Scientists have long deemed the ability to recognize faces innate for people and other primates — something our brains just know how to do immediately from birth. However, the findings of a new Harvard Medical School study published Sept. 4 in the journal Nature Neuroscience cast doubt on this longstanding view.

Working with macaques temporarily deprived of seeing faces while growing up, a Harvard Medical School team led by neurobiologists Margaret Livingstone, Michael Arcaro, and Peter Schade has found that regions of the brain that are key to facial recognition form only through experience and are absent in primates who don’t encounter faces while growing up.

The finding, the researchers say, sheds light on a range of neuro-developmental conditions, including those in which people can’t distinguish between different faces or autism, marked by aversion to looking at faces. Most importantly, however, the study underscores the critical formative role of early experiences on normal sensory and cognitive development, the scientists say.

Livingstone, the Takeda Professor of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School, explains that macaques — a close evolutionary relative to humans, and a model system for studying human brain development — form clusters of neurons responsible for recognizing faces in an area of the brain called the superior temporal sulcus by 200 days of age. The relative location of these brain regions, or patches, are similar across primate species.

That knowledge, combined with the fact that infants seem to preferentially track faces early in development, led to the longstanding belief that facial recognition must be inborn, she said. However, both humans and primates also develop areas in the brain that respond to visual stimuli they haven’t encountered for as long during evolution, including buildings and text. The latter observation puts a serious wrench in the theory that facial recognition is inborn.

To better understand the basis for facial recognition, Livingstone, along with postdoctoral fellow Arcaro and research assistant Schade, raised two groups of macaques. The first one, the control group, had a typical upbringing, spending time in early infancy with their mothers and then with other juvenile macaques, as well as with human handlers. The other group grew up raised by humans who bottle-fed them, played with and cuddled them — all while the humans wore welding masks. For the first year of their lives, the macaques never saw a face — human or otherwise. At the end of the trial, all macaques were put in social groups with fellow macaques and allowed to see both human and primate faces.

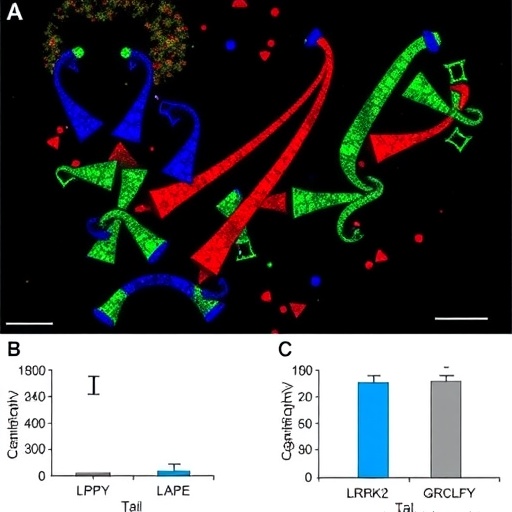

When both groups of macaques were 200 days old, the researchers used functional MRI to look at brain images measuring the presence of facial recognition patches and other specialized areas, such as those responsible for recognizing hands, objects, scenes and bodies.

The macaques who had typical upbringing had consistent “recognition” areas in their brains for each of these categories. Those who’d grown up never seeing faces had developed areas of the brain associated with all categories except faces.

Next, the researchers showed both groups images of humans or primates. As expected, the control group preferentially gazed at the faces in those images. In contrast, the macaques raised without facial exposure looked preferentially at the hands. The hand domain in their brains, Livingstone said, was disproportionally large compared to the other domains.

The findings suggest that sensory deprivation has a selective effect on the way the brain wires itself. The brain seems to become very good at recognizing things that an individual sees often, Livingstone said, and poor at recognizing things that it never or rarely sees.

“What you look at is what you end up ‘installing’ in the brain’s machinery to be able to recognize,” she added.

Normal development of these brain regions could be key to explaining a wide variety of disorders, the researchers said. One such disorder is developmental prosopagnosia–a condition in which people are born with the inability to recognize familiar faces, even their own, due to the failure of the brain’s facial recognition machinery to develop properly. Likewise, Livingstone said, some of the social deficits that develop in people with autism spectrum disorders may be a side effect stemming from the lack of experiences that involve looking at faces, which children with these disorders tend to avoid. The findings suggest that interventions to encourage early exposure to faces may assuage the social deficits that stem from lack of such experiences during early development, the team said.

###

Co-investigators on the research included Justin Vincent and Carlos Ponce, of Harvard Medical School.

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 EY 25670, RO1 EY 16187, F32 EU 24187 and P30 EU 12196, and a William Randolph Hearst Fellowship. This research was carried out in part at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at the Massachusetts General Hospital, using resources provided by the Center for Functional Neuroimaging Technologies, P41EB015896, a P41 Biotechnology Resource Grant supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, National Institutes of Health, and NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant S10RR021110.

Media Contact

Ekaterina Pesheva

[email protected]

617-432-0441

@HarvardMed

http://hms.harvard.edu