Many organisms are far more complex than just a single species. Humans, for example, are full of a variety of microbes. Some creatures have even more special connections, though. Acoels, unique marine worms that regenerate their bodies after injury, can form symbiotic relationships with photosynthetic algae that live inside them. These collections of symbiotic organisms are called a holobiont, and the ways that they “talk” to each other are something scientists are trying to understand – especially when the species in question are an animal and a solar-powered microbe.

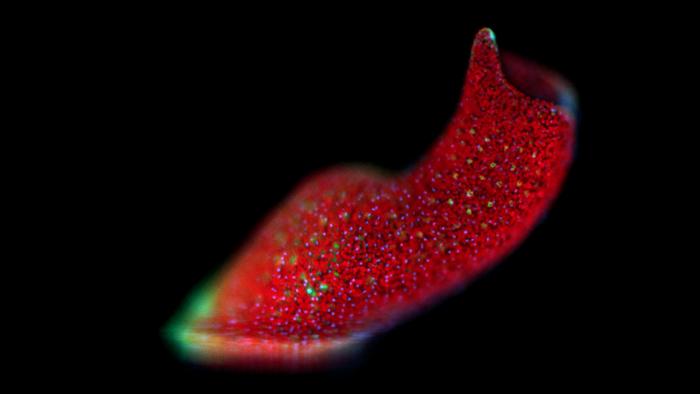

Credit: Dania Nanes Sarfati

Many organisms are far more complex than just a single species. Humans, for example, are full of a variety of microbes. Some creatures have even more special connections, though. Acoels, unique marine worms that regenerate their bodies after injury, can form symbiotic relationships with photosynthetic algae that live inside them. These collections of symbiotic organisms are called a holobiont, and the ways that they “talk” to each other are something scientists are trying to understand – especially when the species in question are an animal and a solar-powered microbe.

Bo Wang, assistant professor of bioengineering in the Schools of Engineering and of Medicine at Stanford, has started to find some answers. His lab, in conjunction with the University of San Francisco, studies Convolutriloba longifissura, a species of acoel that hosts the symbiotic algae Tetraselmis. According to new research, published in Nature Communications, the researchers found that, when C. longifissura regenerates, a genetic factor that takes part in the acoel regeneration also controls how the algae inside of them reacts.

“We don’t know yet how these species talk to each other or what the messengers are. But this shows their gene networks are connected,” said Wang, who is a senior author of the paper.

Splitting worms

Because holobiont is a relatively new concept, scientists still aren’t sure what the nature of some relationships are. The odd name “acoel” is Greek for “no gut,” as the worms have no stomach to speak of. Instead, all things that they eat go directly into their internal tissues – which is also where algae float, photosynthesizing inside their bodies. This relationship provides a safe zone for the algae and extra energy from photosynthesis to the acoel.

“There was no guarantee that there was communication because the algae are not within the acoel’s cells, they’re floating around them,” says James Sikes, a researcher at the University of San Francisco and co-senior author of the paper. Sikes has been working with acoels for about 20 years, and their symbiotic relationship differentiates them from other animals that regenerate, like planarian flatworms and axolotls.

When these acoels reproduce asexually, they first bisect themselves. The head region grows a tail and becomes a new acoel. The tail, however, acts like the mythological Hydra and grows two new heads, which, then, split into two separate animals.

Animal regeneration requires communication across many different cell types, but in this case, it may also involve another organism entirely. Researchers were curious about how the algal colonies inside reacted to this process – in particular, whether they continued to photosynthesize as normal, and if not, what was controlling that? This was especially puzzling as the team found that photosynthesis wasn’t required for acoels to regenerate – they could do it in the dark. But there has to be conversation between the species for their long-term survival.

“Testing if photosynthesis was affected was an adventure. None of us knew what we were doing,” says Dania Nanes Sarfati, lead author of the paper, who was a doctoral student in Wang’s lab and Stanford Bio-X Bowes Fellow. “One of the most exciting things was that we could actually measure algal photosynthesis happening inside the animal.”

In addition, through sequencing, the team was able to differentiate the genes of the two species and figure out which pathways were responding to injury. These measurements helped them realize that the algae inside were undergoing a major reconstruction of their photosynthetic machinery during the regeneration – but the process by which it was being controlled was shocking.

The role of runt

When the results came back, Wang said the unpredictable happened. During regeneration, both the acoel’s regrowth and the algal photosynthesis appeared to be controlled by a common transcription factor in acoels called runt.

In the early stage, right after injury, runt is activated, kicking off the regeneration process. Meanwhile, algal photosynthesis drops off, but there is an upregulation in algal genes associated with photosynthesis – likely to compensate for the loss in photosynthesis due to the split. However, when the researchers knocked down runt, it halted both regeneration and the algal responses.

What’s special about runt is that it’s highly conserved, meaning the same factor is responsible for regeneration in many different organisms, including non-symbiotic acoels. But now it’s clear that instead of just controlling the acoel’s regenerative process, it also controls the communication with another species.

How holobionts communicate

Understanding how partners in symbiotic relationships communicate at the molecular level opens up many new questions for this field of research. “Are there rules of symbiosis? Do they exist?” said Nanes Sarfati. “This research sparks these kinds of questions, which we can link to other organisms.”

Wang believes it introduces more ways of investigating how symbiotic species interact and couple with each other to form holobionts. Some of these interactions could be potentially driven by chemicals, proteins, or environmental factors. But more concerningly, these interactions are now becoming vulnerable points under the challenge of climate change, causing symbiotic partners to separate. Sikes highlighted that he, Wang, and Nanes Sarfati all began from the animal side of the symbiotic relationship but realized that algae respond to host injury as well, potentially sparking similar questions in other systems.

“We often assume we know a lot, but we’re humbled when we look at different species,” Wang said. “They can do things in completely unexpected ways, which highlights the need to study more organisms and is becoming possible with technology.”

Additional Stanford co-authors include former graduate student Yuan Xue, PhD ‘21; PhD student Eun Sun Song; Stephen Quake, the Lee Otterson Professor of Bioengineering in the Schools of Engineering and Medicine and professor of applied physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences; and Adrien Burlacot, assistant professor (by courtesy) of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

Burlacot is also a principal investigator at the Carnegie Institution for Science. Quake is also co-president of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, and a member of Stanford Bio-X, the Cardiovascular Institute, the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance, the Stanford Cancer Institute, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Wang is also a member of Bio-X and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute.

This research was funded by a Bio-X Bowes Fellowship, a Stanford Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship, the Beckman Young Investigator Program, the Carnegie Institution for Science, and the National Institutes of Health.

Journal

Nature Communications

DOI

10.1038/s41467-024-48366-2

Article Publication Date

13-May-2024