[Vienna, April 15 2024] — A “rapid and far-reaching change” is necessary to prevent catastrophic climate change, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). “However, the transformation of the economy towards climate neutrality always involves a certain amount of economic stress — some industries and jobs disappear while others are created,” explains Johannes Stangl from the Complexity Science Hub (CSH). When it comes to climate policy measures, how can economic damage be minimized?

Credit: Complexity Science Hub

[Vienna, April 15 2024] — A “rapid and far-reaching change” is necessary to prevent catastrophic climate change, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). “However, the transformation of the economy towards climate neutrality always involves a certain amount of economic stress — some industries and jobs disappear while others are created,” explains Johannes Stangl from the Complexity Science Hub (CSH). When it comes to climate policy measures, how can economic damage be minimized?

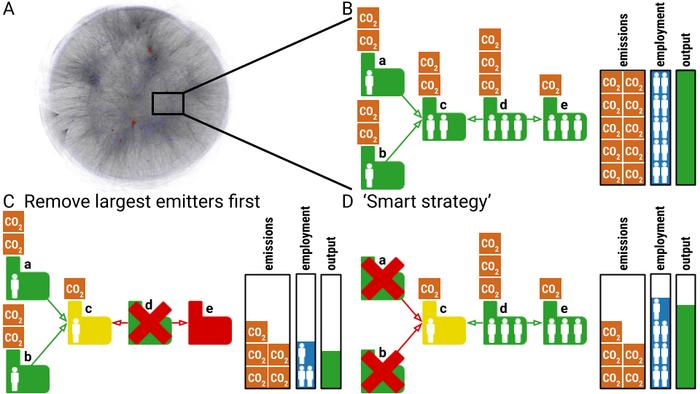

A CSH team has developed a new method to help solve this problem. “To understand how climate policy measures will affect a country’s economy, it’s not sufficient to have data on carbon dioxide emissions. We must also understand the role that companies play in the economy,” says Stangl, one of the co-authors of the study recently published in Nature Sustainability.

CO2 emissions reduced by 20%

The researchers used a data set from Hungary that includes almost 250,000 companies and over one million supplier relationships, virtually representing the entire Hungarian economy. They examined what a country’s entire economy would look like if certain companies were forced to cease production in various scenarios – all aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 20%.

“In the first scenario, we looked at what would happen if only CO2 emissions were taken into account,” explains Stefan Thurner from the CSH. In order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20%, the country’s seven largest emitters would have to cease operations. “In the meantime, however, around 29% of jobs and 32% of the country’s economic output would be lost. The idea is completely unrealistic; no politician would ever attempt such a thing,” says Thurner.

Furthermore, when greenhouse gas emissions and the size of the companies are considered, serious economic consequences result.

A two-factor approach

“Two factors are crucial – the CO2 emissions of a company, as well as what systemic risks are associated with it, i.e. what role the company plays in the supply network,” explains Stangl. CSH researchers developed the Economic Systemic Risk Index (ESRI) in an earlier study. It estimates the economic loss that would result if a company ceased production.

Taking these two factors into account — a company’s greenhouse gas emissions and its risk index for the country’s economy – the researchers calculated a new ranking of companies with large emissions relative to their economic impact.

According to the new ranking, a 20% reduction in CO2 emissions would require the top 23 companies on the list to cease operations. This, however, would only result in a loss of 2% of jobs and 2% of economic output.

At the company level

“In reality, companies would naturally try to find new suppliers and customers. We want to take this aspect into account in a further developed version of our model in order to obtain an even more comprehensive picture of the green transformation. However, our study clearly shows that we need to take the supply network at the company level into account if we want to evaluate what a particular climate policy will achieve,” say the authors of the study. This is the only way to assess which companies will be affected by a particular measure and how this will affect their trading partners, according to them.

The availability of company-level data has been largely lacking in Austria. The risk assessment is normally done at the sector level, for example, how severely a measure affects the entire automotive or tourism industry.

“This puts us at a disadvantage compared to other countries such as Hungary, Spain or Belgium, where detailed data is available at company level. In these countries, VAT is not recorded cumulatively, but in a standardized way for all business-to-business transactions, which means that extensive information is available on the country’s supply network,” explains Thurner.

____________________________________________________________________________________

About CSH

The Complexity Science Hub (CSH) is Europe’s research center for the study of complex systems. We derive meaning from data from a range of disciplines – economics, medicine, ecology, and the social sciences – as a basis for actionable solutions for a better world. Established in 2015, we have grown to over 70 researchers, driven by the increasing demand to gain a genuine understanding of the networks that underlie society, from healthcare to supply chains. Through our complexity science approaches linking physics, mathematics, and computational modeling with data and network science, we develop the capacity to address today’s and future challenges.

Journal

Nature Sustainability

DOI

10.1038/s41893-024-01321-x

Method of Research

Computational simulation/modeling

Subject of Research

People

Article Title

Firm-level supply chains to minimize decarbonization unemployment and economic losses

Article Publication Date

15-Apr-2024

COI Statement

The authors declare no competing interests.