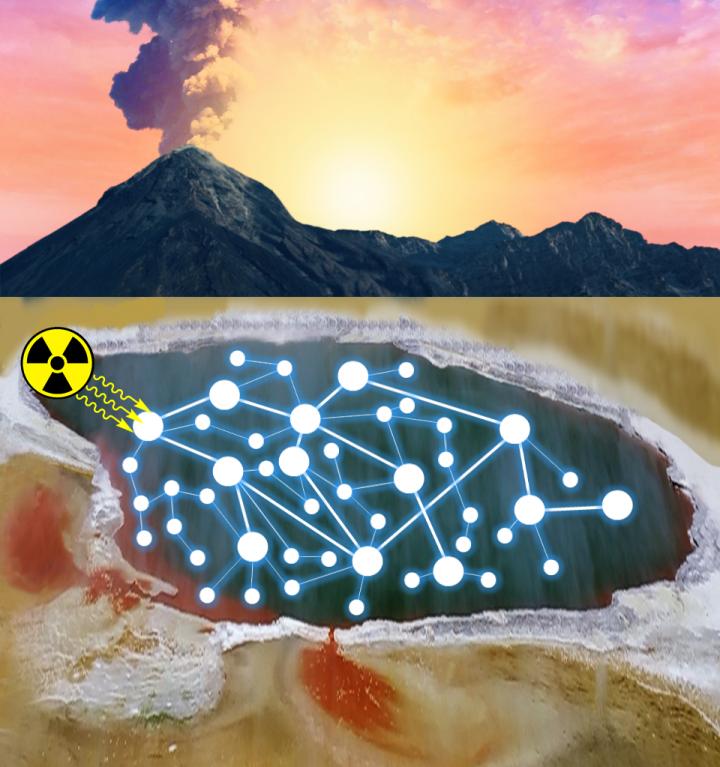

Credit: Ruiqin Yi, ELSI

Researchers have long sought to understand the origins of life on Earth. A new study conducted by scientists at the Institute for Advanced Study, the Earth-Life Science Institute (ELSI), and the University of New South Wales, among other participating institutions, marks an important step forward in the effort to understand the chemical origins of life. The findings of this study demonstrate how “continuous reaction networks” are capable of producing RNA precursors and possibly ultimately RNA itself–a critical bridge to life. A link to the paper, published by Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, can be found here: https:/

While many of the mechanisms that propagate life are well understood, the transition from a prebiotic Earth to the era of biology remains shrouded in mystery. Previous experiments have demonstrated that simple organic compounds can be produced from the reactions of chemicals understood to exist in the primitive Earth environment. However, many of these experiments relied on coordinated experimenter interventions. This study goes further by employing a model that is minimally manipulated to most accurately simulate a natural environment.

To conduct this work, the team exposed a mixture of very simple small molecules–common table salt, ammonia, phosphate, and hydrogen cyanide–to a high energy gamma radiation source. These conditions simulate radioactive environments made possible by naturally occurring radioactive minerals, which were likely much more prevalent on early Earth. The team also allowed the reactions to intermittently dry out, simulating evaporation in shallow puddles and beaches. These experiments returned a variety of compounds that may have been important for the origins of life, including precursors to amino acids and other small compounds known to be useful for producing RNA.

The authors use the term “continuous reaction network” to describe an environment in which intermediates are not purified, side products are not removed, and no new reagents are added after the initial starting materials. In other words, the synthesis of molecules occurs in a dynamic environment in which widely varied compounds are continuously being formed and destroyed, and these products react with each other to form new compounds.

Jim Cleaves, frequent IAS visitor and ELSI professor, stated, “These types of continuous reaction networks may be quite common in chemistry, but we are only now beginning to build the tools to detect, measure, and understand them. There is a lot of exciting work ahead.”

Future work will focus on mapping out reaction pathways for other chemical substances and testing whether further cycles of radiolysis followed by dry-down can generate higher order chemical products. The team believes these models can help to determine what primitive planetary environments are most conducive to the formation of complex molecules. These studies could in turn help other scientists identify the best places to look for life beyond Earth.

###

About the Institute

The Institute for Advanced Study is one of the world’s foremost centers for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. Located in Princeton, N.J., the IAS is dedicated to independent study across the sciences and humanities. Founded in 1930 with the motto “Truth and Beauty,” the Institute is devoted to advancing the frontiers of knowledge without concern for immediate application. From founding IAS Professor Albert Einstein to the foremost thinkers of today, the IAS enables bold, nonconformist, field-leading research that provides long-term utility and new technologies, leading to innovation and enrichment of society in unexpected ways.

Each year, the Institute welcomes more than 200 of the world’s most promising researchers and scholars who are selected and mentored by a permanent Faculty, each of whom are preeminent leaders in their fields. Comprised of four Schools–Historical Studies, Mathematics, Natural Sciences, and Social Science–IAS has produced an astounding record of introducing new understanding and is responsible for undeniable progress across disciplines and generations, from the development of one of the first stored-program computers to the establishment of art history as a discipline in the United States. Among its present and past Faculty and Members are 34 Nobel Laureates, 42 of the 60 Fields Medalists, and 19 of the 22 Abel Prize Laureates, as well as many MacArthur Fellows and Wolf Prize winners.

Media Contact

Lee Sandberg

[email protected]

Original Source

http://www.