Since the mid-19th century, human activity has played a pivotal role in the rapid dissemination of Rice yellow mottle virus (RYMV) across the African continent, dramatically influencing the epidemiology and distribution of this agricultural pathogen. This revelation emerges from a comprehensive study led by Eugénie Hébrard at the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD) in France, published in the open-access journal PLOS Pathogens on June 17, 2025. By tracing the evolutionary and historical trajectories of RYMV, the research illuminates the intricate interplay between human history and plant disease spread, a dynamic previously underappreciated outside zoonotic viral contexts.

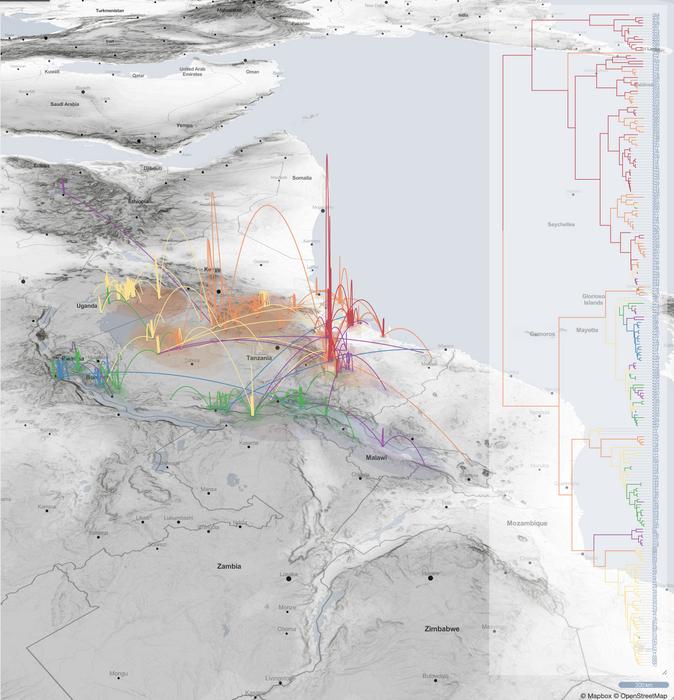

RYMV is a formidable viral pathogen that primarily infects rice and select related grass species, representing a significant threat to rice cultivation throughout the African continent. Unlike many viruses, RYMV is not seed-transmitted but is strongly associated with seeds, complicating containment strategies. The recent study harnessed extensive phylogeographic analyses to decipher the virus’s evolutionary pathways and spatial dispersion over more than a century. The researchers examined up to 335 viral samples collected over an expansive 770,000 square-mile area in East Africa, dating between 1966 and 2020. These samples underwent detailed genetic characterization focusing on viral protein-coding gene sequences and full-length genomes.

One of the study’s landmark findings is the identification of the Eastern Arc Mountains—now part of Tanzania—as the likely cradle of RYMV emergence around the mid-1800s. This biodiversity hotspot’s unique ecological conditions and human agricultural practices, particularly traditional slash-and-burn rice cultivation, appear to have fostered multiple spillover events wherein RYMV crossed over from wild grasses into cultivable rice fields. This zoonotic-like spillover phenomenon is notable for plant pathogens and underscores the virus’s capacity for adaptability and host range expansion. The virus’s early establishment in areas such as the Kilombero Valley and Morogoro region was tightly linked to these anthropogenically sculpted landscapes.

.adsslot_OyJA2j46Du{ width:728px !important; height:90px !important; }

@media (max-width:1199px) { .adsslot_OyJA2j46Du{ width:468px !important; height:60px !important; } }

@media (max-width:767px) { .adsslot_OyJA2j46Du{ width:320px !important; height:50px !important; } }

ADVERTISEMENT

The study further unveils that human-mediated transport profoundly affected RYMV dispersion across vast distances and ecosystems within Africa. Historical caravan routes that connected the Indian Ocean Coast to Lake Victoria served as conduits for virus movement in the late 1800s. Subsequently, in the waning years of the 19th century, the virus made an unprecedented leap from East Africa to West Africa, signifying long-range dissemination events facilitated by grain trade networks. The 20th century saw additional waves of expansion, with the virus migrating northward into Ethiopia during the latter half and eventually reaching Madagascar by the late 1970s. These patterns mirror historical trade and migration routes, accentuating the multifaceted modes of RYMV transmission.

Remarkably, the study also highlights an unexpected transmission pathway during the World War I period. Evidence suggests RYMV spread from the Kilombero Valley to the southern end of Lake Malawi, likely propelled by infected rice meant to sustain military personnel. This wartime seed movement illustrates how sociopolitical upheavals and conflicts mediated plant pathogen epidemiology, echoing similar dynamics observed in human and animal diseases during periods of war and displacement.

Central to these findings is the realization that contaminated rice seeds and plant material have served as key vectors in the virus’s propagation. The paradox here lies in RYMV not being seed-borne in a classical sense but nonetheless being extensively seed-associated. This distinction holds profound implications for management strategies: while the virus cannot be transmitted through the internal tissues of seeds, external contamination and seed handling practices have enabled cross-regional dissemination. Understanding the biological and agronomic underpinnings of this transmission mode is essential to formulating effective disease control measures.

From an evolutionary perspective, the genetic analyses in this research draw on both partial viral gene sequences coding for critical proteins and entire viral genomes, allowing for high-resolution temporal and spatial reconstructions. The phylogeographic approach elucidated multiple introductions and localized viral diversifications across East Africa. These genetic signatures underscore the virus’s ability to diversify concomitant with human agricultural expansions and changing trade dynamics across the continent, revealing a complex mosaic of lineage distributions influenced by anthropogenic factors.

This research shifts the paradigm by suggesting that plant viruses such as RYMV can spread with efficiency comparable to certain high-profile zoonotic viruses that infect humans. Previously, the discourse on viral mobility has largely centered on animal pathogens owing to their public health prominence. However, the demonstrated multimodal transmission of RYMV—incorporating biological, ecological, and sociohistorical dimensions—highlights the critical intersections between human geography, trade, warfare, and viral ecology in shaping plant pathogen dynamics.

Furthermore, the implications of this work extend beyond Africa’s borders. The demonstrated risk of intercontinental transmission of RYMV and similar plant viruses emphasizes the necessity for heightened biosecurity measures in global grain trade and seed exchange. The study serves as a prescient warning about the potential of plant viruses to breach continental boundaries through globalized agricultural networks, threatening food security in vulnerable regions worldwide.

The authors emphasize that this body of work is the culmination of a sustained, multidisciplinary, and international collaboration, integrating expertise in virology, phylogenetics, agronomy, and historical geography. It vividly illustrates how the confluence of modern molecular biology with detailed historical records can uncover the hidden narratives of crop diseases. Their insights pave the way for innovative disease surveillance and control approaches, rooted in an understanding of human-mediated ecological changes and their resultant biotic consequences.

In conclusion, this groundbreaking retrospective on RYMV underscores how human history—in its trade routes, warfare, and agricultural practices—has been inextricably linked to the emergence and spread of a devastating plant pathogen. Such integrative studies compel a reevaluation of plant disease management, incorporating sociohistorical context alongside biological factors. With global food challenges intensifying, these insights are vital for safeguarding staple crops like rice, particularly in regions where agriculture sustains millions.

Subject of Research: Not applicable

Article Title: Grains, trade and war in the multimodal transmission of Rice yellow mottle virus: An historical and phylogeographical retrospective

News Publication Date: 17-Jun-2025

References: Ndikumana I, Onaga G, Pinel-Galzi A, Rocu P, Hubert J, Wéré HK, et al. (2025) Grains, trade and war in the multimodal transmission of Rice yellow mottle virus: An historical and phylogeographical retrospective. PLoS Pathog 21(6): e1013168. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1013168

Image Credits: François Chevenet

Tags: agricultural pathogens in Africacontainment strategies for RYMVenvironmental factors in disease disseminationgenetic characterization of rice viruseshistorical epidemiology of rice diseaseshuman activity and plant diseaseimpact of trade on disease spreadinterplay between war and agriculturephylogeographic analysis of RYMVrice cultivation threats in AfricaRice yellow mottle virus spread in Africaviral evolution and agriculture