Credit: Lauren Aleza Kaye / ETH Zurich

Scientists have been researching luminous coloured quantum dots (QDs) since the 1980s. These nanocrystals are now part of our everyday lives: the electronics industry uses them in LCD televisions to enhance colour reproduction and image quality.

Quantum dots are spherical nanocrystals made of a semiconductor material. When these crystals are excited by light, they glow green or red – depending on their size, which is typically between 2 and 10 nanometres. The spherical forms can be produced in a highly controlled manner.

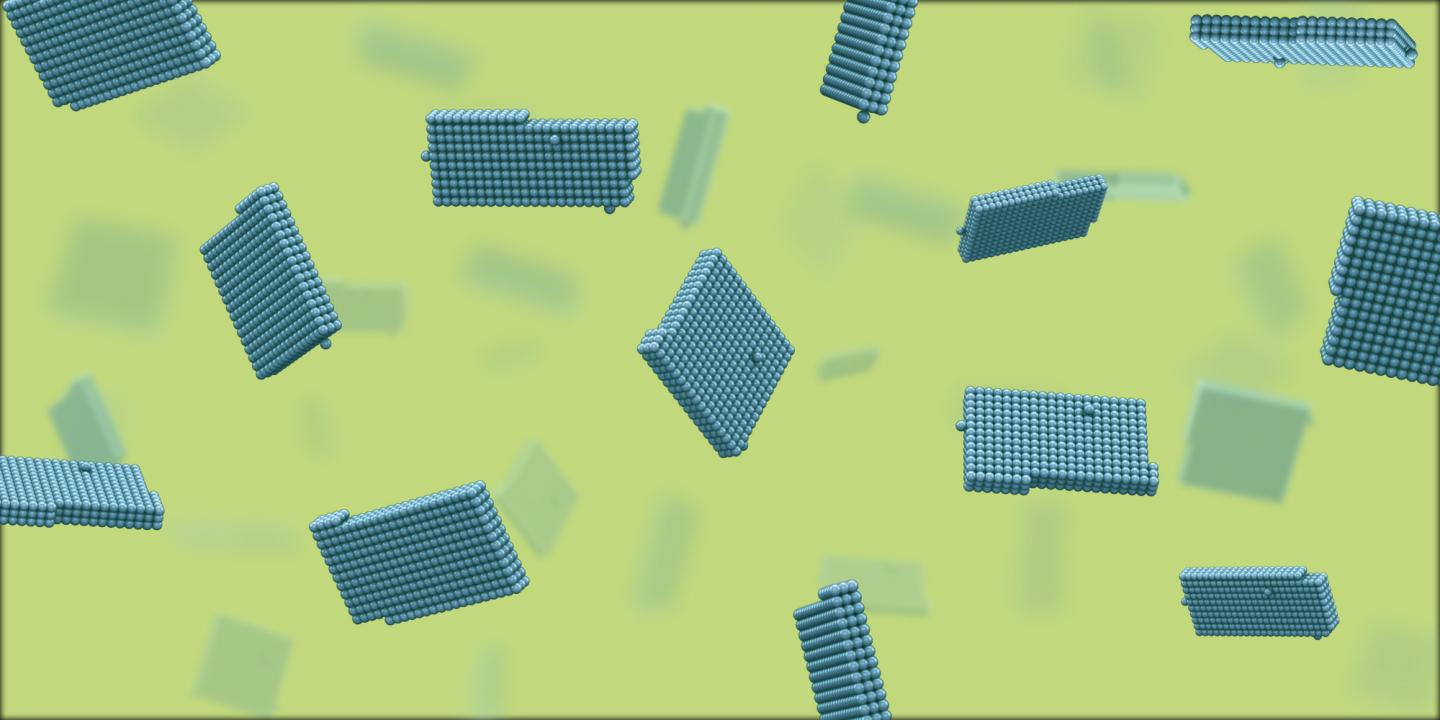

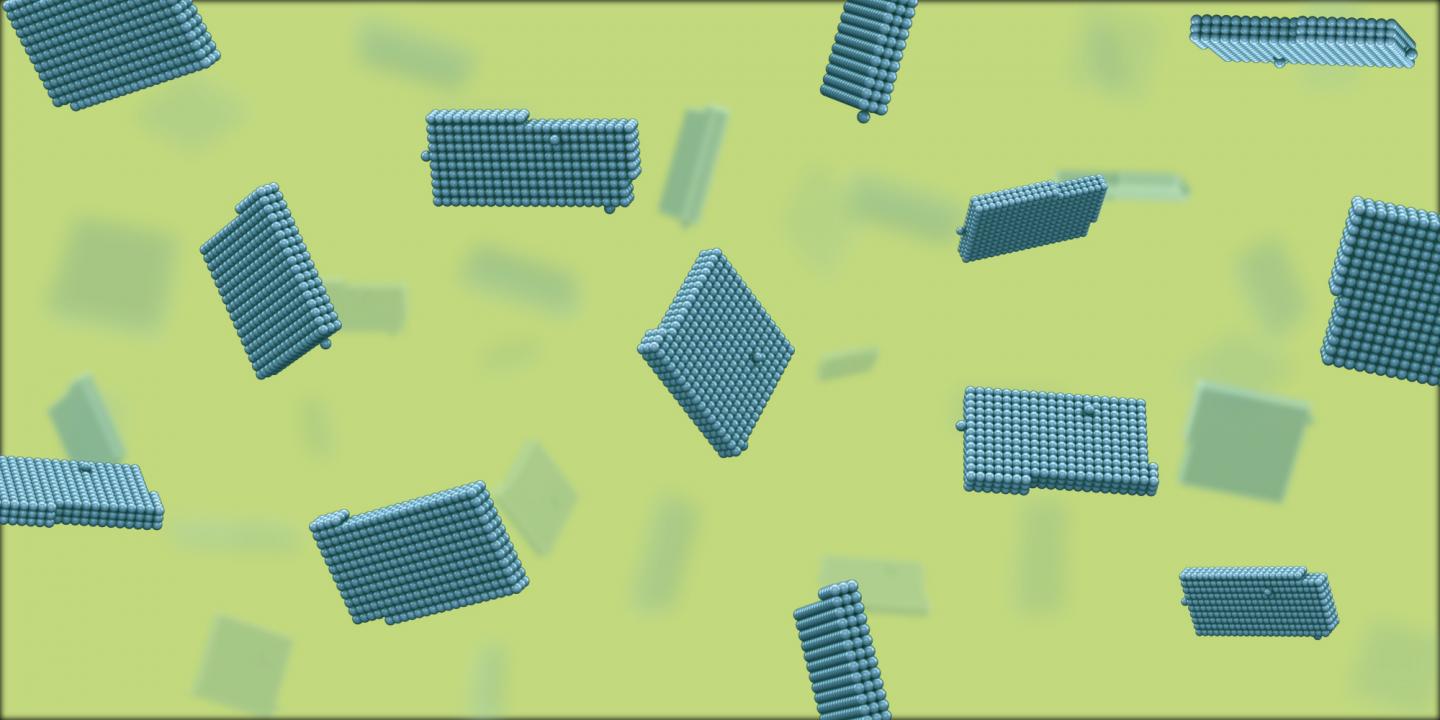

Rectangular ultra-thin crystals

A few years ago, a new type of nanocrystal caught the attention of researchers more or less by chance: nanoplatelets. Like quantum dots, these two-dimensional structures are just a few nanometres in size, but have a more uniform flat, rectangular shape. They are extremely thin, often just the width of a few atomic layers, giving the platelets one of their most striking properties – their extremely pure colour.

Until now the mechanism that explains how such platelets form has been a mystery. In collaboration with a US-based researcher, ETH professor David Norris and his team have now solved this mystery: "We now know that there's no magic involved in producing nanoplatelets, just science" stressed the Professor of Materials Engineering.

In a study just published in the scientific journal Nature Materials, the researchers show how cadmium selenide nanoplatelets take on their particular flat shape.

Growth without a template

Researchers had previously assumed that this highly precise form required a type of template. Scientists suspected that a mixture of special compounds and solvents produced a template in which these flat nanocrystals then formed.

However, Norris and his colleagues found no evidence that such shape templates had any role. On the contrary, they found that the platelets can grow through the simple melting of the raw substances cadmium carboxylate and selenium, without any solvent whatsoever.

Theoretical growth model devised

The team then took this knowledge and developed a theoretical model to simulate the growth of the platelets. Thanks to this model, the scientists show that a crystallised core occurs spontaneously with just a few cadmium and selenium atoms. This crystallised nucleus can dissolve again and reconfigure in a different form. However, once it has exceeded a critical size, it grows to form a platelet.

For energy-related reasons, the flat crystal grows only on its narrow side, up to 1,000 times faster than on its flat side. Growth on the flat side is significantly slower because it would involve more poorly bonded atoms on the surface, requiring energy to stabilise them.

Model verified experimentally

Ultimately, the researchers also succeeded in confirming their model experimentally by creating pyrite (FeS2) nanoplatelets in the lab. They produced the platelets exactly according to the model prediction using iron and sulphur ions as base substances.

"It's very interesting that we were able to produce these crystals for the first time with pyrite," says Norris. "That showed us that we can expand our research to other materials." Cadmium selenide is the most common semiconductor material used in the research of nanocrystals; however, it is highly toxic and thus unsuitable for everyday use. The researchers' goal is to produce nanoplatelets made from less toxic or non-toxic substances.

Giving further development the green light

At present, Norris can only speculate about the future potential of nanoplatelets. He says that they may be an interesting alternative to quantum dots as they offer several advantages; for example, they can generate colours such as green better and more brightly. They also transmit energy more efficiently, which makes them ideal for use in solar cells, and they would also be suitable for lasers.

However, they have several disadvantages as well. Quantum dots, for example, allow infinitely variable colour through the formation of varying size crystals. Not so in the case of platelets: due to the stratification of the atomic layers, the colour can be changed only incrementally. Fortunately, this limitation can be mitigated with certain "tricks": by encapsulation of the platelets in another semiconductor, the wavelength of the light emitted can be tuned more precisely.

Only time will tell whether this discovery will attract the interest of the display industry. Some companies currently use organic LED (OLED) technology, while others use quantum dots. How the technology will evolve is unclear. However, the ability to investigate a broad variety of nanoplatelet materials due to this work may provide the semiconductor nanocrystal approach with a new edge.

###

Reference

Riedinger A, Ott FD, Mule A, Mazzotti S, Knüsel PN, Kress SJP, Prins F, Erwin SC, Norris DJ. An intrinsic growth instability in isotropic materials leads to quasi-two-dimensional nanoplatelets. Nature Materials, Published Online 3rd April 2017. DOI 10.1038/nmat4889

Media Contact

Prof. Dr. David Norris

[email protected]

41-446-325-360

@ETH_en

http://www.ethz.ch/index_EN

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag