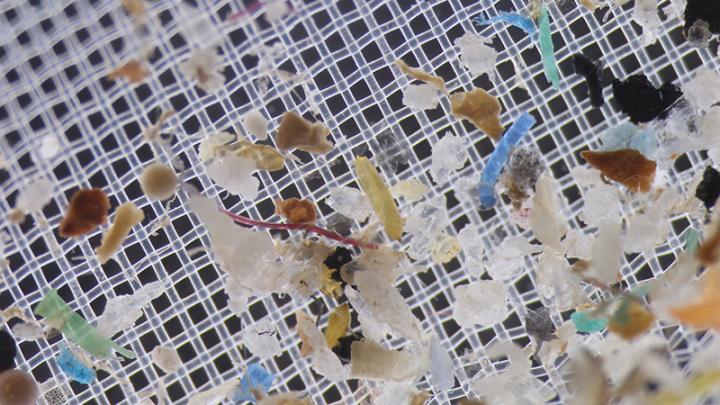

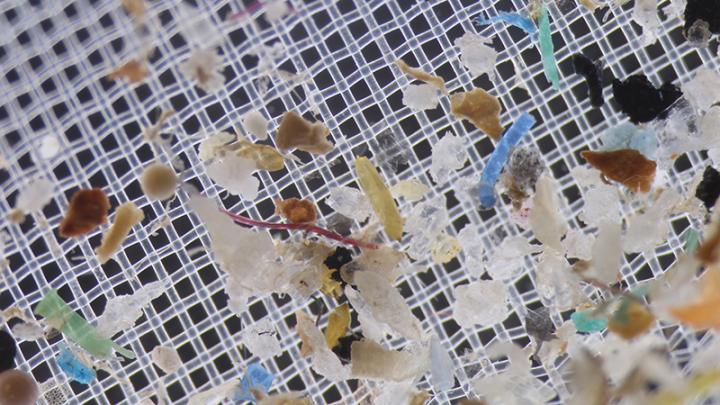

Credit: Julie Steinberg/ University of Delaware

Microplastics — small pieces of plastic less than five millimeters long — are an emerging marine pollution issue with implications for the health of the ocean and aquatic species.

Through funding from Delaware Sea Grant (DESG), University of Delaware master's student Julie Steinberg has been working with DESG-funded scientist Jonathan Cohen, assistant professor in the School of Marine Science and Policy, to understand the distribution and concentration of microplastics in the Delaware Bay.

The researchers collected water samples from August to December 2016 at five pre-selected stations along the Delaware Bay off Cherry Island Landfill in Wilmington, Delaware; Bombay Hook, Bowers and Broadkill beaches in central and southern Delaware; and in Cape May, New Jersey.

Steinberg used a density separator to extract the microplastics from the water samples, then analyzed the materials under a microscope.

"As you work, you remove a lot of different fibers and tiny plastics, most are invisible to the naked eye," she said.

Early results indicate a higher concentration of microplastics in industrial areas near the bay, the majority of which are filaments. The scientists found higher concentrations of smaller microplastics (0.3-1 mm) at Cherry Island and Bombay Hook, but found that microplastics at Cherry Island were three times more likely to be 1-5mm in size versus the smaller 0.3-1 mm size.

Study results will inform project partners at the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) who are developing a strategy to investigate the extent and implications of microplastics in the Delaware Bay, as well as state water quality regulators concerned about the potential impact for fisheries, including oysters.

Marine organisms like fish that rely on zooplankton as a nutrient can mistake marine plastics for food. Zooplankton also can ingest microplastics, raising important questions about biomagnification, the idea that microplastics can work their way up the food chain when zooplankton ingest microplastics, fish feed on zooplankton and humans consume fish.

"The impacts on human health are not fully studied or known," Steinberg said.

There are environmental consequences too. Animals can ingest or become entangled in larger scale macroplastics. Plastic particles that are not ingested can degrade as they weather, potentially releasing toxic chemicals into the marine environment. They also can concentrate contaminants such as organic pollutants and metals, and serve as vectors for these contaminants throughout the food web.

Of particular concern are microbeads, miniscule particles from 5 micrometers (less than the width of a human hair) to 1 millimeter in size. This summer, the scientists will conduct a bay-wide survey and create a standard protocol for the sampling and identification of microplastics (50 μm – 5mm) in water and beach sediments.

Steinberg specifically is interested in understanding the role of policy in marine debris management in places where waterways are a shared resource between states like the Delaware Bay, which is shared among Delaware, Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

###

About Delaware Sea Grant

The University of Delaware was designated as the nation's ninth Sea Grant College in 1976 to promote the wise use, conservation and management of marine and coastal resources through high-quality research, education and outreach activities that serve the public and the environment. UD's College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment administers the program, which conducts research in priority areas ranging from aquaculture to coastal hazards.

Media Contact

Peter Bothum

[email protected]

302-831-1418

@UDResearch

http://www.udel.edu

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag