Self-organising system enables motile cells to form complex search pattern / Study published in “Nature Physics”

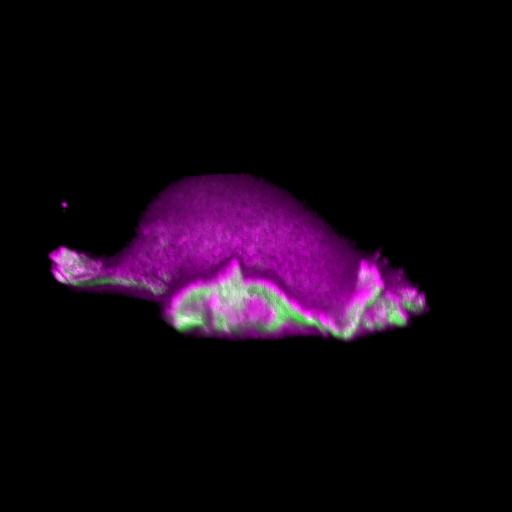

Credit: Isabell Begemann, Milos Galic

When an individual cell is placed on a level surface, it does not keep still, but starts moving. This phenomenon was observed by the British cell biologist Michael Abercrombie as long ago as 1967. Since then, researchers have been thriving to understand how cells accomplish this feat. This much is known: cells form so-called lamellipodia – cellular protrusions that continuously grow and contract – to propel themselves towards signalling cues such as chemical attractants produced and secreted by other cells. When such external signals are missing – as in the observation by Abercrombie – cells begin actively looking for them. In doing so, they use search patterns that can also be observed in sharks, bees or dogs. They transiently move in one direction, stop, wiggle on the spot for a while, and then continue moving in another direction. But how do cells manage to maintain the direction of their movement over a longer period of time?

Researchers at the Cells-in-Motion Cluster of Excellence at the University of Münster (Germany) have now decoded a building block towards answering this question. They discovered that membrane geometry can trigger subsequent lamellipodial cycles: Mechanical forces cause generation of membrane curvature, where certain proteins that recognise this geometry congregate. These proteins, in turn, allow the cell to form the lamellipodia. “The curvature, generated during retraction, already predetermines the growth of the next lamellipodial cycle. This is how the mechanism constantly reactivates itself,” explains biologist Dr Milos Galic, junior research group leader at the Cluster of Excellence, and senior author of the study. When external signals are missing, a cell does not just stop and mark time – it is able to momentarily head in one direction and efficiently patrol its environment. The study has been published in the “Nature Physics” journal.

Methods and further results

The starting point for the study was a surprising observation made while analysing microscopic images. The researchers were investigating how cells formed lamellipodia and, in consequence, how the motion and shape of cells changed. They discovered that the lamellipodia evolved over a wide range of sizes and had very different lifespans. “In the data we couldn’t recognise any recurring pattern in the growth and contraction of lamellipodia,” says biologist Dr Isabell Begemann, who carried out the study as lead author, as part of her doctoral dissertation. The researchers were able to determine, similar to work from other groups, that sites of subsequent lamellipodia extension occurred wherever the cell membrane developed a strong curvature. They therefore hypothesized that a mechanism linked to these curvatures may determine continuous motion cycles and, in consequence, motion persistence.

Biologists, biochemists and physicists worked closely together to investigate this idea. They first developed biosensors in order to label highly curved sites at the cell membrane, and visualised them by various means of high-resolution microscopy. To this end, they connected fluorescent molecules with so-called I-BAR domains. These are banana-shaped regions of proteins whose positively charged side binds the negatively charged cell membrane – but only when the membrane is curved. Taking advantage of these biosensors, the researchers were able to demonstrate that the curvature-sensitive proteins accumulate at sites where the lamellipodium is contracting. Once enriched, these proteins induce protruding forces in the cell via the protein actin, which triggers outgrowth of the lamellipodium. In a next step, the researchers developed a mathematical model that reconstitutes the mechanism, and simulated it on the computer using various parameter combinations. Comparing the predictions derived from the mathematical model with complementing experimental imaging data further strengthened the results found so far.

The researchers found evidence for the presence of the identified motility mechanism in cell culture models, for example in connective tissue cells derived from mice, in human blood vessel cells from the umbilical cord, and also in human immune cells – i.e. a cell type which indeed moves freely within the organism. Finally, the researchers also wanted to know what effects the proposed mechanism had on the motility pattern of a cell. “We down-regulated the I-BAR proteins, enabling us to ‘hack into’ the cell’s self-organisation system,” says Milos Galic. Without the mechanism, the cell does still manage to move, but the search area becomes substantially smaller. Parallel to this mechanism, there are certainly other machineries, which intertwine – but the mechanism has influence on a cell’s motility pattern. The results of the study could, in future, help in answering fundamental questions on processes in organisms involving freely moving cells.

###

Media Contact

Dr. Milos Galic

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.