For the past five years, a history professor has been working with a community in Guatemala to ensure that its water supply is safe. Recently, he received a national grant to continue this work.

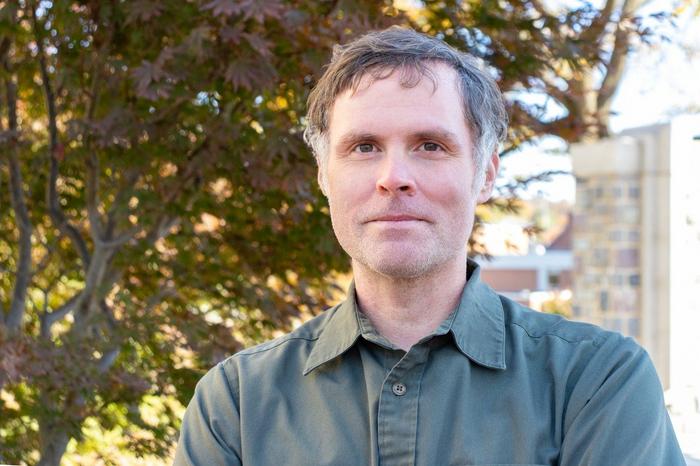

Credit: Photo by Leslie King for Virginia Tech.

For the past five years, a history professor has been working with a community in Guatemala to ensure that its water supply is safe. Recently, he received a national grant to continue this work.

The Science and Technology Studies program of the National Science Foundation awarded Nick Copeland, an anthropologist in Virginia Tech’s history department, a $360,000 grant for the project “Participatory Water Science and Resistance to Extractivism.”

Collaborations began in 2018, when Copeland met with community organizations that were concerned that the Escobal silver mine was polluting the regional water system. The team discovered elevated arsenic levels in surface waters near the mine and although team members could not determine that these were caused by the mine, they did find that that a water treatment plant was not removing arsenic from the water.

Since then, Copeland and his team, along with other organizations in Guatemala, have conducted workshops to teach grassroot water defenders — community members seeking to protect waterways — basic water science and how to use field testing kits. They also have continued to conduct testing with rural and Indigenous Guatemalan communities whose residents fear their sugar cane and oil palm plantations, among other extractive industries, are contaminating waterways.

The grant will allow the team to continue monitoring and water defender training for the next three years. The team also plans to ethnographically explore — through interviews and observations — ways that Indigenous environmental justice movements are using water science to address industrial development and how participation in science shapes the “knowledge, ethics, and skills” of community members, said Copeland.

Why it matters

The project explores the role community science — specifically environmental monitoring — plays in environmental justice movements. It also examines how different kinds of participation shape the outcomes of community science collaborations.

Copeland said that while rural and Indigenous populations are often extremely concerned about the negative impact that industrial projects have on their health and the environment, they don’t have evidence considered sufficient to demand accountability or force states to act. By validating and promoting community led science, the project aims to produce knowledge that will be useful for Indigenous water defenders.

While Copeland knows data alone won’t lead to policy changes, he believes it can galvanize grassroot resistance movements.

Goals of the project

- Equip community scientists with tools and skills to harness data about their waterways

- Conduct science that, because it threatens powerful interests, is deliberately left undone

- Create spaces of dialogue where professional science and local knowledge coexist on equal footing, and enrich one another, despite differences

- Assess the ability of community science, through interviews and observations, to influence corporate behavior, increase community control over water and land, and shape discussions over development

- Understand the limitations and risks of participatory science for Indigenous environmental justice movements

- Bolster efforts to create a center for collaborative research at Virginia Tech, aligning social sciences, humanities, and STEM the needs of marginalized communities

Who’s involved

- Nick Copeland, anthropologist and associate professor of history, principal investigator

- Kang Xia, plant and environmental sciences professor, co-principal investigator

- Korine Kolivras, geography professor, co-principal investigator

- Leigh Anne Krometis, biological systems engineering associate professor, co-principal investigator

Virginia Tech voice

“This project follows the lead of Indigenous communities and asks how we, as academics and scientists, can put our knowledge, technology, and skills to work for communities who are discriminated against and structurally excluded,” Copeland said. “Ultimately, there’s hardly a single megadevelopment project in the global south that’s not resisted by communities. Mining operations are set to expand to build batteries for electric cars. I support an energy transition, but I also recognize the right to hyper-privatized automobility is far less important than the right of rural communities to have water or to grow food. Those are tradeoffs many people rarely think about.”