Recent fears of major declines among insects have sent researchers scrambling for data on how they are actually doing.

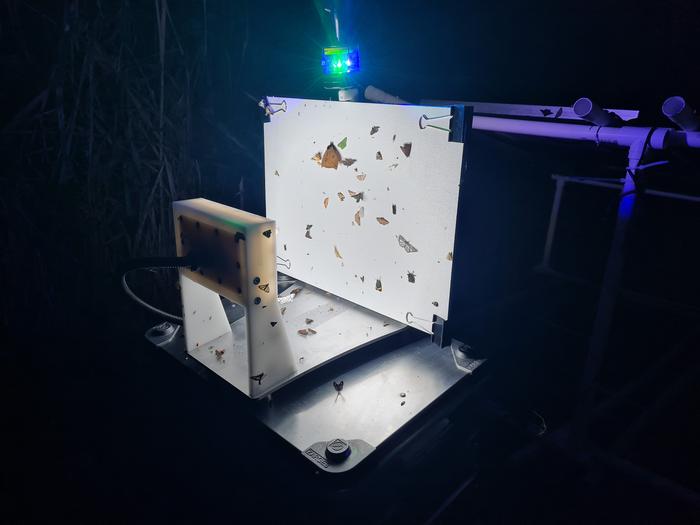

Credit: Jenna Lawson

Recent fears of major declines among insects have sent researchers scrambling for data on how they are actually doing.

“So far, such data are only available for a few insect groups and for selected regions. To improve on the status quo, we need urgent assessments of all types of insects in all parts of the world”, says Roel van Klink, senior researcher at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the lead editor of the special issue.

Given how numerous insects are, and how hard it is to tell them apart, obtaining complete information on insect trends has remained a tall order. Now technological breakthroughs are paving the way for global insect surveys.

Thanks to technological breakthroughs, we can now use all kinds of different properties of insects to track them. For instance, many insects make sounds, which are characteristic for their species. Using cheap devices spread across the environment, we may record these sounds and then assign them to the insects that produced them. As an alternative, we may attract insects to light then photograph them and identify the images. Using radar or even laser beams, we may sense insects remotely, and identify them based on their size and their wingbeats. Finally, we may extract DNA from insects – or from their traces in the environment, including water or air – and use the sequence of their genes to record and identify them.

“These novel methods have enormous potential to close the vast data gaps we have for insects. They can give us new, more and better data at lower costs in part due to the semi- or fully autonomous data collection. Novel technologies also typically avoids killing insects,” says Toke Thomas Høye, Professor of Ecology at the Department of Ecoscience, Aarhus University, Denmark.

Most importantly, the new methods reduce our dependence on experts, since the people who can tell insects apart are few and overburdened with work. Rather than using their valuable expertise on each individual sample of insects, they can teach computers to do the routine work – then themselves focus on the tasks for which their expertise is truly needed.

What adds to the need for automated processing of insect species is the fact that for most insects, there is no one who knows them. An estimated four out of five insect species are still unknown to science, and thus even lack names. To characterise them all will take over a thousand years if we continue by traditional methods.

“Now, computer-based methods and artificial intelligence can massively speed up the task of describing life on Earth. By teaching computers how to separate insects, we can make sense of billions of images, millions of sound recordings and trillions of DNA sequences” says Tomas Roslin, Professor of Insect Ecology at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU).

“Together, these technical advances will revolutionise our knowledge about insects. They make surveys of all types of insects feasible. While they have so far been developed in isolation from each other, our special issue is the start of their integration. By combining them, we will gain unprecedented insights into insects across the world.” says Dr Silke Bauer from the Swiss Federal Research Institute (WSL). “However, to allow global insights and equality, we need to make sure that both the technologies themselves and the data generated become accessible to everyone.”

These advances and principles are showcased in a new issue of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B [link to issue] – offering a comprehensive entry port for anyone interested in the insect world and how we may study it.

Journal

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences

DOI

10.1098/rstb.2023.0101

Method of Research

Literature review

Subject of Research

Animals

Article Title

Towards a toolkit for global insect biodiversity monitoring

Article Publication Date

6-May-2024

COI Statement

This theme issue was put together by the Guest Editor team under supervision from the journal’s Editorial staff, following the Royal Society’s ethical codes and best-practice guidelines. The Guest Editor team invited contributions and handled the review process. Individual Guest Editors were not involved in assessing papers where they had a personal, professional or financial conflict of interest with the authors or the research described. Independent reviewers assessed all papers. Invitation to contribute did not guarantee inclusion.