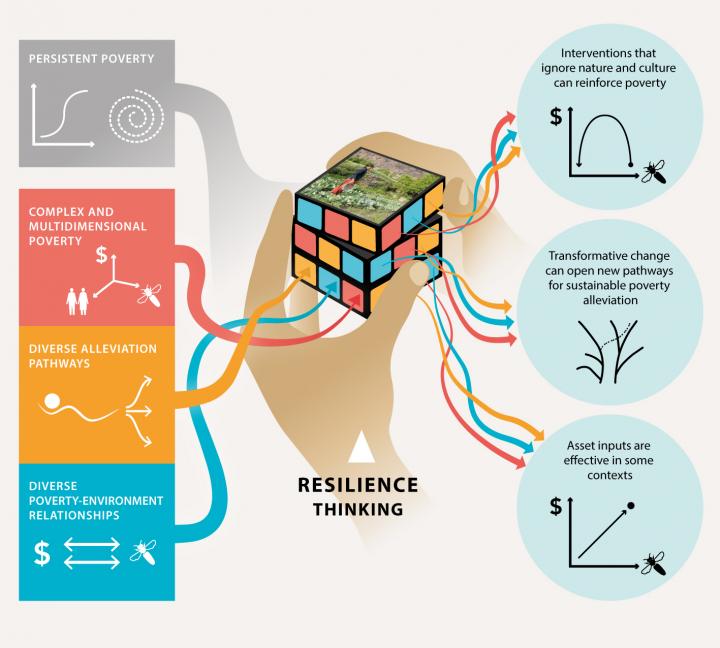

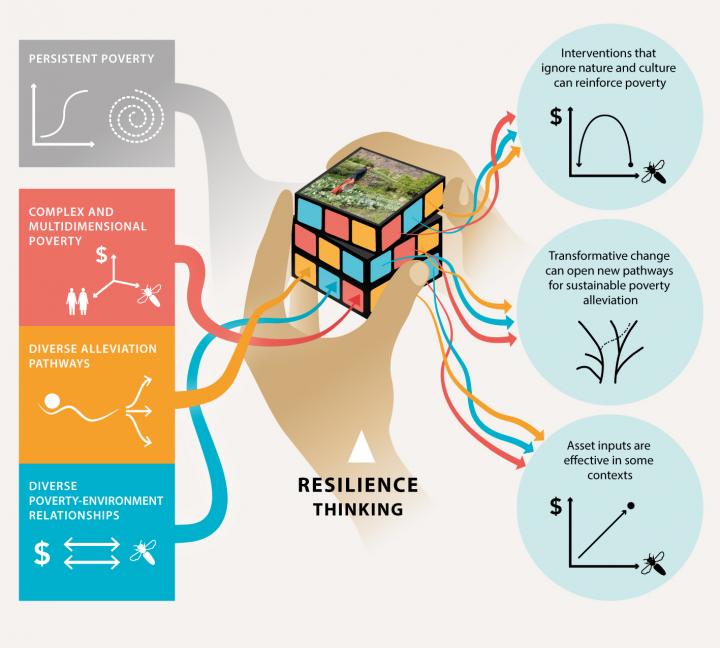

Credit: Stockholm Resilience Centre. Design: Azote, E. Wikander and E. Wisniewska

Development aid reached a new peak of 142.6 billion USD, according to recent data from the OECD.

Now, in the journal Science Advances (5 May) researchers based in Sweden and Australia call into question a cornerstone of development aid: the "poverty trap" and its "Big Push" solution. This is when aid agencies inject cash for seeds, fertilisers and machinery, for example, into rural economies caught in a vicious cycle of underdevelopment. In theory, this will push these economies "over the barrier" to become better functioning economies.

But for decades a regular criticism levelled at this singular approach is that it can lead to ever-more persistent poverty in some places because culture and nature are ignored.

Co-lead author Jamila Haider at the Stockholm Resilience Centre says, "For the first time, we provide a way to extend poverty-trap thinking to more fully include the links between financial well-being, nature and culture."

"This new approach makes it difficult for development agencies to ignore a broader range of options and solutions."

The research could inform better integration of the UN's Sustainable Development Goals.

Co-lead author Steven Lade also at Stockholm Resilience Centre says, "The goals call for doubling agricultural productivity by 2030. Ignoring cultural and environmental factors could increase the risk of poverty traps."

With 78% of the world's poorest people living in rural areas, development aid is often targeted at quick-fix financial and technological farming solutions. The "Big Push" – one of the earliest theories of development economics — is still a popular one-size-fits-all approach, despite its known limitations. Development agencies often encourage farmers to grow single cash crops, or monocultures, such as GM cotton in India, that they can sell to rise out of poverty – with mixed results.

While successful in many places, it can lead to deforestation, or nitrogen and phosphorus pollution to name a few environmental consequences. In some instances, it has created a cycle of poverty where "improved" seed varieties fail due to neglect of local environmental conditions and culture, leaving the land in a worse condition than before, and losing valuable knowledge — reinforcing the poverty trap.

The team's new approach classifies three types of solutions to alleviate poverty. The first is the standard Big Push "over the barrier". The second is to "lower the barrier", which could include training of farmers to change behavior and practices. These two classifications form the backbone of current aid strategies. The researchers introduce a third classification they call "transform the system".

This is about fundamentally rethinking the intervention strategy. For example, encouraging a farmer to devote a portion of his or her intensively-farmed land to local crops maintained through traditional practice to maintain resilient seed varieties.

Haider says, "If poverty in an area is causing environmental degradation then maybe a big push will work. But if the land has been managed sustainably for generations then development agencies need an approach that takes that knowledge into consideration."

"This seems obvious, but intervention strategies can become blinded by powerful yet simplistic economic models. Some communities have remained resilient for generations through, for example, using many traditional seed varieties. We show how development interventions need to vary based on different relationships between poverty and environment."

"These models could be used in development planning to make explicit the available knowledge and assumptions of different cases."

Lade adds, "Rather than increasing production through inputs of physical capital, the transformation delivers increased production due to increases in natural capital and cultural capital."

"This is an alternative approach to analyse investments for intervention. Where risks are high that traditional aid will fail, it gives options to explore and implement alternative strategies that focus on transformation built on historically successful cultural practices to manage the local ecology," he said.

Resilience offers escape from trapped thinking on poverty alleviation. Science Advances. 5 May 2017;3: e1603043

###

Contact details

Co-lead author

Jamila Haider, Stockholm Resilience Centre

[email protected]

+46 701917903

Co-lead author

Steven Lade, Stockholm Resilience Centre

[email protected]

+46 70-191-9523

Media

Owen Gaffney, Stockholm Resilience Centre

[email protected]

Tel: +46 (0) 734604833

2016 OECD Development aid (published 11 April 2017). http://www.oecd.org/newsroom/development-aid-rises-again-in-2016-but-flows-to-poorest-countries-dip.htm

Media Contact

Owen Gaffney

[email protected]

46-734-604-833

http://www.stockholmresilience.org/

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag