Rice University bioengineers are developing a simple, highly accurate test to detect signs of HIV and its progress in patients in resource-poor settings.

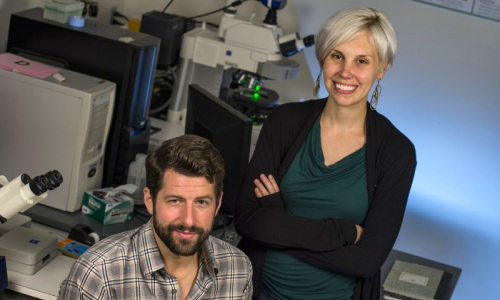

Rice graduate students Zachary Crannell, left, and Brittany Rohrman are leading Rice University bioengineers in an effort to develop an efficient test to detect signs of HIV and its progress in patients in low-resource settings. Photo Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

The current gold standard to diagnose HIV in infants and to monitor viral load depends on lab equipment and technical expertise generally available only in clinics, said Rice bioengineer Rebecca Richards-Kortum. The new research features a nucleic acid-based test that can be performed at the site of care.

Richards-Kortum, director of the Rice 360˚: Institute for Global Health Technologies, and her colleagues reported their results in the American Chemical Society journal Analytical Chemistry.

The proof-of-concept work by co-lead authors Zachary Crannell and Brittany Rohrman, both graduate students in the Richards-Kortum lab, follows their similar technique to detect the parasite that causes the diarrheal disease cryptosporidiosis, reported earlier this year.

The new technique would replace a complex lab procedure based on polymerase chain reaction with one that relies on recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA), a method to quickly amplify – that is, multiply – genetic markers found in blood to levels where they can be easily counted. In a test the team calls qRPA, a specific sequence in HIV DNA is targeted and tagged with fluorescent probes that can be seen and quantified by a portable machine. Software analysis of the fluorescing DNA allows clinicians to determine with great accuracy whether the virus is present in a patient’s blood and/or how much is there.

The researchers calibrated the test by also amplifying an internal positive control not found in human blood. “It’s amplified by the same primers as the HIV sequence, so it tells us that the assay is working properly,” Rohrman said.

The students originally intended their work to look for HIV in infants, but the technique can also help to track viral loads in older patients. “It’s important for clinicians to be able to quantitatively monitor patients’ viral loads in order to ensure the disease is responding to therapy,” Crannell said.

To be clinically viable, a DNA-based test for HIV has to be able to quantify virus loads over four orders of magnitude, from very low to very high, the researchers said. They reported the Rice test easily meets that goal.

They are developing tools for low-resource settings where high-tech lab equipment is not available. Although they used a thermal cycler, the researchers are working on a technique that will keep the entire procedure between room and body temperatures so that it can be performed at the point of care in the developing world.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Rice University.