Credit: Intermountain Medical Center.

National guidelines assume that all patients who're diagnosed with clinical sepsis in an emergency department will be admitted to the hospital for additional care, but new research has found that many more patients are being treated and released from the ED for outpatient follow-up than previously recognized.

Despite the finding that about 16 percent of sepsis patients who are diagnosed in the emergency department are not being admitted to the hospital, but are treated in the ED and released for outpatient management, researchers at Intermountain Medical Center in Salt Lake City found that these patients are still experiencing good outcomes.

"We found that many more emergency department patients with sepsis are discharged from the ED than previously recognized, but by and large these patients had fairly good outcomes," said principal investigator Ithan Peltan, MD, MSc, a pulmonary and critical care medicine specialist and researcher from Intermountain Medical Center in Salt Lake City, which is part of the Intermountain Healthcare system.

Researchers presented results from the study of nearly 16,000 sepsis patientsthis week at the American Thoracic Society's annual international conference in San Diego.

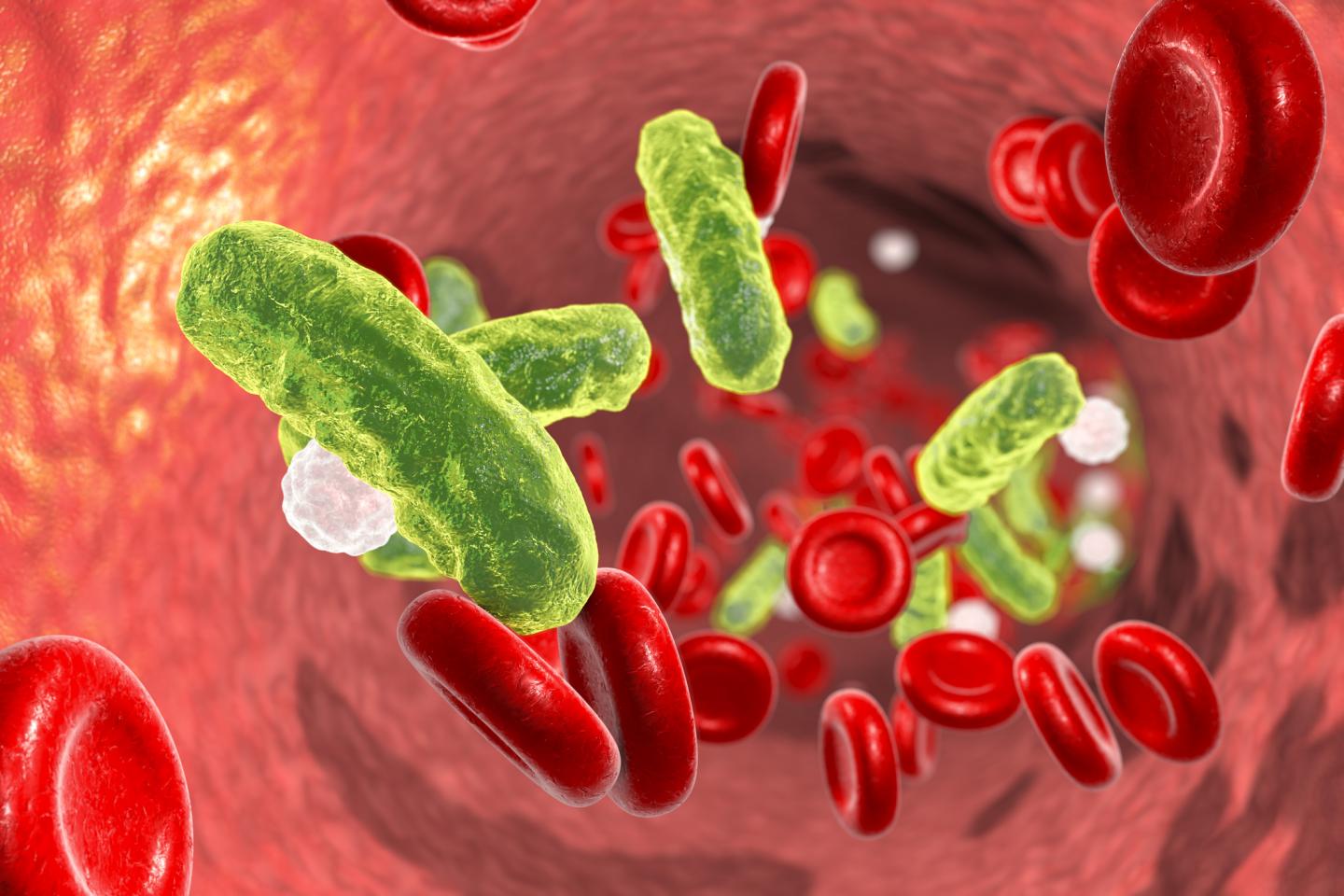

Sepsis is a life-threatening response to an infection. It occurs when chemicals released into the bloodstream to fight an infection trigger inflammatory responses throughout the body, which can trigger a cascade of changes that can damage multiple organ systems and cause them to fail. Without timely treatment, sepsis can rapidly cause tissue damage, organ failure, and death.

"Sepsis is a common and deadly problem among patients who come to the emergency department," said Dr. Peltan. "While widely-accepted guidelines assume all sepsis patients will be admitted to the hospital, we found that about 16 percent are in fact discharged from the ED for outpatient management. Our research looked at sepsis patients who were discharged and investigated their outcomes."

The sepsis disease process isn't fully understood, and treatment is often complicated, which is one of the reasons guidelines have assumed sepsis patients need to be admitted to the hospital. However, the Intermountain Healthcare research suggests that physicians can identify a subset of sepsis patients who do well with outpatient management.

"Outpatient management of sepsis is likely not automatically 'wrong.' But wide variation in care provided by different physicians suggests there's room to identify criteria and develop and test tools clinicians can use to guide and optimize sepsis triage decisions," said Dr. Peltan.

