LAWRENCE — Researchers from the University of Kansas are helping build an international, multidisciplinary center to monitor pathogens in wild mammals and act as an early warning system for pandemic prediction and prevention.

Credit: PICANTE

LAWRENCE — Researchers from the University of Kansas are helping build an international, multidisciplinary center to monitor pathogens in wild mammals and act as an early warning system for pandemic prediction and prevention.

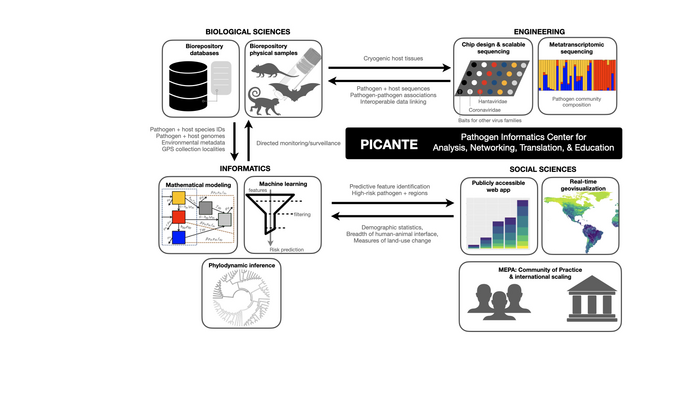

The Pathogen Informatics Center for Analysis, Networking, Translation & Education (PICANTE) will link real-time monitoring of wildlife pathogens to permanent biodiversity archives, including KU’s Biodiversity Institute and Natural History Museum.

PICANTE is supported by an initial $1 million planning grant from the National Science Foundation’s Predictive Intelligence for Pandemic Prevention program. The new center’s approach will be to “detect subtle shifts in pathogen-host-environment systems, to proactively identify threats and predict early signatures of pandemic emergence” through a combination of genomic sequencing, bioinformatics, geovisualization, mathematical modeling and machine learning.

“Traditionally, when a disease emerges in humans, suddenly we care about it — that makes us reactive in the way we sample animals, our environment and even people,” said Jocelyn Colella, Robert W. and Geraldine Wilson Assistant Professor of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at KU and assistant curator of mammals with KU’s Biodiversity Institute, who will head up PICANTE efforts at KU. “That reactive approach is not only ‘too late,’ but it leads to biased sampling that limits our ability to apply cutting-edge computational methods, like machine learning and artificial intelligence, to biodiversity data.”

According to Colella, researchers need to first understand baseline conditions, then monitor changes in those over time.

“This is where including museums can really add to the wildlife component of ‘One Health’ — the idea that the health of humans, animals and their environments are all connected.”

At the outset, PICANTE researchers will focus on hantaviruses in rodents to show the efficacy of their approach. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 833 cases of hantavirus disease in people were reported in the U.S. between 1993 and 2020, following an outbreak in the Southwest in 1993. A larger hantavirus outbreak occurred in Panama around the year 2000 was caused by a different strain of the virus. Today, there are more than 20 recognized strains of hantaviruses found in diverse mammalian hosts from rodents to shrew and bats.

“Our engineering team is developing new technology to affordably and rapidly screen mammal tissues for a suite of different pathogens,” Colella said. “In the meantime, our biologists and social scientists are building models based on tens of thousands of rodent records that have been screened for hantaviruses and human health data to examine how well the environmental space has been sampled and what we need to do better or differently to fill some of those sampling gaps.”

One such scientist is PICANTE researcher Folashade Agusto, associate professor of ecology & evolutionary biology, who will apply mathematical modeling skills to different modeling approaches across fields.

“Here at KU, we are starting by integrating epidemiological and ecological niche modeling approaches to understand the propagation of a pathogen across spatial landscapes, and how that process might be influenced by environmental factors like temperature,” Agusto said. “These models will be coupled with more intricate models of lung infections within a single organism, developed by our New Mexican collaborators, using museum specimens to produce a holistic view of a disease.”

Colella, who will be sampling wild bats in Panama for PICANTE next month with KU doctoral student Ben Wiens, said the new center aims to identify pathogens with high pandemic potential, like hantavirus and other respiratory diseases, then forecast their transmission behavior, based on natural history as well as ongoing field sampling. Doctoral student Marlon Cobos also will work on PICANTE as a postdoc starting this summer.

“Hantaviruses have previously been a health concern in the U.S.,” Colella said. “And through wildlife surveillance, it’s showing up in more species than we previously thought. Information about where and when hanta-positive and negative animals were sampled can inform these new integrative modeling approaches and train artificial-intelligence applications. In theory, our models should only get better as we add specimens to museums. It’s essentially a positive-feedback loop, where we learn about the biosphere and can anticipate what, when and where emergence might happen.”

While PICANTE is based at the University of New Mexico — known for expertise in fungal pathogens and a world-renowned collection of mammalian genomic resources at the Museum of Southwestern Biology — KU will play a key role in the work, providing expertise in mammalian genomics, biorepository capacity building, spatial and epidemiological analyses, as well as new samples from the field.

Both the pilot grant and full proposal, if funded, will support graduate students and postdoctoral researchers to work on zoonotic pathogens and help expand cryogenic infrastructure at KU’s Biodiversity Institute and collaborating institutions.

“The BI has only three liquid nitrogen tanks, or ‘dewars,’ each of which can hold just under 100,000 tissue samples — but with new collaborations in wildlife health we hope to expand that as part of this project,” Colella said.

Other collaborators in PICANTE are based at Los Alamos National Laboratory, New Mexico State University, Gorgas Memorial Institute for Health Studies in Panama and the Center for Research on Health in Latin America (CISeAL) in Ecuador.