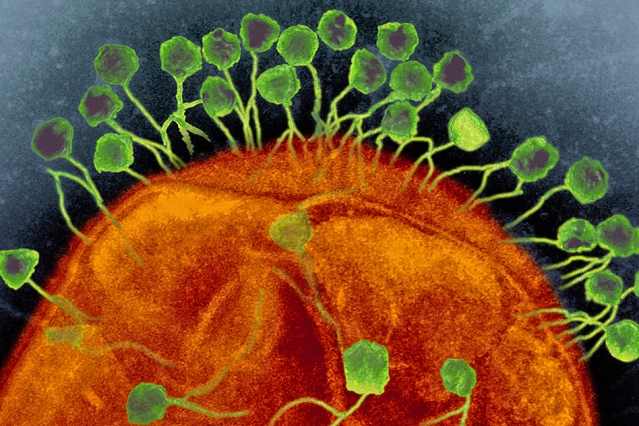

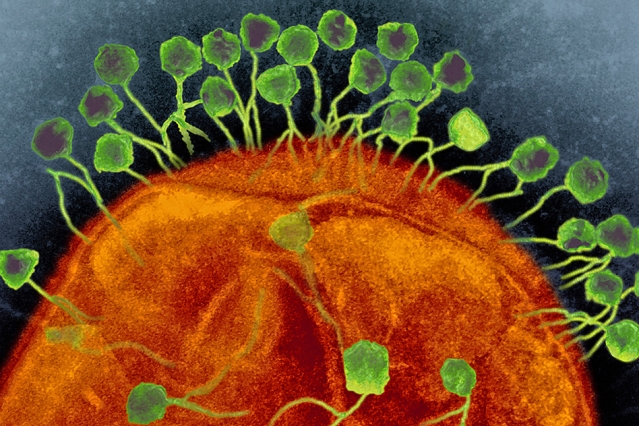

CRISPR systems are found in many different bacterial species, and have evolved to protect host cells against infection by viruses.

Image courtesy of Broad Institute/Science Photo Images

A team including the scientist who first harnessed the CRISPR-Cas9 system for mammalian genome editing has now identified a different CRISPR system with the potential for even simpler and more precise genome engineering.

In a study published today in Cell, Feng Zhang and his colleagues at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, with co-authors Eugene Koonin at the National Institutes of Health, Aviv Regev of the Broad Institute and the MIT Department of Biology, and John van der Oost at Wageningen University, describe the unexpected biological features of this new system and demonstrate that it can be engineered to edit the genomes of human cells.

“This has dramatic potential to advance genetic engineering,” says Eric Lander, director of the Broad Institute. “The paper not only reveals the function of a previously uncharacterized CRISPR system, but also shows that Cpf1 can be harnessed for human genome editing and has remarkable and powerful features. The Cpf1 system represents a new generation of genome editing technology.”

CRISPR sequences were first described in 1987, and their natural biological function was initially described in 2010 and 2011. The application of the CRISPR-Cas9 system for mammalian genome editing was first reported in 2013, by Zhang and separately by George Church at Harvard University.

In the new study, Zhang and his collaborators searched through hundreds of CRISPR systems in different types of bacteria, searching for enzymes with useful properties that could be engineered for use in human cells. Two promising candidates were the Cpf1 enzymes from bacterial species Acidaminococcus and Lachnospiraceae, which Zhang and his colleagues then showed can target genomic loci in human cells.

“We were thrilled to discover completely different CRISPR enzymes that can be harnessed for advancing research and human health,” says Zhang, the W.M. Keck Assistant Professor in Biomedical Engineering in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

The newly described Cpf1 system differs in several important ways from the previously described Cas9, with significant implications for research and therapeutics, as well as for business and intellectual property:

- First: In its natural form, the DNA-cutting enzyme Cas9 forms a complex with two small RNAs, both of which are required for the cutting activity. The Cpf1 system is simpler in that it requires only a single RNA. The Cpf1 enzyme is also smaller than the standard SpCas9, making it easier to deliver into cells and tissues.

- Second, and perhaps most significantly: Cpf1 cuts DNA in a different manner than Cas9. When the Cas9 complex cuts DNA, it cuts both strands at the same place, leaving “blunt ends” that often undergo mutations as they are rejoined. With the Cpf1 complex the cuts in the two strands are offset, leaving short overhangs on the exposed ends. This is expected to help with precise insertion, allowing researchers to integrate a piece of DNA more efficiently and accurately.

- Third: Cpf1 cuts far away from the recognition site, meaning that even if the targeted gene becomes mutated at the cut site, it can likely still be recut, allowing multiple opportunities for correct editing to occur.

- Fourth: The Cpf1 system provides new flexibility in choosing target sites. Like Cas9, the Cpf1 complex must first attach to a short sequence known as a PAM, and targets must be chosen that are adjacent to naturally occurring PAM sequences. The Cpf1 complex recognizes very different PAM sequences from those of Cas9. This could be an advantage in targeting some genomes, such as in the malaria parasite as well as in humans.

“The unexpected properties of Cpf1 and more precise editing open the door to all sorts of applications, including in cancer research,” says Levi Garraway, an institute member of the Broad Institute, and the inaugural director of the Joint Center for Cancer Precision Medicine at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the Broad Institute. Garraway was not involved in the research.

An open approach to empower research

Zhang, along with the Broad Institute and MIT, plan to share the Cpf1 system widely. As with earlier Cas9 tools, these groups will make this technology freely available for academic research via the Zhang lab’s page on the plasmid-sharing website Addgene, through which the Zhang lab has already shared Cas9 reagents more than 23,000 times with researchers worldwide to accelerate research. The Zhang lab also offers free online tools and resources for researchers through its website.

The Broad Institute and MIT plan to offer nonexclusive licenses to enable commercial tool and service providers to add this enzyme to their CRISPR pipeline and services, further ensuring availability of this new enzyme to empower research. These groups plan to offer licenses that best support rapid and safe development for appropriate and important therapeutic uses.

“We are committed to making the CRISPR-Cpf1 technology widely accessible,” Zhang says. “Our goal is to develop tools that can accelerate research and eventually lead to new therapeutic applications. We see much more to come, even beyond Cpf1 and Cas9, with other enzymes that may be repurposed for further genome editing advances.”

Story Source:

The above post is reprinted from materials provided by MIT NEWS