Credit: University of Pennsylvania

A new study led by University of Pennsylvania researchers has found that the oral microbiome is affected by diabetes, causing a shift to increase its pathogenicity. The research, published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe this week, not only showed that the oral microbiome of mice with diabetes shifted but that the change was associated with increased inflammation and bone loss.

"Up until now, there had been no concrete evidence that diabetes affects the oral microbiome," said Dana Graves, senior author on the new study and vice dean of scholarship and research at Penn's School of Dental Medicine. "But the studies that had been done were not rigorous."

Just four years ago, the European Federation of Periodontology and the American Academy of Periodontology issued a report stating there is no compelling evidence that diabetes is directly linked to changes in the oral microbiome. But Graves and colleagues were skeptical and decided to pursue the question, using a mouse model that mimics Type 2 diabetes.

"My argument was that the appropriate studies just hadn't been done, so I decided, We'll do the appropriate study," Graves said.

Graves co-authored the study with Kyle Bittinger of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, who assisted with microbiome analysis, along with E Xiao from Peking University, who was the first author, and co-authors from the University of São Paulo, Sichuan University, the Federal University of Minas Gerais and the University of Capinas. The authors consulted with Daniel Beiting of Penn Vet's Center for Host-Microbial Interactions and did the bone-loss measurements at the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Diseases.

The researchers began by characterizing the oral microbiome of diabetic mice compared to healthy mice. They found that the diabetic mice had a similar oral microbiome to their healthy counterparts when they were sampled prior to developing high blood sugar levels, or hyperglycemia. But, once the diabetic mice were hyperglycemic, their microbiome became distinct from their normal littermates, with a less diverse community of bacteria.

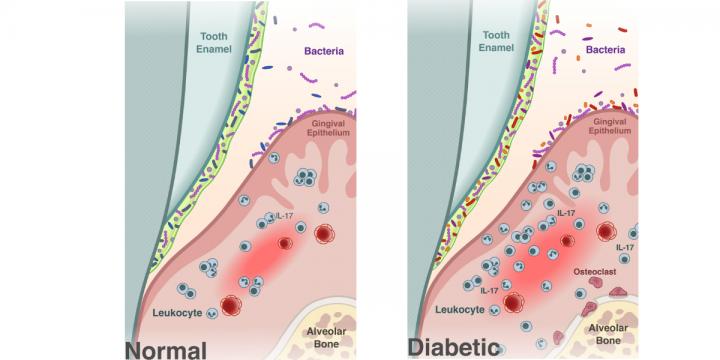

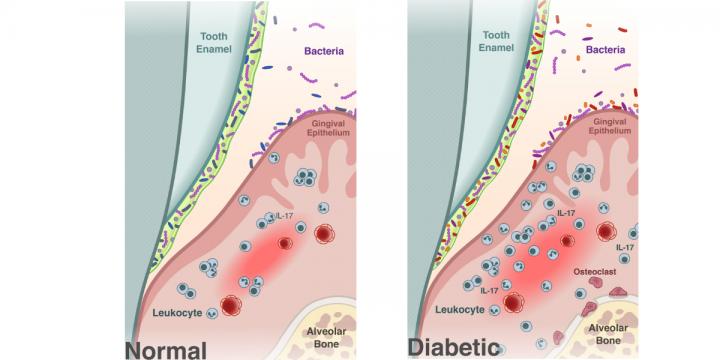

The diabetic mice also had periodontitis, including a loss of bone supporting the teeth, and increased levels of IL-17, a signaling molecule important in immune response and inflammation. Increased levels of IL-17 in humans are associated with periodontal disease.

"The diabetic mice behaved similar to humans that had periodontal bone loss and increased IL-17 caused by a genetic disease," Graves said.

The findings underscored an association between changes in the oral microbiome and periodontitis but didn't prove that the microbial changes were responsible for disease. To drill in on the connection, the researchers transferred microorganisms from the diabetic mice to normal germ-free mice, animals that have been raised without being exposed to any microbes.

These recipient mice also developed bone loss. A micro-CT scan revealed they had 42 percent less bone than mice that had received a microbial transfer from normal mice. Markers of inflammation also went up in the recipients of the diabetic oral microbiome.

"We were able to induce the rapid bone loss characteristic of the diabetic group into a normal group of animals simply by transferring the oral microbiome," said Graves.

With the microbiome now implicated in causing the periodontitis, Graves and colleagues wanted to know how. Suspecting that inflammatory cytokines, and specifically IL-17, played a role, the researchers repeated the microbiome transfer experiments, this time injecting the diabetic donors with an anti-IL-17 antibody prior to the transfer. Mice that received microbiomes from the treated diabetic mice had much less severe bone loss compared to mice that received a microbiome transfer from untreated mice.

The findings "demonstrate unequivocally" that diabetes-induced changes in the oral microbiome drive inflammatory changes that enhance bone loss in periodontitis, the authors wrote.

Though IL-17 treatment was effective at reducing bone loss in the mice, it is unlikely to be a reasonable therapeutic strategy in humans due to its key role in immune protection. But Graves noted that the study highlights the importance for people with diabetes of controlling blood sugar and practicing good oral hygiene.

"Diabetes is one of the systemic disease that is most closely linked to periodontal disease, but the risk is substantially ameliorated by good glycemic control," he said. "And good oral hygiene can take the risk even further down."

###

In addition to Graves and Bittinger, co-authors included E Xiao, Marcelo Mattas, Shanshan Chen and Yingying Wu of Penn Dental Medicine; Gustavo Henrique Apolinário Vieira of the University of São Paulo; Joice Dias Correa of the Federal University of Minas Gerais; and Mayra Laino Albieiro of the University of Campinas.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (DE017732 and DE021921) with assistance from Penn Vet's Center for Host-Microbioal Interactions and the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders.

Media Contact

Katherine Unger Baillie

[email protected]

215-898-9194

@Penn

http://www.upenn.edu/pennnews

Original Source

https://news.upenn.edu/news/diabetes-causes-shift-oral-microbiome-fosters-periodontitis-penn-study-finds http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2017.06.014