Credit: Kwon lab

Generating mature and viable heart muscle cells from human or other animal stem cells has proven difficult for biologists. Now, Johns Hopkins researchers report success in creating them in the laboratory by implanting stem cells taken from a healthy adult or one with a type of heart disease into newborn rat hearts.

The researchers say the host animal hearts provide the biological signals and chemistry needed by the implanted immature heart muscle cells to progress and overcome the developmental blockade that traditionally stops their growth in lab culture dishes or flasks.

In a summary of the work published Jan. 10 in Cell Reports, the researchers say their method should help advance studies of how heart disease develops, along with the development of new diagnostic tools and treatments.

"Our concept of using a live animal host to enable maturation of cardiomyocytes can be expanded to other areas of stem cell research and really opens up a new avenue to getting stem cells to mature," says Chulan Kwon, Ph.D., associate professor of medicine and member of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine's Institute for Cell Engineering, who led the study.

According to Kwon, cell biologists have been historically unable to induce heart muscle cells to get past the point in development characteristic of newborns, even when they let them mature in dishes for a year.

Those neonatal heart cells, Kwon explains, are smaller and rounder than mature adult heart cells and generate very low pumping force. As a result, he adds, they aren't the best model for heart muscle diseases, nor do they accurately mimic the biology and chemistry of adult heart tissue.

Kwon's group recently showed that cells kept and grown in lab dishes weren't turning on the proper genes needed to let the cells transition to maturity, a phenomenon they attributed to the artificial conditions of growing cells in a dish. But they also found that those genes were similar to those activated, or turned on, in the hearts of newborn rats.

In their initial experiments designed to overcome the developmental roadblock, the researchers first created a cell line of immature heart cells taken from mouse embryonic stem cells. They next tagged these cells with a fluorescent protein and injected about 200,000 of the cells into the ventricle or lower heart chamber of newborn nude rats — rats with deficient immune systems that wouldn't attack and reject the newly introduced cells.

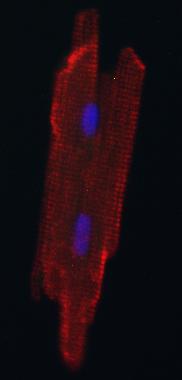

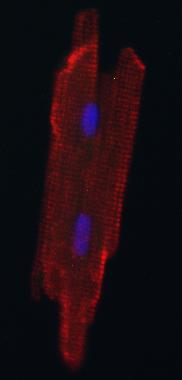

After about a week, Kwon reports, the fluorescent cells were still rounded and immature-looking. After a month, however, the cells looked like adult heart muscle cells — elongated with striped patterns.

When the researchers compared 312 genes in the individual mouse cells grown in the rat hearts to the genes found in both immature heart cells and adult heart muscle cells, they found the cells grown in the rat hearts had more in common with genetics of adult heart muscle cells.

The investigators confirmed that the new heart-grown cells could contract or beat like normal adult heart muscle cells using a type of optical microscopy.

In the next set of proof-of-concept experiments, Kwon's team worked with human adult skin cells from a healthy human donor that were chemically converted back into a stem cell-like state — known as induced pluripotent stem cells. A month after these cells were implanted into newborn rat hearts, the healthy human donor cells appeared rod-shaped and mature.

In the final proof-of-concept experiment, the researchers used induced pluripotent stem cells taken from a patient with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), an inherited form of heart disease and a leading cause of sudden death in young adults. These cells were of special interest because the genetic mutation that causes AVRC leads to symptoms only after the heart cells mature.

After a month growing the human ARVC immature heart cells in the rat heart ventricles, the cells began to demonstrate properties of heart tissue from patients with the disease, Kwon says. Specifically, they accumulated lots of fat and had more cells dying than healthy cells appearing.

This last experiment, Kwon says, proves that researchers can now consistently grow mature cardiomyocytes from patients with specific heart diseases to better study these diseases and identify treatments.

Kwon cautions that clinical use of these lab-grown cells is years away. But, he says, "The hope is that our work advances precision medicine by giving us the ability to make adult cardiomyocytes from any patient's own stem cells." Having that capability, he says, means having a way to test each patient for old and new drug sensitivities and value, and to have a scalable process to create large cell sources for heart regeneration."

###

Other authors that contributed to the study include Gun-Sik Cho, Dong Lee, Emmanouil Tampakakis, Peter Andersen, Hideki Uosaki, Stephen Chelko, Khalid Chakir, Ingie Hong, Kinya Seo, Gordon Tomaselli, Brian O'Rourke, Daniel Judge and David Kass of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Huei-Sheng Vincent Chen of Sanford-Burnham Medical Discovery Institute; Xiongwen Chen and Steven Houser of Temple University; and Cristina Basso of the University of Padua.

The research was funded by the Magic That Matters Fund; the Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund (2015-MSCRFI-1622); grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-0119012, HL-107153, R01 HL111198); the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD086026); a TRANSAC Strategic Research Grant; and the Foundation Leducq.

Media Contact

Vanessa McMains

[email protected]

410-502-9410

@HopkinsMedicine

http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org