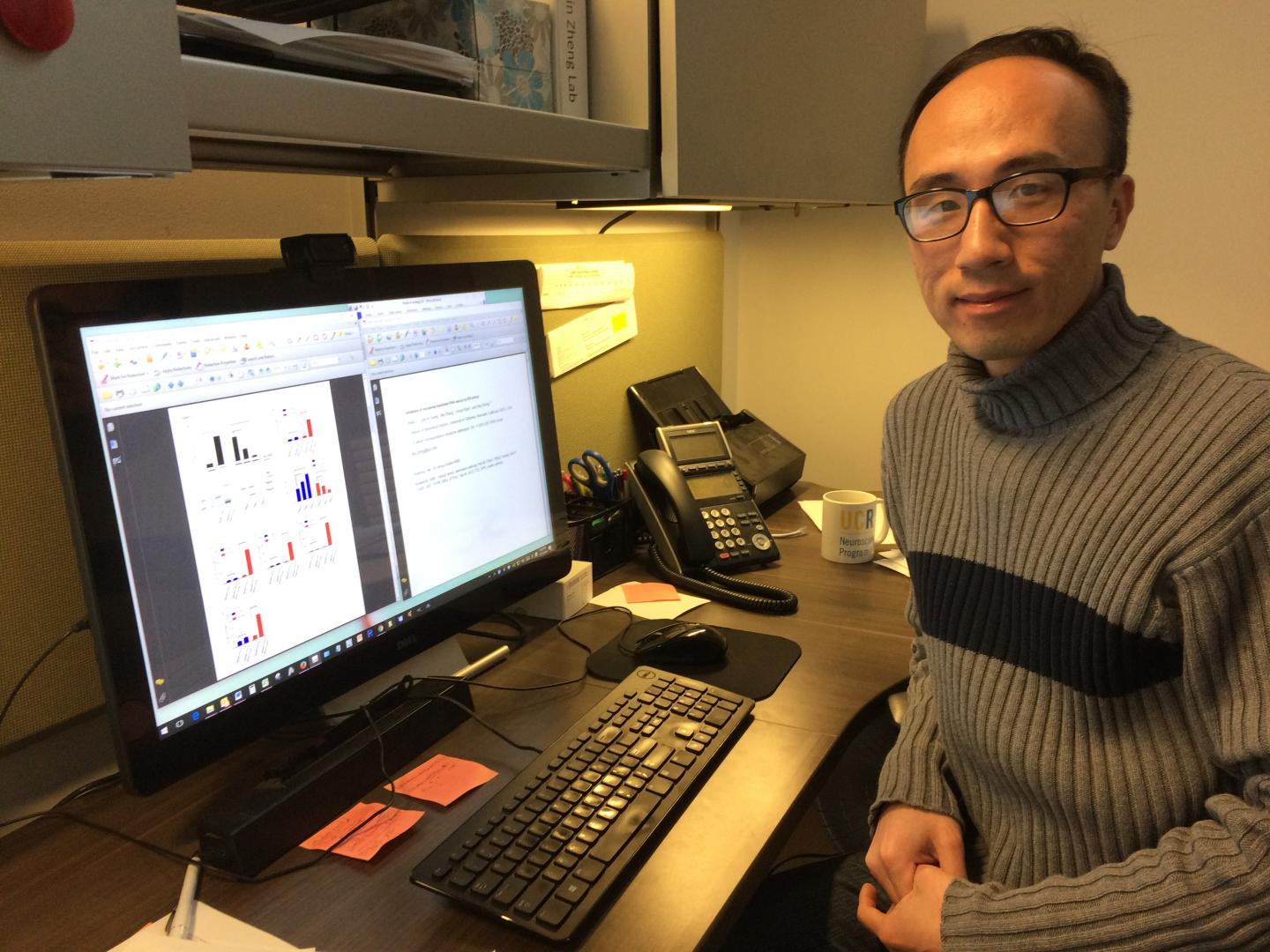

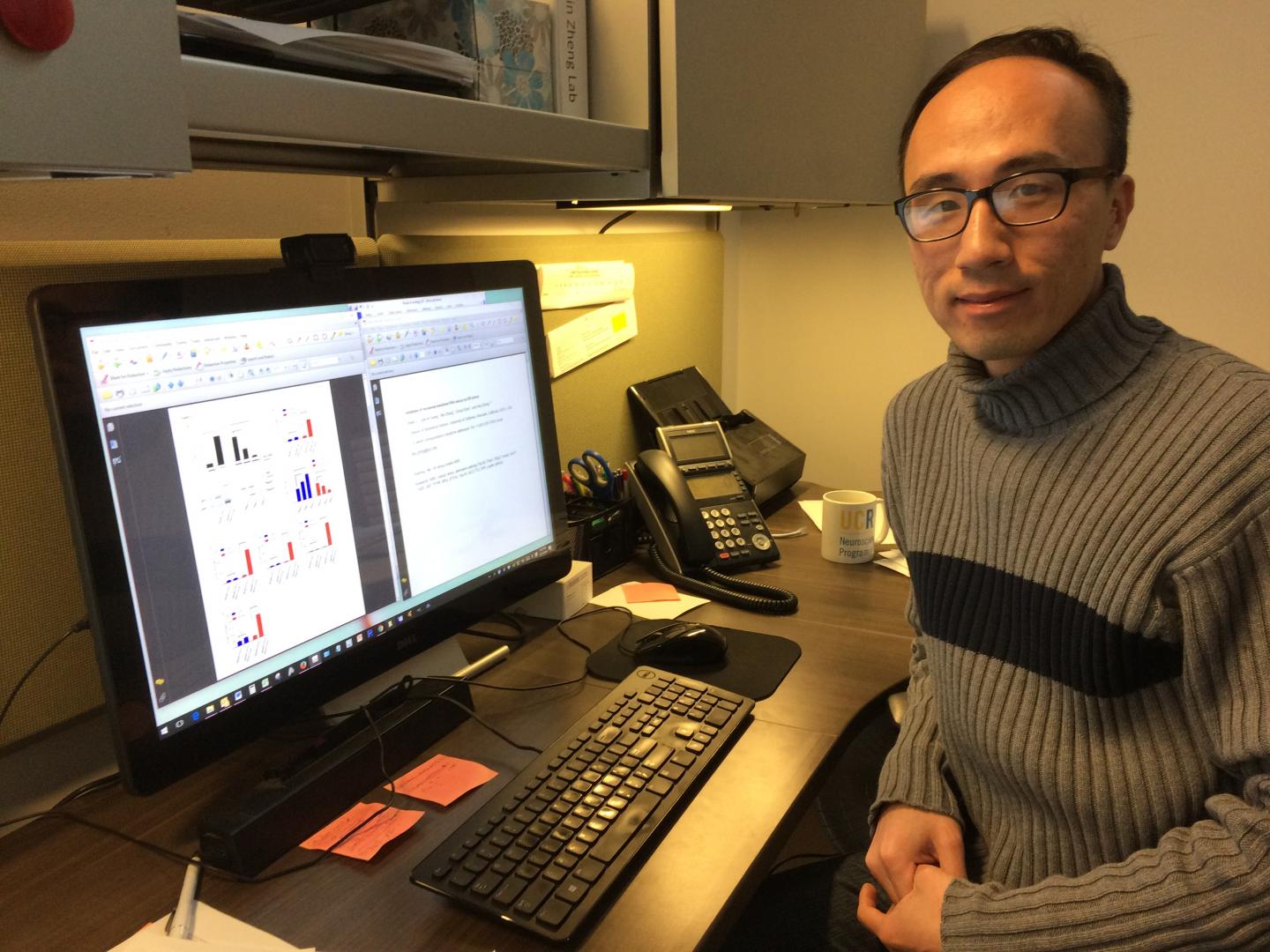

Credit: I. Pittalwala, UC Riverside.

RIVERSIDE, Calif. – In cells, DNA is first converted to RNA, and RNA is next converted to proteins–a complicated process involving several other steps. Nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD) is a processing pathway in cells that, like a broom, cleans up erroneous RNA to prevent its productive conversion into an aberrant protein, which could lead to disease.

In some diseases, like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, also called Lou Gehrig's disease), excessive junk RNA is produced, possibly contributing to the disease. In such instances, more NMD is useful to get rid of the junk RNA.

In other diseases, such as muscular dystrophy and cystic fibrosis, a decrease in NMD is a better option. In these diseases, the NMD pathway eliminates the RNA, resulting in a complete loss of the gene function. But a defective RNA may translate to a semi-functional protein, which is better than no RNA for protein formation in cells. And so, a tuned-down NMD is more useful.

Sika Zheng, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences in the School of Medicine at the University of California, Riverside, and colleagues now report in the journal RNA (volume 23, no.3, March 2017 issue) that they have come up with a method in the lab that detects NMD efficiency inside the cell.

"Our method can screen a host of chemicals and allows us to identify molecules that regulate this efficiency," Zheng said. "We have already identified thapsigargin as a molecule that indirectly and robustly inhibits NMD."

The new method works by harnessing some normal targets of NMD and turning them into "reporters" of NMD activity. The method relies on the knowledge that NMD is more than a quality-control mechanism; it can also determine the level of some naturally occurring RNA. The lower the abundance of these natural NMD in a cell, the stronger the NMD activity, and vice versa.

