Credit: (c) Photo: Christian Burkert

Whether or not we consciously perceive the stimuli projected onto our retina is decided in our brain. A recent study by the University of Bonn shows how some signals dissipate along the processing path to conscious perception. This process begins at rather late stages of signal processing. By contrast, in earlier stages there is hardly any difference in the reaction of neurons to conscious and unconscious stimuli. The paper is published in Current Biology.

The researchers are basing their study on a well-known phenomenon: When presented with two images in rapid succession, humans can only consciously perceive the second one if there is sufficient time between the two presentations. In this study the participants saw a series of pictures on a computer screen, where each image was presented for just over one tenth of a second. Before each series the participants were instructed to pay special attention to two target stimuli, and they were asked if those images were part of the series afterwards.

"We varied the time between the two attended images," explained Dr. Thomas P. Reber, one of the authors. "Sometimes they were presented directly one after the other, and sometimes there was one or even several images between them. Whenever both target stimuli were presented in close succession, participants reported in a little under half of the cases to only have seen the first one. This allowed us to compare conscious and unconscious processing of identical picture presentations."

A look inside the epileptic brain

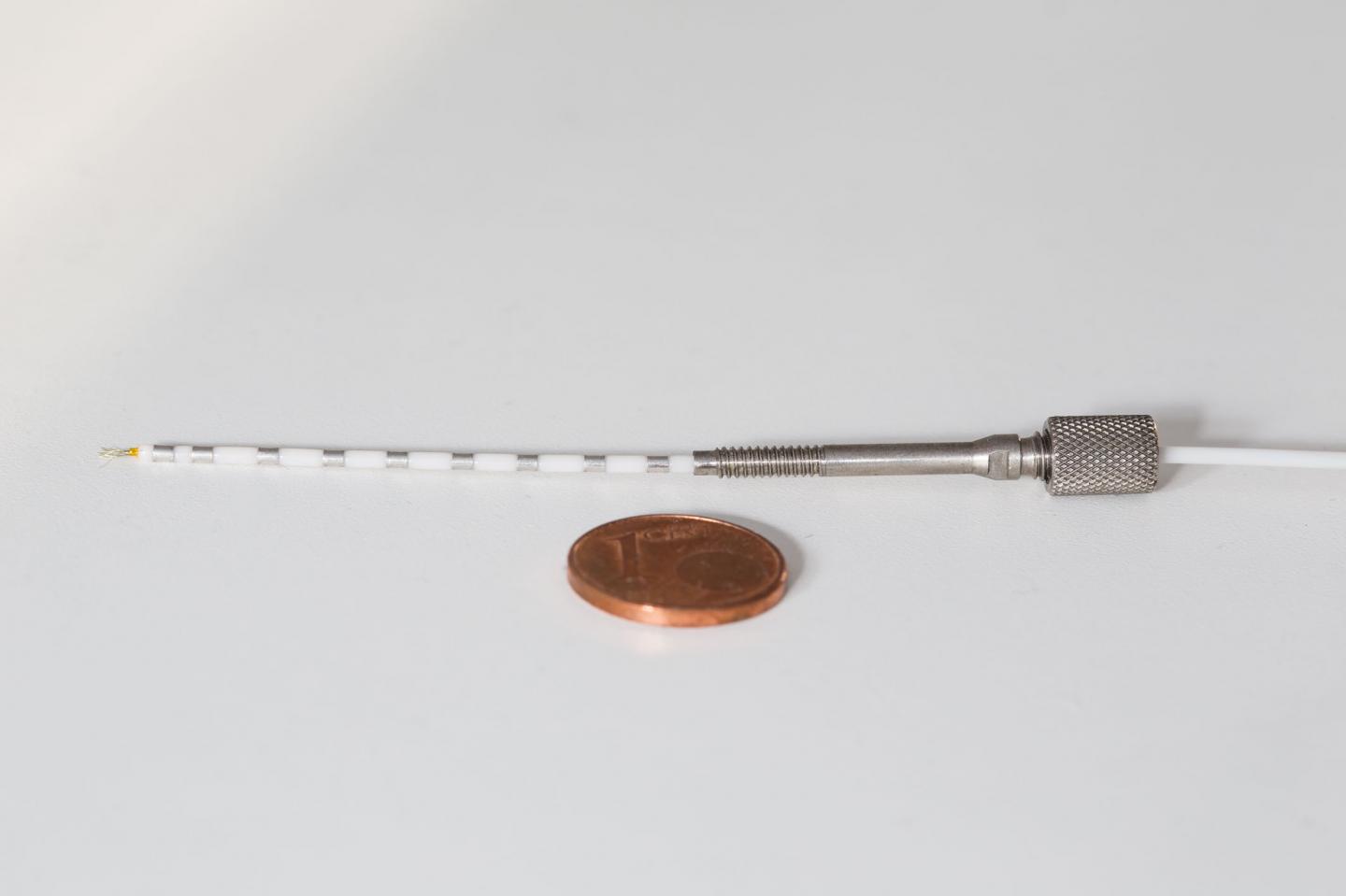

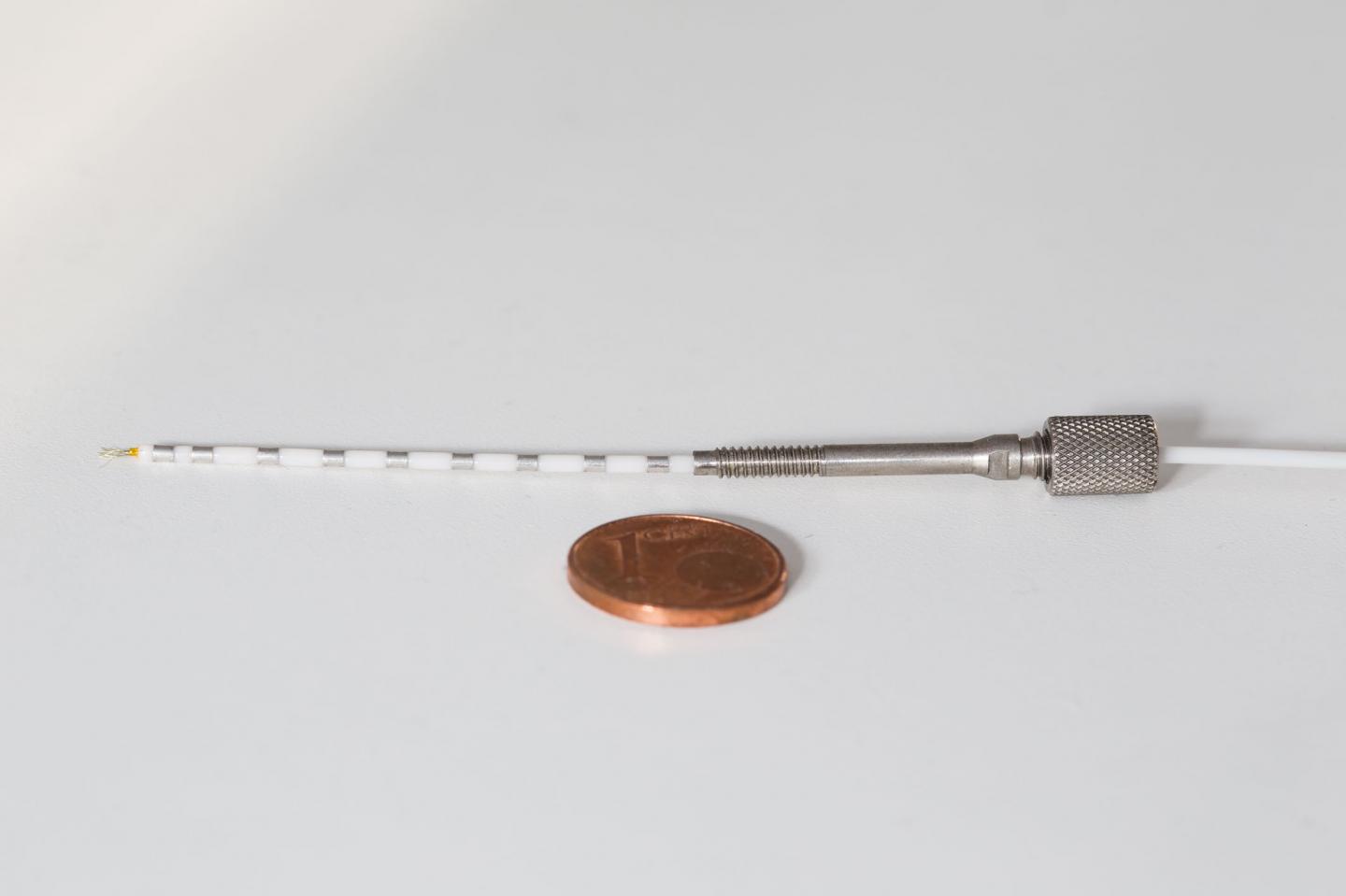

Reber works in the Department of Epileptology at the University Hospital of Bonn – one of the biggest epilepsy centers in Europe. Among its patients are severe cases of so-called medial temporal lobe epilepsy. A last resort for them can be the removal of brain tissue triggering epileptic seizures. In some cases, electrodes are implanted into the patient's brain to localize the epileptic focus for later resection. As a byproduct, researchers can make use of this circumstance to virtually 'watch' the patients think.

