CHICAGO, Aug. 23, 2022 — Large pieces of plastic can break down into nanosized particles that often find their way into the soil and water. Perhaps less well known is that they can also float in the air. It’s unclear how nanoplastics impact human health, but animal studies suggest they’re potentially harmful. As a step toward better understanding the prevalence of airborne nanoplastics, researchers have developed a sensor that detects these particles and determines the types, amounts and sizes of the plastics using colorful carbon dot films.

Credit: Nitzan Shauloff

CHICAGO, Aug. 23, 2022 — Large pieces of plastic can break down into nanosized particles that often find their way into the soil and water. Perhaps less well known is that they can also float in the air. It’s unclear how nanoplastics impact human health, but animal studies suggest they’re potentially harmful. As a step toward better understanding the prevalence of airborne nanoplastics, researchers have developed a sensor that detects these particles and determines the types, amounts and sizes of the plastics using colorful carbon dot films.

The researchers will present their results today at the fall meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS Fall 2022 is a hybrid meeting being held virtually and in-person Aug. 21–25, with on-demand access available Aug. 26–Sept. 9. The meeting features nearly 11,000 presentations on a wide range of science topics.

“Nanoplastics are a major concern if they’re in the air that you breathe, getting into your lungs and potentially causing health problems,” says Raz Jelinek, Ph.D., the project’s principal investigator. “A simple, inexpensive detector like ours could have huge implications, and someday alert people to the presence of nanoplastics in the air, allowing them to take action.”

Millions of tons of plastic are produced and thrown away each year. Some plastic materials slowly erode while they’re being used or after being disposed of, polluting the surrounding environment with micro- and nanosized particles. Nanoplastics are so small — generally less than 1-µm wide — and light that they can even float in the air, where people can then unknowingly breathe them in. Animal studies suggest that ingesting and inhaling these nanoparticles may have damaging effects. Therefore, it could be helpful to know the levels of airborne nanoplastic pollution in the environment.

Previously, Jelinek’s research team at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev developed an electronic nose or “e-nose” for monitoring the presence of bacteria by adsorbing and sensing the unique combination of gas vapor molecules that they release. The researchers wanted to see if this same carbon-dot-based technology could be adapted to create a sensitive nanoplastic sensor for continuous environmental monitoring.

Carbon dots are formed when a starting material that contains lots of carbon, such as sugar or other organic matter, is heated at a moderate temperature for several hours, says Jelinek. This process can even be done using a conventional microwave. During heating, the carbon-containing material develops into colorful, and often fluorescent, nanometer-size particles called “carbon dots.” And by changing the starting material, the carbon dots can have different surface properties that can attract various molecules.

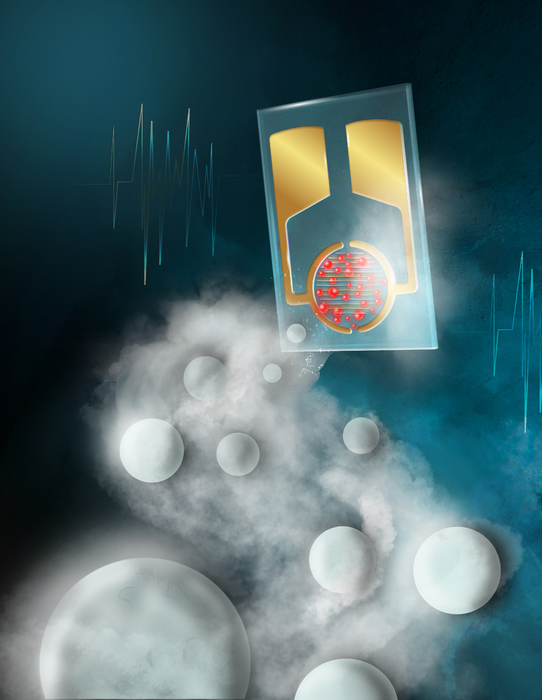

To create the bacterial e-nose, the team spread thin layers of different carbon dots onto tiny electrodes, each the size of a fingernail. They used interdigitated electrodes, which have two sides with interspersed comb-like structures. Between the two sides, an electric field develops, and the stored charge is called capacitance. “When something happens to the carbon dots — either they adsorb gas molecules or nanoplastic pieces — then there is a change of capacitance, which we can easily measure,” says Jelinek.

Then the researchers tested a proof-of-concept sensor for nanoplastics in the air, choosing carbon dots that would adsorb common types of plastic — polystyrene, polypropylene and poly(methyl methacrylate). In experiments, nanoscale plastic particles were aerosolized, making them float in the air. And when electrodes coated with carbon-dot films were exposed to the airborne nanoplastics, the team observed signals that were different for each type of material, says Jelinek. Because the number of nanoplastics in the air affects the intensity of the signal generated, Jelinek adds that currently, the sensor can report the amount of particles from a certain plastic type either above or below a predetermined concentration threshold. Additionally, when polystyrene particles in three sizes — 100-nm wide, 200-nm wide and 300-nm wide — were aerosolized, the sensor’s signal intensity was directly related to the particles’ size.

The team’s next step is to see if their system can distinguish the types of plastic in mixtures of nanoparticles. Just as the combination of carbon dot films in the bacterial e-nose distinguished between gases with differing polarities, Jelinek says it’s likely that they could tweak the nanoplastic sensor to differentiate between additional types and sizes of nanoplastics. The capability to detect different plastics based on their surface properties would make nanoplastic sensors useful for tracking these particles in schools, office buildings, homes and outdoors, he says.

The researchers acknowledge support from the Israel Innovation Authority.

A recorded media briefing on this topic will be posted Tuesday, Aug. 23, by 10 a.m. Eastern time at www.acs.org/acsfall2022briefings.

ACS Fall 2022 will be a vaccination-required and mask-recommended event for all attendees, exhibitors, vendors and ACS staff who plan to participate in-person in Chicago. For detailed information about the requirement and all ACS safety measures, please visit the ACS website.

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS’ mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and all its people. The Society is a global leader in promoting excellence in science education and providing access to chemistry-related information and research through its multiple research solutions, peer-reviewed journals, scientific conferences, eBooks and weekly news periodical Chemical & Engineering News. ACS journals are among the most cited, most trusted and most read within the scientific literature; however, ACS itself does not conduct chemical research. As a leader in scientific information solutions, its CAS division partners with global innovators to accelerate breakthroughs by curating, connecting and analyzing the world’s scientific knowledge. ACS’ main offices are in Washington, D.C., and Columbus, Ohio.

To automatically receive press releases from the American Chemical Society, contact [email protected].

Note to journalists: Please report that this research was presented at a meeting of the American Chemical Society.

Follow us: Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram

Title

Carbon dots for environmental applications

Abstract

Carbon dots (Cdots) exhibit remarkable physico-chemical properties, and have been employed in diverse optical, electronic, and biological applications. In this presentation I will present some of our recent studies in which we demonstrated interesting environmentally oriented applications of Cdot systems. Specifically, I will present an artificial nose for sensing and distinguishing vapor molecules, based upon recording the capacitance of interdigitated electrodes (IDEs) coated with Cdots exhibiting different polarities. The capacitive C-dot-IDE sensor was employed to continuously monitor microbial proliferation, discriminating among bacteria through detection of distinctive “volatile compound fingerprint” for each bacterial species. Different research projects I will discuss have focused on the construction of Cdot-hydrogel composites for sunlight-mediated water purification and oil-spill cleaning. These applications are based upon exploiting the photothermal properties of the Cdots.