Eating disorders are often misunderstood as lifestyle choices gone awry or oversimplified as the unfortunate result of societal pressures. These misconceptions obscure the fact that eating disorders are serious and potentially fatal mental illnesses that can be treated effectively with early intervention. Mortality rates for people with eating disorders are high compared to other mental illnesses, particularly for those with anorexia nervosa, a condition characterized by a severe restriction of food intake and an abnormally low body weight. People with anorexia can literally starve themselves, causing severe and potentially fatal medical complications. The second leading cause of death for people with anorexia is suicide.

Credit: ENIGMA Anorexia Working Group

Eating disorders are often misunderstood as lifestyle choices gone awry or oversimplified as the unfortunate result of societal pressures. These misconceptions obscure the fact that eating disorders are serious and potentially fatal mental illnesses that can be treated effectively with early intervention. Mortality rates for people with eating disorders are high compared to other mental illnesses, particularly for those with anorexia nervosa, a condition characterized by a severe restriction of food intake and an abnormally low body weight. People with anorexia can literally starve themselves, causing severe and potentially fatal medical complications. The second leading cause of death for people with anorexia is suicide.

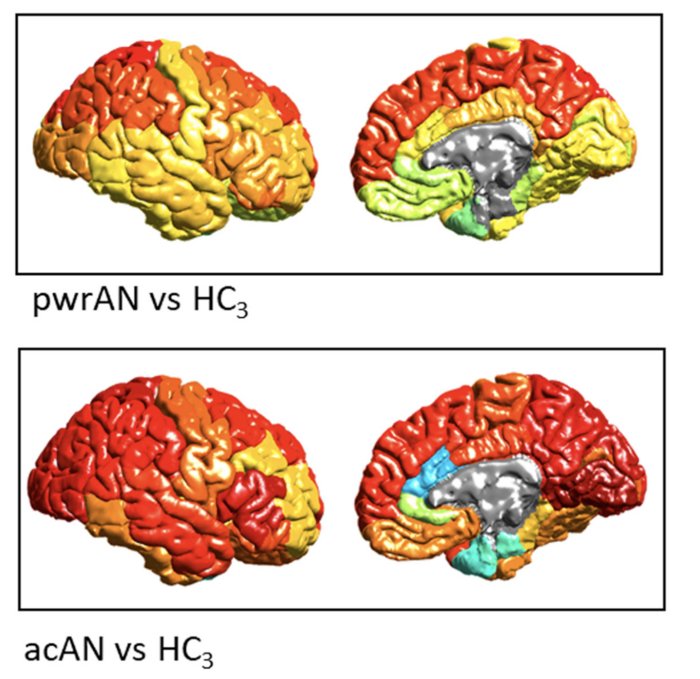

Now, a groundbreaking new study by a global team of researchers led by the Keck School of Medicine of USC’s Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute (Stevens INI) has revealed that individuals with anorexia demonstrate notable reductions in three critical measures of the brain: cortical thickness, subcortical volumes, and cortical surface area. These reductions are between two and four times larger than the abnormalities in brain size and shape of individuals with other mental illnesses. Reductions in brain size are particularly concerning, as they may imply the destruction of brain cells or the connections between them.

Equipped with these results, the research team is calling attention to the pressing need for prompt treatment to help people with anorexia avoid long-term, structural brain changes, which could lead to a variety of additional medical issues. Anorexia can be successfully treated with healthy weight gain and cognitive behavioral therapy. Ongoing work by the same group shows that successful treatment can have a positive impact on brain structure.

“By comparing nearly 2,000 pre-existing brain scans for people with anorexia, people in recovery and healthy controls, we found that for people in recovery from anorexia, reductions in brain structure were less severe,” says Paul M. Thompson, PhD, associate director of the Stevens INI. “This implies that early treatment and support can help the brain to repair itself.”

In addition to researchers from the Stevens INI, the research team includes neuroscientists from the Technical University in Dresden, Germany; the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York; University of Bath, UK; and King’s College London. The researchers came together under the ENIGMA Eating Disorders working group (ENIGMA-ED), a part of the ENIGMA Consortium, co-founded and led by Thompson. ENIGMA is an international effort to bring together researchers in imaging genomics, neurology, and psychiatry, to understand the link between brain structure, function and mental health.

Through advances in neuroimaging, researchers are gaining a better understanding of the link between serious mental health disorders and brain abnormalities. By demonstrating the effects of anorexia on brain structure, ENIGMA-ED has underscored the severity of the condition and the need for early intervention, while paving the way for the development of more effective treatments.

“The international scale of this work is extraordinary. Because scientists from twenty-two centers worldwide pooled their brain scans together, we were able to create the most detailed picture to date of how anorexia affects the brain, “says Thompson, professor of ophthalmology, neurology, psychiatry and the behavioral sciences, radiology, pediatrics and engineering. “The brain changes in anorexia were more severe than in any other psychiatric condition we have studied. Effects of treatments and interventions can now be evaluated, using these new brain maps as a reference.”

“This study exemplifies why the work at the Stevens INI is so essential,” says INI Director and longtime colleague of Thompson, Arthur W. Toga, PhD. “The goal of the ENIGMA Consortium is to bring researchers together from around the world so that we can combine existing data samples and really improve our power to examine the brain and detect the subtle brain alterations associated with a given illness. At the Stevens INI we apply this goal to all our large-scale studies. We are committed to participating in large studies with diverse research cohorts and sharing data to advance the entire scientific community.”

Access the full study ‘Brain Structure in Acutely Underweight and Partially Weight-Restored Individuals with Anorexia Nervosa – A Coordinated Analysis by the ENIGMA Eating Disorders Working Group’ published in Biological Psychiatry. Other USC co-authors contributing to the study include Neda Jahanshad, PhD, associate professor of neurology and biomedical engineering, and Sophia Thomopoulos, BS, consortium manager for the ENIGMA study.

Journal

Biological Psychiatry

DOI

10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.04.022

Method of Research

Meta-analysis

Subject of Research

People

Article Title

Brain Structure in Acutely Underweight and Partially Weight-Restored Individuals with Anorexia Nervosa – A Coordinated Analysis by the ENIGMA Eating Disorders Working Group

Article Publication Date

31-May-2022