The genetic malady known as Fragile X syndrome is the most common cause of inherited autism and intellectual disability. Brain scientists know the gene defect that causes the syndrome and understand the damage it does in misshaping the brain’s synapses — the connections between neurons. But how this abnormal shaping of synapses translates into abnormal behavior is unclear.

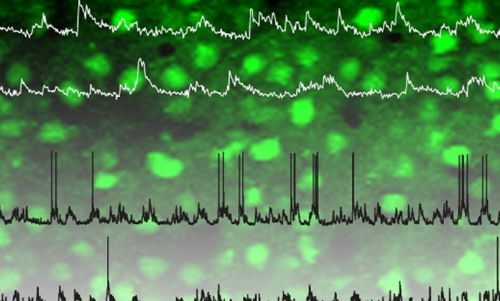

Now, researchers at UCLA believe they know. Using a mouse model of Fragile X syndrome (FXS), they recorded the activity of networks of neurons in a living mouse brain while the animal was awake and asleep. They found that during both sleep and quiet wakefulness, these neuronal networks showed too much activity, firing too often and in sync, much more than a normal brain.

This neuronal excitability, the researchers said, may be the basis for symptoms in children with FXS, which can include disrupted sleep, seizures or learning disabilities. The findings may lead to treatments that could quiet the excessive activity and allow for more normal behavior.

The study results are published in the June 2 online edition of the journal Nature Neuroscience.

According to the National Fragile X Foundation, approximately one in every 3,600 to 4,000 males has the disorder, as does one in 4,000 to 6,000 females. FXS is caused by a mutation in the gene FMR1, which encodes the fragile X mental retardation protein, or FMRP. That protein is believed to be important for the formation and regulation of synapses. Mice that lack the FMR1 gene — and therefore lack the FMRP protein — show some of the same symptoms of human FXS, including seizures, impaired sleep, abnormal social relationships and learning defects.

“We wanted to find the link between the abnormal structure of synapses in the FXS mouse and the behavioral abnormalities at the level of brain circuits. That had not been previously established,” said senior author Dr. Carlos Portera-Cailliau, an associate professor in the departments of neurology and neurobiology at UCLA. ” So we tested the signaling between different neurons in Fragile X mice and indeed found there was abnormally high firing of action potentials — the signals between neurons — and also abnormally high synchrony — that is, too many neurons fired together. That’s a feature that is common in early brain development, but not in the adult.”

“In essence, this points to a relative immaturity of brain circuits in FXS,” added Tiago Gonçalves, a former postdoctoral researcher in Portera-Cailliau’s laboratory and the first author of the study.

The researchers used two-photon calcium imaging and patch-clamp electrophysiology — two sophisticated technologies that allowed them to record the signals from individual brain cells. Abnormally high firing and network synchrony, said Portera-Cailliau, is evidence of the fact that neuronal circuits are overexcitable in FXS.

“That likely leads to aberrant brain function or impairments in the normal computations of the brain,” he said. “For example, high synchrony could lead to seizures; more neurons firing together could cause entire portions of the brain to fire synchronously, which is the basis of seizures.”

And epilepsy, Portera-Cailliau said, is seen in up to 20 percent of children with FXS. High firing rates could also impair the ability of the brain to decode sensory stimuli by causing an overwhelming response to even simple sensory stimuli; this could lead to autism and the withdrawal from social interactions, he noted.

“Interestingly, we found that the high firing and synchrony were especially apparent at times when the animals were asleep,” said Portera-Cailliau. “This is curious because a prominent symptom of FXS is disrupted sleep and frequent awakenings.”

And, he noted, since sleep is important for encoding memories and consolidating learning, this hyperexcitability of brain networks in FXS may interfere with the process of laying down new memories, and perhaps explain the learning disability in children with FXS.

“Because brain scientists know a lot about the factors that regulate neuronal excitability, including inhibitory neurons, they can now try to use a variety of strategies to dampen neuronal excitation,” he said. “Hopefully, this may be helpful to treat symptoms of FXS.”

The next step, said Portera-Cailliau, is to explore whether Fragile X mice indeed exhibit exaggerated responses to sensory stimuli.

“An overwhelming reaction to a slight sound or caress, or hyperarousal to sensory stimuli, could be common to different types of autism and not just FXS,” he said. “If hyperexcitability is the brain-network basis for these symptoms, then reducing neuronal excitability with certain drugs that modulate inhibition could be of therapeutic value in these devastating neurodevelopmental disorders.”

Other authors on the study included Peyman Golshani of UCLA and James E. Anstey of the Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine. The research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NICHD R01HD054453 and NINDS RC1NS068093), the FRAXA Research Foundation, and the Dana Foundation.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by University of California, Mark Wheeler.