Credit: Shawn Rocco/Duke Health

DURHAM, N.C. — Though their purpose and function are still largely unknown, mirror neurons in the brain are believed by some neuroscientists to be central to how humans relate to each other. Deficiencies in mirror neurons might also play a role in autism and other disorders affecting social skills.

Scientists have previously shown that when one animal watches another performing a motor task, such as reaching for food, mirror neurons in the motor cortex of the observer's brain start firing as though the observer were also reaching for food.

New Duke research appearing March 29 in the journal Scientific Reports suggests mirroring in monkeys is also influenced by social factors, such as proximity to other animals, social hierarchy and competition for food.

The Duke team found that when pairs of monkeys interacted during a social task, the brains of both animals showed episodes of high synchronization, in which pools of neurons in each animal's motor cortex tended to fire at the same time. This phenomenon is known as interbrain cortical synchronization.

"We believe our study has the potential to open a complete new field of investigation in modern neuroscience by demonstrating that even the simplest functions of the motor cortex, such as creating body movements, are heavily influenced by the type of social relationships among the animals participating," said senior author Miguel Nicolelis, M.D., Ph.D.

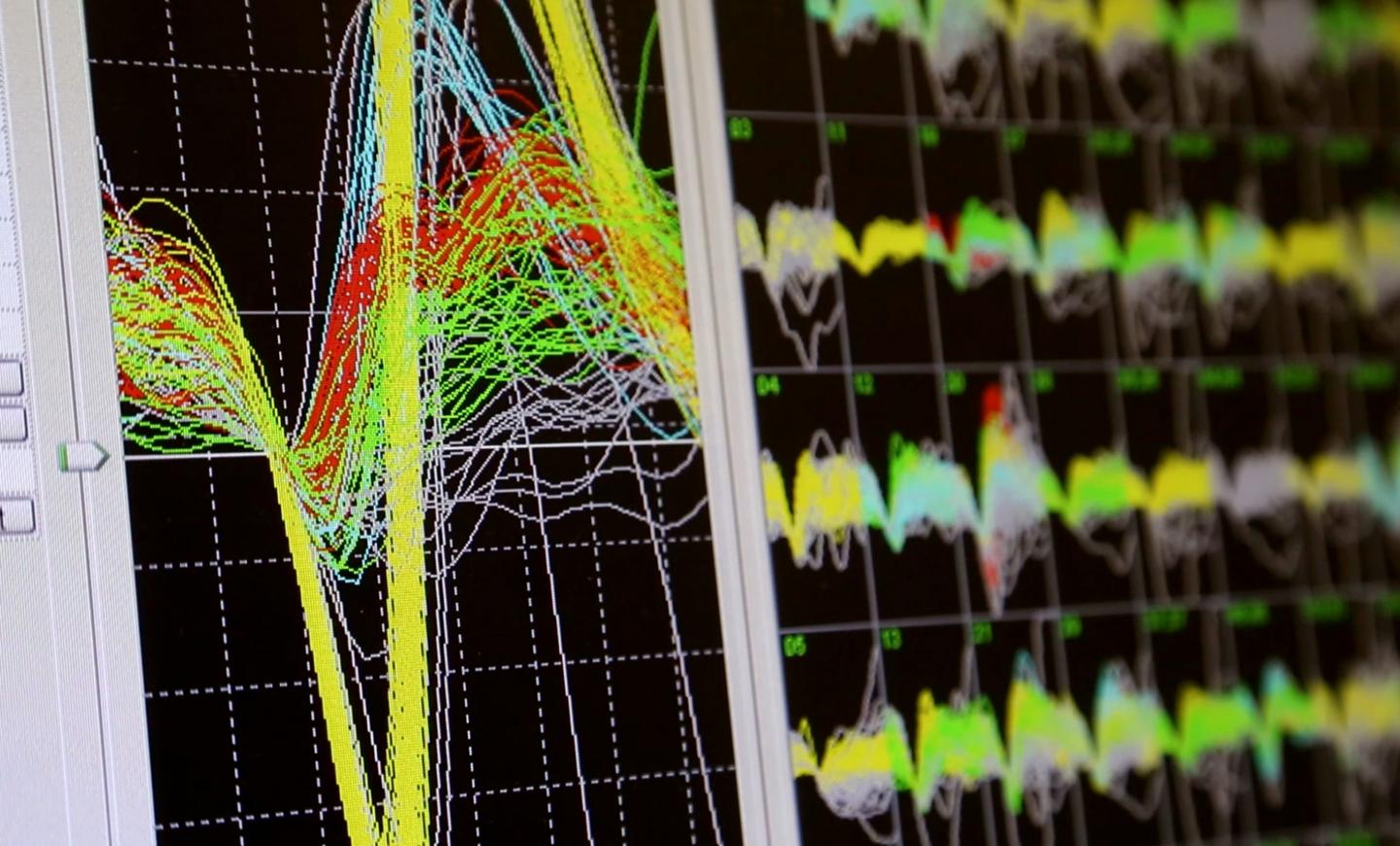

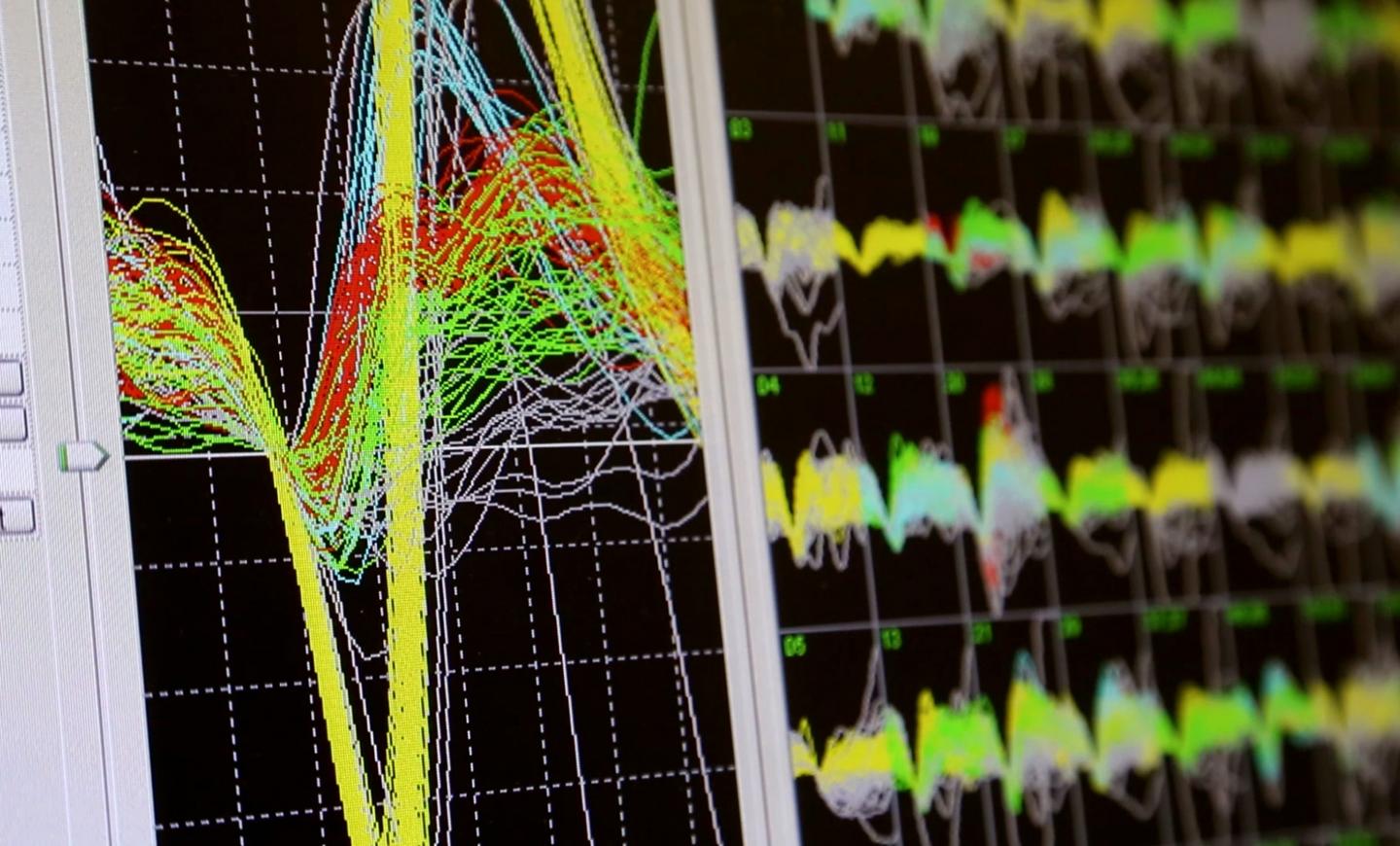

