Using microscopically fine 3D printing technologies from TU Wien (Vienna) and sound waves used as tweezers at Stanford University (California), tiny networks of neurons have been created

Credit: Stanford University

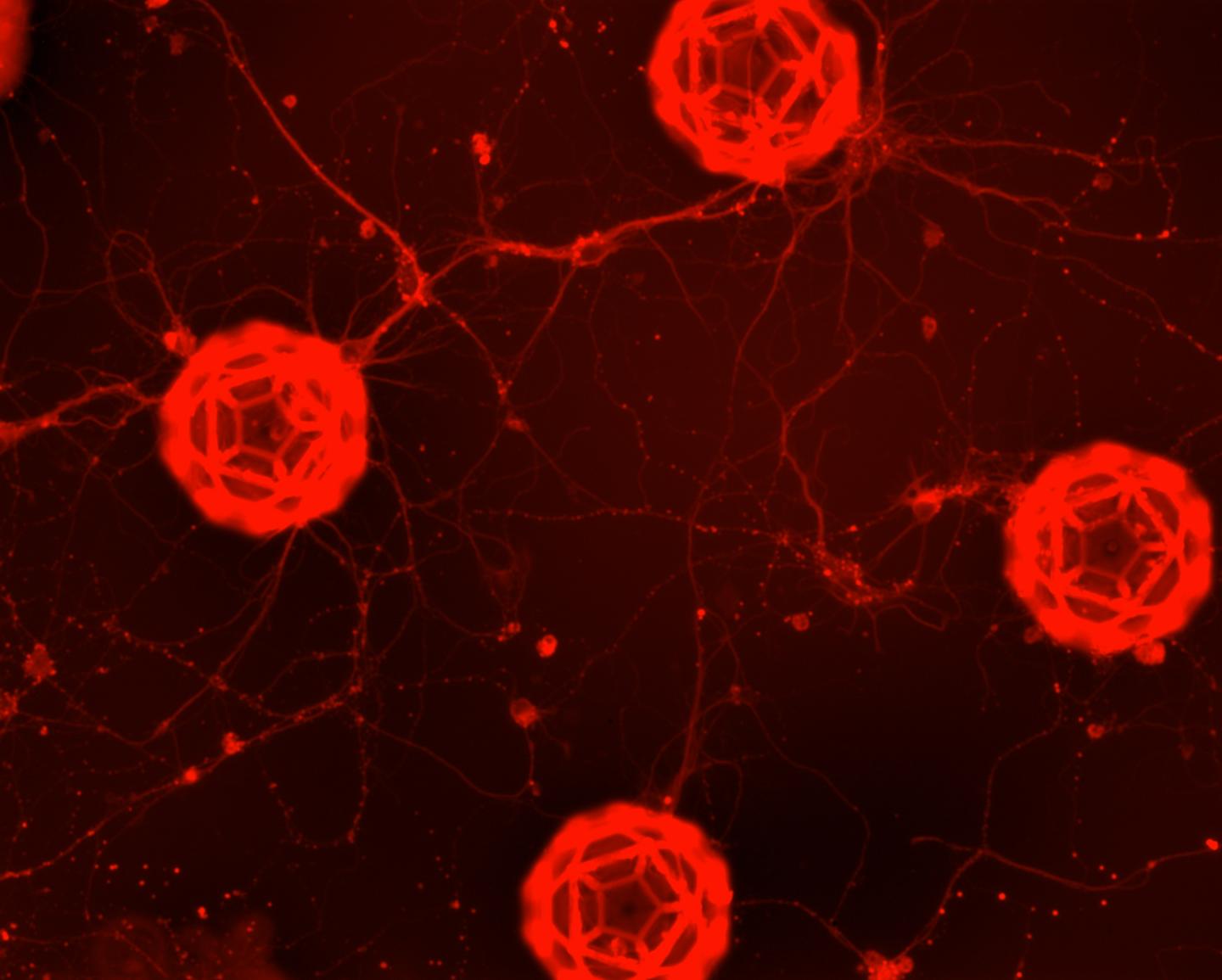

Microscopically small cages can be produced at TU Wien (Vienna). Their grid openings are only a few micrometers in size, making them ideal for holding cells and allowing living tissue to grow in a very specific shape. This new field of research is called “Biofabrication“.

