A research team from New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYITCOM), led by Biomedical Sciences Instructor Satoru Kobayashi, Ph.D., has secured a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The three-year $428,400 grant will support innovative research that may deliver life-saving treatments for diabetic heart failure.

Credit: Satoru Kobayashi

A research team from New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine (NYITCOM), led by Biomedical Sciences Instructor Satoru Kobayashi, Ph.D., has secured a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The three-year $428,400 grant will support innovative research that may deliver life-saving treatments for diabetic heart failure.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 34 million Americans have diabetes, a condition that doubles their risk for heart disease. One form of heart disease, diabetic heart failure, occurs when excess blood sugar damages cardiovascular tissue, including the heart’s muscles. As damage accrues over time, the heart slowly loses its ability to pump blood to the body, leading to death.

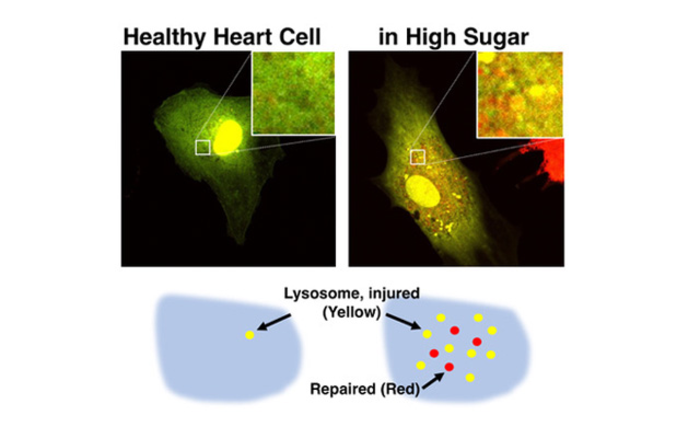

However, it is unclear how diabetic heart failure develops, given that the heart’s cells, like all cells in the body, contain built-in defense systems. Specifically, cells are armed with lysosomes, structures that repair damage and remove waste. In addition, pinpointing why cell defense systems fail is challenging, as many fluorescent dyes that make lysosomes visible under a microscope highlight either functional or impaired lysosomes, not both, and their staining effects are short-lived.

Kobayashi theorizes that diabetic heart failure develops when excess blood sugar lowers the acidity of lysosomes within heart muscle cells, rendering the cells defenseless. The researchers have also developed a fluorescent microscopy imaging technique that will stain lysosomes long enough to trace how they are impaired, as well as how their defensive properties can be restored.

“Lysosomes are very acidic, which allows them to digest and remove harmful cell waste, but excess blood sugar may lower their acidity, impairing the cell’s defense system. Even worse, the injured lysosomes leak acids and undigested wastes, which accelerates cellular damage. This may explain why the diabetic heart cannot heal itself,” says Kobayashi, who has dedicated his career to researching new treatments for heart disease.

Using their innovative imaging technique, the researchers will analyze how changes in lysosome acidity impact heart function in mice with developing diabetes. The study’s subjects will be split into two groups: those with hearts containing more impaired lysosomes (lowered acidity) vs. those with hearts containing lysosomes that are better protected (reinforced acidity). If protecting lysosomes improves heart function, the findings may lead to new treatments for heart failure.

Other NYITCOM researchers involved include Biomedical Sciences Professor and Department Chair Anthony (Martin) Gerdes, Ph.D., Senior Research Associate Yuan Huang, Ph.D., and Associate Professor Youhua Zhang, Ph.D.

The NIH, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, is the largest biomedical research agency in the world. This grant was supported by the NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under Award Number 1R15HL161737-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.