Zheng explained that in the past, measuring NMD efficiency was a cumbersome process and could be performed only on cell cultures, not directly on tissues.

"Our method is far easier and more sensitive, and for the first time can make measurements in all kinds of samples," Zheng said. "This is essential for drug screening. We are going to screen a larger library of chemicals to identify molecules that either boost or weaken NMD, which should help develop better and more targeted drugs for treating ALS, muscular dystrophy and cystic fibrosis."

###

Zheng was joined in the research by Zhelin Li (first author of the research paper), John K. Vuong, Min Zhang, and Cheryl Stork – all in the Division of Biomedical Sciences at UC Riverside.

The research was funded by a grant to Zheng from the National Institutes of Health.

The University of California, Riverside is a doctoral research university, a living laboratory for groundbreaking exploration of issues critical to Inland Southern California, the state and communities around the world. Reflecting California's diverse culture, UCR's enrollment is now nearly 23,000 students. The campus opened a medical school in 2013 and has reached the heart of the Coachella Valley by way of the UCR Palm Desert Center. The campus has an annual statewide economic impact of more than $1 billion. A broadcast studio with fiber cable to the AT&T Hollywood hub is available for live or taped interviews. UCR also has ISDN for radio interviews. To learn more, call (951) UCR-NEWS.

Media Contact

Iqbal Pittalwala

[email protected]

951-827-6050

@UCRiverside

http://www.ucr.edu

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag