh, a postdoctoral fellow; Yoshiko Kojima, an acting instructor; and Robijanto Soetedjo, a UW School of Medicine research associate professor of physiology and biophysics. All are researchers at the Washington National Primate Research Center.

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health grants to the researchers; an NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs grant to the Washington National Primate Research Center, and a National Eye Institute Center Core Grant for Vision Research to the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Media Contact

Michael McCarthy

[email protected]

206-543-3620

@hsnewsbeat

http://hsnewsbeat.uw.edu/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.002

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag