Noble gases have a reputation for being unreactive, inert elements, but more than 60 years ago Neil Bartlett demonstrated the first way to bond xenon. He created XePtF6, an orange-yellow solid. Because it’s difficult to grow sufficiently large crystals that contain noble gases, some of their structures — and therefore functions — remain elusive. Now, researchers have successfully examined tiny crystallites of noble gas compounds. They report structures of multiple xenon compounds in ACS Central Science.

Noble gases have a reputation for being unreactive, inert elements, but more than 60 years ago Neil Bartlett demonstrated the first way to bond xenon. He created XePtF6, an orange-yellow solid. Because it’s difficult to grow sufficiently large crystals that contain noble gases, some of their structures — and therefore functions — remain elusive. Now, researchers have successfully examined tiny crystallites of noble gas compounds. They report structures of multiple xenon compounds in ACS Central Science.

Since Bartlett’s discovery, which is commemorated with an International Historic Chemical Landmark, hundreds of noble gas compounds have been synthesized, and some crystal structures have been characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. However, noble gas-containing crystals are typically sensitive to moisture in air. This chemical property makes them highly reactive and challenging to handle, requiring special techniques and equipment to grow crystals large enough for X-ray diffraction analysis. Therefore, detailed structures of that first xenon compound and several other noble gas-containing compounds have eluded researchers. Recently, another technique — 3D electron diffraction — has revealed the structures of small nanoscale crystals. These crystallites are stable in air, but the technique hasn’t been widely applied to air-sensitive compounds. So, Lukáš Palatinus, Matic Lozinšek and colleagues wanted to test 3D electron diffraction on crystallites of xenon-containing compounds.

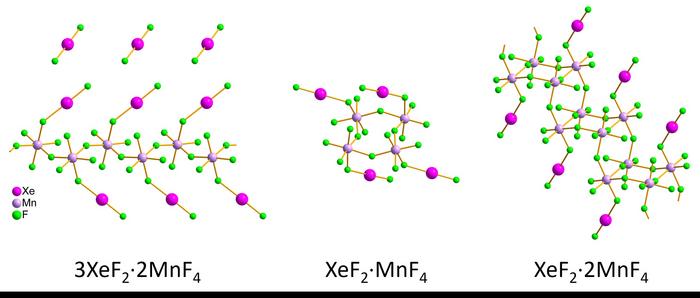

The researchers synthesized three xenon difluoride–manganese tetrafluoride compounds, obtaining individual red crystals and pink crystalline powders. Samples were kept stable by first cooling a holder with liquid nitrogen, adding the sample and then covering the filled holder with multiple protective layers during the transfer into a transmission electron microscope. The team measured the xenon-fluoride (Xe–F) and manganese-fluoride (Mn–F) bond lengths and angles for nanometer-sized crystallites in the pink crystalline powder using 3D electron diffraction. Then the structures were compared to results the team obtained on the larger, micrometer-sized wine-red crystals by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. The two methods were in good agreement, despite small differences, according to the researchers, and the results showed that the structures were:

- Infinite zig zag chains for 3XeF2·2MnF4.

- Rings for XeF2·MnF4.

- Staircase-like double chains for XeF2·2MnF4.

As a result of this successful demonstration of 3D electron diffraction on xenon compounds, the researchers say the technique could be used to discover the structures of XePtF6 and other challenging noble gas compounds that have evaded characterization for decades, as well as other air-sensitive substances.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Czech Science Foundation and Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency joint project within the Central European Science Partnership, the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, the Jožef Stefan Institute Director’s Fund, and the CzechNanoLab Research Infrastructure supported by Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic.

The paper’s abstract will be available on Aug. 14 at 8 a.m. Eastern time here: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acscentsci.4c00815

For more of the latest research news, register for our upcoming meeting, ACS Fall 2024. Journalists and public information officers are encouraged to apply for complimentary press registration by completing this form.

###

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

Registered journalists can subscribe to the ACS journalist news portal on EurekAlert! to access embargoed and public science press releases. For media inquiries, contact [email protected].

Note: ACS does not conduct research, but publishes and publicizes peer-reviewed scientific studies.

Follow us: X, formerly Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram

Journal

ACS Central Science

DOI

10.1021/acscentsci.4c00815

Article Title

“Reactive Noble-Gas Compounds Explored by 3D Electron Diffraction: XeF2−MnF4 Adducts and a Facile Sample Handling Procedure”

Article Publication Date

14-Aug-2024