Mice severely disabled by a multiple sclerosis (MS) – like condition could walk less than two weeks following treatment with human stem cells. The finding, which uncovers new avenues for treating MS, will be published online on May 15, 2014, in the journal Stem Cell Reports.

When scientists transplanted human stem cells into MS mice, they predicted the cells would be rejected, much like rejection of an organ transplant.

Expecting no benefit to the mice, they were surprised when the experiment yielded spectacular results.

“My postdoctoral fellow Dr. Lu Chen came to me and said, ‘The mice are walking.’ I didn’t believe her,” said co-senior author, Tom Lane, Ph.D., a professor of pathology at the University of Utah, who began the work at University of California, Irvine.

Within just 10 to 14 days, the mice regained motor skills. Six months later, they still showed no signs of slowing down.

“This result opens up a whole new area of research for us,” said co-senior author Jeanne Loring, Ph.D., co-senior author and professor at The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

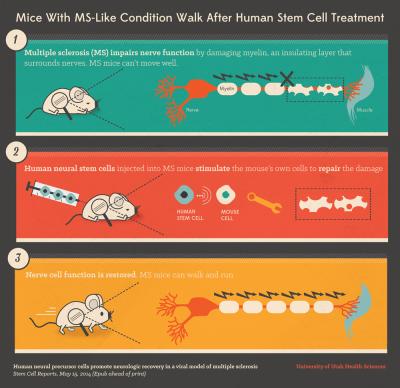

More than 2.3 million people worldwide have MS, a disease where the immune system attacks myelin, an insulation layer surrounding nerve fibers. The resulting damage inhibits nerve impulses, producing symptoms that include difficulty walking, impaired vision, fatigue and pain.

The MS mice treated with human stem cells experience a reversal of symptoms. Immune attacks are blunted, and damaged myelin is repaired, explaining their dramatic recovery. The discovery could help patients with latter, or progressive, stages of the disease, for whom there are no treatments.

Counterintuitively, the researchers’ original prediction that the mice would reject the stem cells, came true. There are no signs of the cells after one week. In that short window, they send chemical signals that instruct the mouse’s own cells to repair the damage caused by MS. This realization could be important for therapy development.

“Rather than having to engraft stem cells into a patient, which can be challenging, we might be able to put those chemical signals into a drug that can be used to deliver the therapy much more easily,” said Lane.

With clinical trials as the long-term goal, the next steps are to assess durability and safety of the stem cell therapy in mice.

“I would love to see something that could promote repair and ease the burden that patients with MS have,” said Lane.

“This result opens up a whole new area of research for us,” said co-senior author Jeanne Loring, Ph.D., co-senior author and professor at The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

More than 2.3 million people worldwide have MS, a disease where the immune system attacks myelin, an insulation layer surrounding nerve fibers. The resulting damage inhibits nerve impulses, producing symptoms that include difficulty walking, impaired vision, fatigue and pain.

The MS mice treated with human stem cells experience a reversal of symptoms. Immune attacks are blunted, and damaged myelin is repaired, explaining their dramatic recovery. The discovery could help patients with latter, or progressive, stages of the disease, for whom there are no treatments.

1) Multiple sclerosis (MS) impairs nerve function by damaging myelin, an insulating layer that surrounds nerves. MS mice can’t move well. 2) Human neural stem cells injected into MS mice stimulate the mouse’s own cells to repair the damage. 3) Nerve cell function is restored. MS mice can walk and run. Photo Credit: University of Utah Health Sciences Office of Public Affairs

Counterintuitively, the researchers’ original prediction that the mice would reject the stem cells, came true. There are no signs of the cells after one week. In that short window, they send chemical signals that instruct the mouse’s own cells to repair the damage caused by MS. This realization could be important for therapy development.

“Rather than having to engraft stem cells into a patient, which can be challenging, we might be able to put those chemical signals into a drug that can be used to deliver the therapy much more easily,” said Lane.

With clinical trials as the long-term goal, the next steps are to assess the durability and safety of the stem cell therapy in mice.

“I would love to see something that could promote repair and ease the burden that patients with MS have,” said Lane.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by University of Utah Health Sciences.