In a collaboration with Stanford University, nerve cells have now been introduced into spherical cage structures using acoustic bioprinting technology, so that multicellular nerve tissue can develop there. It is even possible to create nerve connections between the different cages. To control the nerve cells, sound waves were used as acoustic tweezers.

Football Shaped Cages

“If you present living cells with a certain framework, you can strongly influence their behavior,” explains Prof. Aleksandr Ovsianikov, head of the 3D-Printing and Biofabrication research group at the Institute for Materials Science and Materials Technology at TU Wien. “3D printing enables the high-precision production of scaffolding structures, which can then be colonized with cells to study how living tissue grows and how it reacts”.

In order to grow large numbers of nerve cells in a small space, the research team decided to use so-called “buckyballs” – geometric shapes made of pentagons and hexagons that resemble a microscopic football.

“The openings of the buckyballs are large enough to allow cells to migrate into the cage, but when the cells coalesce, they can no longer leave the cage,” explains Dr. Wolfgang Steiger, who worked on high-precision 3D printing for biofabrication applications as part of his dissertation.

The tiny buckyball cages were manufactured using a process known as two-photon polymerization: a focused laser beam is used to start a chemical process at specific points in a liquid, which causes the material to harden at precisely these points. By steering the focal point of the laser beam through the liquid in a well-controlled way, three-dimensional objects can be produced with extremely high precision.

Acoustic Waves as Tweezers

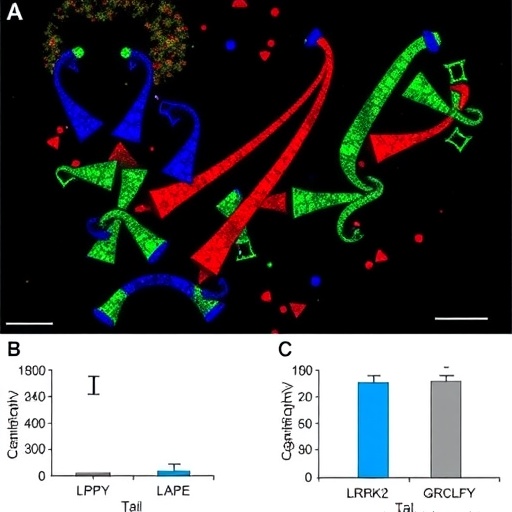

Not only creating the buckyballs, but also assembling cells into these balls through microscale openings is very challenging. An innovative 3-D acoustic bioprinting technology developed at the Stanford School of Medicine, successfully addressed this challenge. Prof. Utkan Demirci co-directs the Canary Center at Stanford for Early Cancer Detection and his research group, i.e., the Biosensing and Acoustic MEMS in Medicine (BAMM Lab) uses acoustic waves in biomedical applications from sensing cancer biomarkers to bioprinting 3-D tissue models to sensing.

“We generate acoustic oscillations in the solution in which the cells are located. The cells follow the sounds waves like rats follow the Pied Piper of Hamelin as in the legend In the process, nodes of oscillation form at certain points – similar to a vibrating string”, says Prof. Demirci. At these nodal points, the liquid is comparatively static. If cells are located at these points, they remain there; everywhere else they are moved away by the acoustic wave. The cells therefore move to the spots where they are not whirled around – and that is where the buckyballs were placed. The sound wave can thus be used in a very well-controlled way, almost like tweezers, to direct the cells to the desired location.

“The acoustic waves enabled us to fill the scaffold structures much more densely and efficiently than would have been possible with conventional methods of cell colonization,” reports Tanchen Ren, PhD, from Prof. Demirci’s research group.

Once the buckyballs had been successfully colonized with nerve cells in this way, they formed connections with neurons of neighboring buckyballs. “We see enormous potential here for using 3D printing to create and study neural networks in a targeted manner,” says Aleksandr Ovsianikov. “In this way, important biological questions can be investigated to which one would otherwise have no direct experimental access.”

###

Contact

Prof. Aleksandr Ovsianikov

Institute of Materials Science and Technology

TU Wien

Getreidemarkt 9, 1060 Wien

T +43-1-58801-30830

[email protected]

Prof. Utkan Demirci

Canary Center for Cancer Early Detection

Stanford University

Stanford, California

[email protected]

Media Contact

Florian Aigner

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.