This was also the case during the latest study – the 21 participants were all epilepsy patients with special microelectrodes implanted in the temporal lobe. "That way we were able to measure the reaction of single nerve cells to visual stimuli," explains Dr. Florian Mormann, Professor of Cognitive and Clinical Neurophysiology. "We wanted to investigate how the processing of images differs depending on whether they have been perceived consciously or not."

Seen: Yes. Consciously perceived: No.

When an image is projected onto the retina, the respective information is transmitted along the optic nerve to the so-called visual cortex at the back of the skull. From here the signal branches out and part of it is projected back towards the forehead. The measurements show how the electric impulses change along this pathway. "In the back part of the temporal lobe, where the earlier processing steps take place, there are hardly any differences between consciously and unconsciously processed images", says Dr. Reber. "The distinction of 'conscious' and 'unconscious' follows significantly further down the processing stream than many researchers have been suspecting: On their way to the frontal areas of the temporal lobe, the impulses in response to unconsciously perceived images weaken, and they occur with an increasing delay."

The eye registers an image and generates a corresponding signal. However, in some cases this signal seems to be "disintegrating" before reaching the viewer's consciousness, in this case resulting in the patient not perceiving the image. "It is remarkable," says Reber, "We can show that the patient has been presented with a certain image — even if they have no conscious perception of it." This basic research paper provides new insights on the border between conscious and unconscious perception.

###

Publication: Thomas P. Reber, Jennifer Faber, Johannes Niediek, Jan Boström, Christian E. Elger, Florian Mormann: Single-neuron correlates of conscious perception in the human medial temporal lobe; Current Biology; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.025

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Dr. Florian Mormann

Klinik für Epileptologie

Universitätsklinikum Bonn

Tel. 0228/28715738

eMail: [email protected]

Dr. Thomas Reber

Klinik für Epileptologie

Universitätsklinikum Bonn

Tel. 0228/28715742

eMail: [email protected]

Media Contact

Prof. Dr. Dr. Florian Mormann

[email protected]

49-228-287-15738

@unibonn

http://www.uni-bonn.de

Related Journal Article

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.08.025