The annual killifish lives in regions with extreme drought. A research group at the University of Basel now reports in “Science” that the early embryogenesis of killifish diverges from that of other species. Unlike other fish, their body structure is not predetermined from the outset. This could enable the species to survive dry periods unscathed.

Credit: Biozentrum, University of Basel

The annual killifish lives in regions with extreme drought. A research group at the University of Basel now reports in “Science” that the early embryogenesis of killifish diverges from that of other species. Unlike other fish, their body structure is not predetermined from the outset. This could enable the species to survive dry periods unscathed.

The turquoise killifish inhabits areas characterized by extreme conditions. The species, native to Africa, can survive prolonged periods of drought due to its unique life cycle. During humid periods, they lay their fertilized eggs in the mud. When the waters dry out, the adult fish die, while the embryos remain dormant in the dry mud by entering diapause. Once the rain falls, the embryo’s development continues.

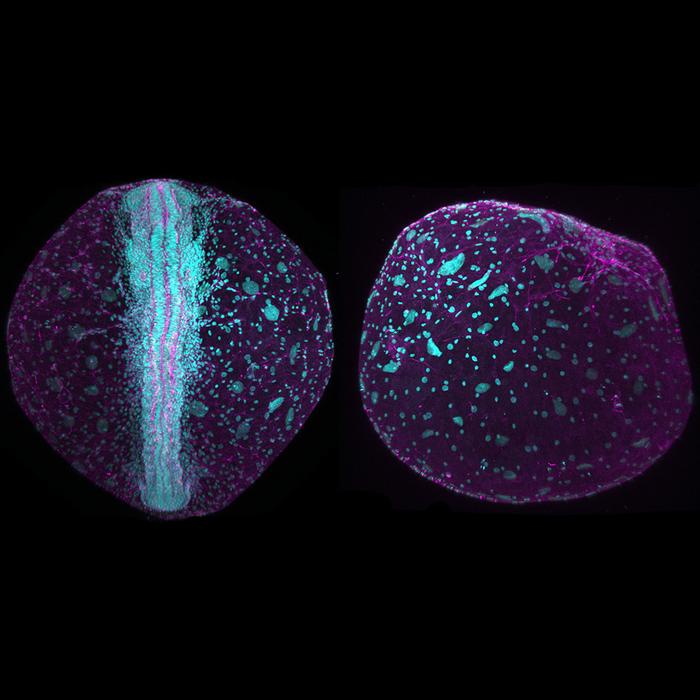

In contrast to other animals, the early embryos of killifish completely disperse into individual cells, which later aggregate to form the body axes and the embryo proper. The killifish species Nothobranchius furzeri has thus adapted its embryogenesis and life cycle to its environmental conditions.

Dorsal-ventral body axis

Prof. Alex Schier’s team at the Biozentrum, University of Basel, and researchers from Harvard University and the University of Washington in Seattle have discovered that killifish early embryogenesis differs from other fish species also at the molecular level. “Normally, the dorsal-ventral body axis, i.e. the back and the belly of the fish embryo, is already determined by the mother,” says Schier. “We have discovered that embryonic cells of killifish are not maternally pre-patterned, but self-organize to form the body axis.” In their recent publication in “Science”, the researchers describe how the dorsal-ventral axis is formed in killifish.

The so-called Huluwa factor plays a decisive role in early embryonic development in fish. It is passed on from the mother to the embryo and dictates the dorsal-ventral body axis. This is crucial for morphogenesis as well as the correct formation and positioning of organs.

“Previously, it was assumed that Huluwa is indispensable for axis formation,” explains Schier. “We have now been able to show that this factor is inactive in killifish. The embryonic cells find the right place on their own, they completely self-organize after dissociation.” In contrast to other fish, the determination of the dorsal-ventral axis in killifish occurs at a later stage and is regulated by embryonic factors. “The embryo emerges almost magically,” says Schier. “How exactly this happens still remains unclear.”

Well adapted to extreme environmental conditions

“Among fish, annual killifish have an atypical embryonic development that challenges the current concepts of axis formation,” says Schier. The absence of maternal pre-patterning in killifish embryos may offer a survival advantage, preventing the accumulation of damaged cells during dry seasons or the loss of body structure information. “Our study shows that evolution finds alternative developmental routes under selective pressures imposed by extreme environments,” concludes Schier.

Journal

Science

DOI

10.1126/science.ado7604

Article Title

Axis formation in annual killifish: Nodal and β-catenin regulate morphogenesis without Huluwa prepatterning

Article Publication Date

7-Jun-2024