For the study, researchers searched Intermountain Healthcare's Enterprise Data Warehouse, which is one of the nation's largest depositories of clinical data, at two referral hospitals and two community hospitals in Utah between July 2013 and January 2017.

Researchers identified 15,832 adult ED patients who met clinical sepsis criteria. After excluding repeat ED visits, trauma patients, patients who left the ED against medical advice or on hospice, or those who passed away in the ED, 12,002 of 13,419 eligible ED sepsis patients were included in the analysis. Patients who transferred to another acute care facility were considered to be admitted, whereas transfers to non-acute care in skilled nursing or psychiatric facilities were classified as discharges.

Unsurprisingly, patients who were discharged were much less ill than admitted patients. However, after accounting for illness severity and other factors, Dr. Peltan and his team found that discharged sepsis patients had about the same chance of dying in the following 30 days as admitted patients. Some ED physicians admitted all, or almost all, of the patients they treated, while others discharged up to 39% of their sepsis patients.

Additionally, the researchers found that 65% of sepsis patients who were treated and released from the ED were women, compared to 35% of the male patients who were admitted to the hospital. Researchers plan more to examine this and other potential disparities more closely in their next study. An initial hypothesis is that women may come to the ED earlier in their illness, meaning they're less sick.

"Physicians seem to do a good job of knowing who can be discharged," said Dr. Peltan. "However, there was quite a bit of variation between physicians regarding how many of their patients get discharged, which suggests it may be important to give clinicians guidance to ensure patients who need it are admitted to the hospital, and to identify patients who can be considered for outpatient management and potentially avoid the inconvenience, expense, and risks of hospitalization."

###

Other researchers involved in the study are: Nathan C. Dean, MD; Joseph R. Bledsoe, MD; Todd L. Allen, MD; Emily L. Wilson, MS; Matthew M. Samore, MD; and Samuel M. Brown, MD, MS.

The study was partially funded by donors to the Intermountain Research and Medical Foundation.The Foundation provides seed grant money for worthy research projects, such as this one, that lead to clinical applications.

Media Contact

Jess C. Gomez

[email protected]

801-718-8495

@IntermtnMedCtr

http://www.ihc.com