Previously, neuroscientists had limited their studies to recording brain activity in one animal at a time. What makes this research unique, Nicolelis said, is that the Duke team created a multi-channel wireless system to record the electrical activity of hundreds of neurons in the motor cortices of two monkeys simultaneously as they interacted in the same space.

During one task, one monkey, called the passenger, sat in an electronic wheelchair programmed to reach a reward across the room, a fresh grape. A second monkey, the observer, was also in the room watching the first monkey's trajectory toward the reward. Electrical activity in the motor cortex of each monkey's brain was recorded simultaneously. An analysis showed that when the passenger traveled across the room under the attentive gaze of the observer, pools of neurons in their motor cortices showed episodes of synchronization.

The researchers found these episodes of interbrain cortical synchronization (ICS) could predict the location of the passenger's wheelchair in the room, as well its velocity. The brain activity could also predict how close the animals were to each other, as well as the passenger's proximity to the reward.

The most compelling finding, they said, was that ICS could predict another key social parameter — the rank of the monkeys in the colony.

During tasks when the colony's most dominant monkey was traveling toward the reward under the observation of a lower-ranking animal, the magnitude of ICS grew steadily as the passenger approached the observer. Synchronization peaked when the animals were about three feet apart — close enough that one might be able to stretch out an arm to groom the other, or attack.

But when a lower-ranking monkey was the passenger and the dominant monkey was observing, ICS did not increase as the monkeys got closer, suggesting social rank plays a role in brain synchronization.

The researchers believe episodes of ICS were generated by the simultaneous activation of mirror-neurons in both the passenger's and observer's brains. They propose similar correlations between brain synchrony and social interaction might take place during human social interactions, as well.

The findings could lead to new diagnostics or treatments for conditions where neuronal mirroring might not follow typical patterns, as has been suggested in autism, they said. Measuring ICS in humans could also reveal how well groups work together, and even what types of training improve their brain synchrony and teamwork.

"Using a non-invasive version of this approach, we may be able to quantify how well professional athletes, musicians or dancers are working together, or if an audience is engaged in what they're seeing, listening or imagining," Nicolelis said. "This could be valuable for any social task that requires the synchronization of many individuals to improve social cohesion."

Nicolelis plans to explore brain synchrony in people through future trials at Duke using functional MRI and electrode caps.

###

In addition to Nicolelis, study authors included Po-He Tseng, Sankaranarayani Rajangam, Gary Lehew, and Mikhail A. Lebedev.

The research was supported by The Hartwell Foundation, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS073952) and the National Institute of Mental Health (DP1MH099903), both part of the National Institutes of Health.

Media Contact

Samiha Khanna

[email protected]

919-419-5069

@DukeHealth

http://dukehealthnews.org

Related Journal Article

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22679-x