For the first cell to develop into an entire organism, genes, RNA molecules and proteins have to work together in a complex way. At first, this process is indirectly controlled by the mother. At a certain point in time, the protein GRIF-1 ensures that the offspring cut themselves off from this influence and start their own course of development. A research team from Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) details how this process works in the journal Science Advances.

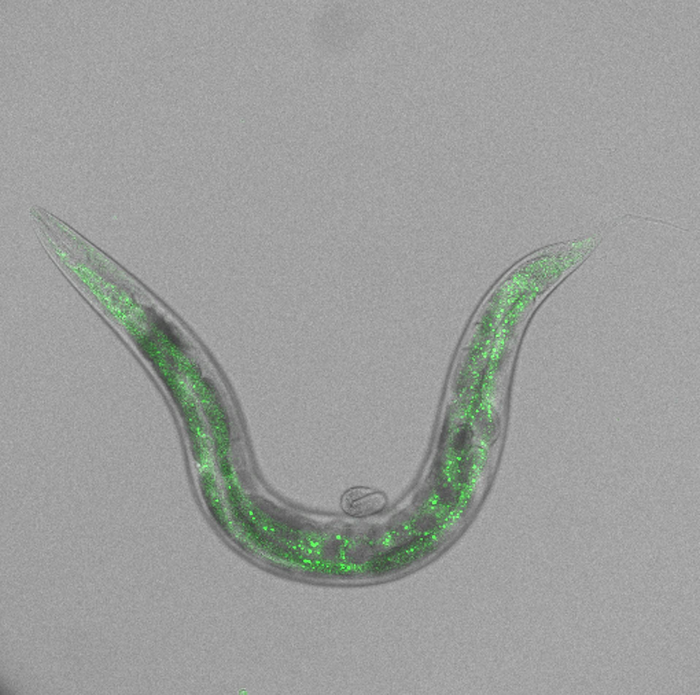

Credit: Uni Halle / AG Christian Eckmann

For the first cell to develop into an entire organism, genes, RNA molecules and proteins have to work together in a complex way. At first, this process is indirectly controlled by the mother. At a certain point in time, the protein GRIF-1 ensures that the offspring cut themselves off from this influence and start their own course of development. A research team from Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) details how this process works in the journal Science Advances.

When a new organism starts to develop, the mother calls the shots. During fertilisation, the egg cell and sperm fuse to form a single new cell. However, the course of cell division, and thus how a new living being forms, is initially determined by the mother cell. “Regardless of the organism, cell division is initially pre-programmed by the mother,” explains geneticist Professor Christian Eckmann from MLU. The mother’s cell provides a developmental starter set that includes the first proteins as well as the RNA molecules that serve as blueprints for further proteins. All this is necessary to jump start cell division and an organism’s development.

During this initial period, cells have no access to its own genetic material, something which restricts its own development. “As important as this maternal contribution is for the new organism, at a certain point these components have to be removed. Only then can it fully utilise its own genetic material and pursue its own course of development,” says Eckmann. This process starts much later in germ cells, the precursors to gametes, than in somatic cells, which develop into all of the body’s other cells. “Cells have a lot of options for killing things off. Longevity has to be earned,” says Eckmann. In germ cell precursors, so called poly-A polymerases provide the mother’s short-lived RNA molecules a kind of protective cap to ensure they live longer.

In experiments with the model organism C. elegans, Eckmann’s team discovered how the cord cutting process works at a molecular level in germ cells. At a certain stage, cells start producing the protein GRIF-1. The instructions for this process come from the maternal RNA. As soon as the protein is built, it starts looking for the maternal poly-A polymerases, binds to them, and attaches to them a kind of marker. “It’s like a flag which GRIF-1 uses to mark which maternal proteins are to be degraded,” says Eckmann. This sets off a chain reaction: once the poly-A polymerases are destroyed, they can no longer attach new protective caps to maternal RNA molecules, which would protect them from degradation and thus, no new maternal proteins can be built. “Eventually, all maternal RNA molecules and proteins are eliminated. The germ cell gains full access to its genetic material and can continue to develop on its own,” concludes Eckmann. It remains unclear how the cell knows that it has to produce GRIF-1 and that it has to activate its own genetic material.

Incidentally, this long maternal control process is there for a reason: the genetic material in the germ cells is passed on to the offspring via the sperm or egg. Therefore, it must be preserved as completely and as error-free as possible. Eckmann’s researchers artificially prevented this degradation process from happening in the laboratory in C. elegans. “A disruption to this process causes a lot problems. The germline cannot develop robustly and the worms’ offspring become more infertile with each generation,” says Eckmann.

The work was supported by the German Research Foundation within the framework of the Research Training Group “GRK 2467: Intrinsically disordered proteins – Molecular principles, cellular functions and diseases”.

Study: Oyewale T.D., Eckmann C.R. Germline immortality relies on TRIM32-mediated turnover of a maternal mRNA activator in C. elegans. Science Advances (2022). doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abn0897

Journal

Science Advances

DOI

10.1126/sciadv.abn0897

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Animals

Article Title

Germline immortality relies on TRIM32-mediated turnover of a maternal mRNA activator in C. elegans

Article Publication Date

14-Oct-2022

COI Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.